Caption

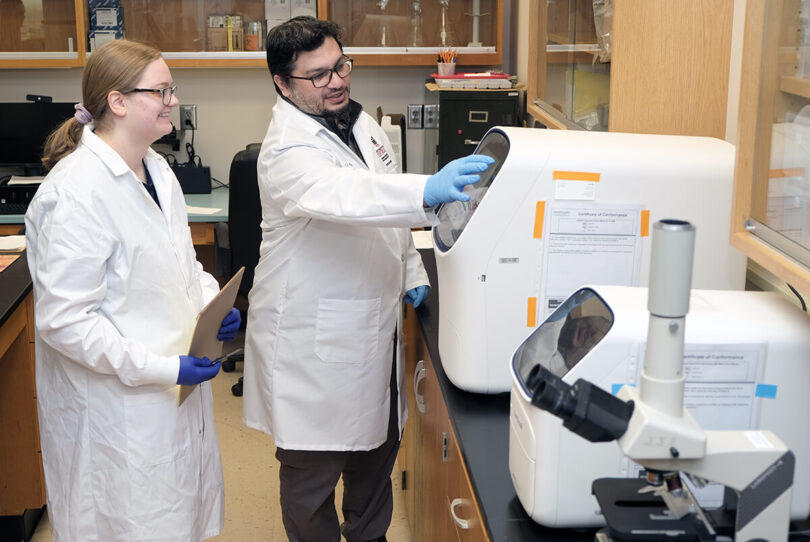

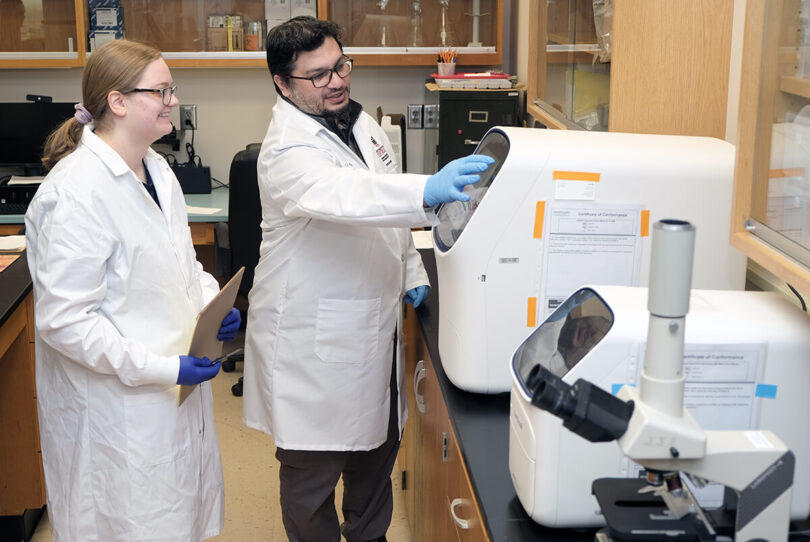

UGA researcher Issmat Kassem, pictured to the right of research professional Miranda Barr, has discovered a gene that causes bacteria to be resistant to antibiotics in Georgia sewer water.

Credit: Contributed

Recently, a gene that makes bacteria resistant to one of the world’s strongest antibiotics were found in an unnamed urban sewer system in Georgia, and that has researchers at the University of Georgia worried. GPB’s Ellen Eldridge explains why.

UGA researcher Issmat Kassem, pictured to the right of research professional Miranda Barr, has discovered a gene that causes bacteria to be resistant to antibiotics in Georgia sewer water.

The emergence and spread of mobile colistin resistance (MCR) genes jeopardize the efficacy of an antibiotic which is a last resort for treating deadly infections — and MCR-9 was recently found in sewer water tested by researchers at the University of Georgia.

The first MCR gene was found in 2016, and 10 MCR genes have been identified along with variants, said lead researcher Issmat Kassem, an associate professor with UGA's College of Agricultural and Environmental Science.

Antimicrobial resistance, which the World Health Organization declared “one of the top 10 global public health threats facing humanity,” occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and no longer respond to medicines.

The presence of MCR in Georgia, that it was found inside a bacterium that is often overlooked, and that it occurred even without the use of colistin in U.S. agriculture, is a serious problem that requires immediate action on the part of many industries including research, health care and government institutions to work together toward a solution, Kassem said.

His research focuses on MCR’s presence around the world, and the team was surprised at how quickly they detected MCR — they found evidence of the gene in the first sample they took.

Kassem said that demonstrates that the gene is becoming established in the U.S.

"Colistin historically or currently has been used to treat multi-drug infections," Kassem said. "So, basically, those are infections that are resistant to other antibiotics. When those antibiotics fail to treat this infection or certain infections, we resort to the use of of colistin."

Health care workers have been seeing multi-drug resistant infections that are extremely difficult to treat and are, sometimes, untreatable, Kassem said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that there are more than 2.8 million infections in the states with an antibiotic-resistant bacterium.

More than 35,000 people die each year from these infections, and those are estimates, Kassem said. Projected globally, an estimated 750,000 people would lose their lives to resistant infections.

As far as what individuals can do, Kassem said to stay cautious about using antibiotics and make sure to take all antibiotics as prescribed.

"We cannot just pop two pills and then [say], 'OK, we're feeling better' and forget about the rest of the prescription," Kassem said. "We can't just take those pills and dump them, flush them down the toilet or give them to someone else."

Patients shouldn't be pushing their doctors to prescribe antibiotics, and medical doctors shouldn't readily prescribe antibiotics. There should be a conversation, he said.

Kassem declined to name the location of the testing but says this gene is carried by bacteria on travelers and on imported food, meaning MCR-9 is likely more widespread than previously thought.