Caption

African Americans register to vote in the July 4 Georgia Democratic Primary in Atlanta on May 3, 1944.

Credit: The Associated Press

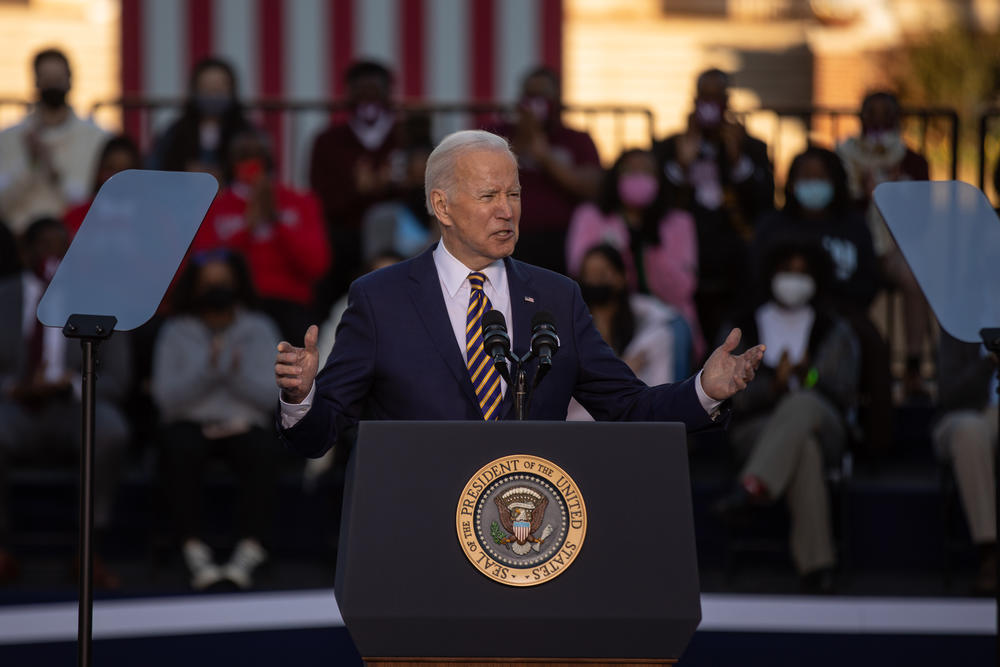

Last week, President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris came to Georgia to deliver speeches calling on Congress to take action to pass a pair of sweeping voting bills.

"Today, we come to Atlanta — the cradle of civil rights — to make clear what must come after that dreadful day when a dagger was literally held at the throat of American democracy," Biden said.

But his words were not universally well received — even by some voting rights groups that also want federal action. And the fate of the legislation seems to be D.O.A. because of two Democrats’ unwillingness to change Senate rules — and a governing margin too narrow to have any holdouts.

Republicans like Gov. Brian Kemp used the trip to attack Democrats’ flailing federal agenda and dig in on their stance on elections.

“Georgia is ground zero for the Biden-Harris assault on election integrity," Kemp said before the president's speech. "We have secured the ballot box, restored confidence in our elections and made it easy to vote and hard to cheat.”

This week, we look at the long-shot push for federal voting overhauls and what that means for politics in Georgia.

Since Reconstruction, Georgia has been a prominent state in the ongoing debates and fights over who gets to vote in America.

In the last season of Battleground: Ballot Box, we talked to Morehouse College professor Adrienne Jones about some of the backlash that came from the 15th Amendment giving Black men the right to vote.

"We slowly but quickly make our way towards Jim Crow laws," she said. "And those laws are preventing Black people, particularly in the former Confederate states, from taking full advantage of their liberties and in particular, being able to access the polls."

She told us about Georgia’s early constitutions that forbade Black people from voting all the way up through the 1900s, including poll taxes, grandfather clauses, literacy tests and more.

"The United States is actually the only country where they have granted the franchise to groups of people and then taken it back again," she said.

African Americans register to vote in the July 4 Georgia Democratic Primary in Atlanta on May 3, 1944.

But in 1957, the federal government enacted the Civil Rights Act, which created some ways for the Justice Department to tackle civil and voting rights for Black citizens, including the launch of the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department.

Now, this was no slam dunk. The main opponents were Southern Democrats, including all of Georgia’s 10 representatives. In the Senate, the bill was watered down by Majority Leader (and future president) Lyndon B. Johnson to get support from liberals in the Northwest. Ultimately, the Senate agreed to the bill with 18 “No” votes from Democrats, including Georgia’s segregationist Sens. Richard B. Russell and Herman Talmadge.

While that earlier Civil Rights Act was considered “toothless,” it opened the door for other legislation down the road.

Now to see the connection to our modern debate over voting rights, you have to fast forward to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Most Americans had seen Birmingham, Alabama’s public safety department, helmed by Bull Connor, on television viciously attacking Black protestors with hoses, batons and dogs.

President John F. Kennedy called up the National Guard to integrate the University of Alabama and keep Black students safe. The early rumblings of what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964 began to take shape — again with bipartisan support and with Southern opposition.

On June 11, 1963, Kennedy delivered his Report to the American People on Civil Rights:

"It ought to be possible therefore for American students of any color to attend any public institution they select without having to be backed up by troops; it ought to be possible for American consumers of any color to receive equal service in places of public accommodation such as hotels and restaurants and theaters and retail stores without being forced to resort to demonstrations in the street; and it ought to be possible for American citizens of any color to register and to vote in a free election without interference or fear of reprisal," he said.

Civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated the next day.

Public support for legislation had grown in 1963, with the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and after the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing that killed four young Black girls. But Kennedy’s agenda was stalled by Southern lawmakers who were staunchly opposed — and not just on civil rights.

At his final press conference before being assassinated in Dallas, Kennedy was asked about the legislative gridlock and if the bill would pass.

"However dark it looks now, I think that 'Westward look the land is bright,' and I think by next summer it may be."

Lyndon Johnson, newly sworn in as president, pushed Congress to act. After passing the House, and overcoming a 54-day-long filibuster in the Senate led by Russell of Georgia, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law.

Another push more focused on voting rights came in 1965, after Georgia’s John Lewis and others were beaten while marching in Selma, Ala., in what became known as Bloody Sunday.

That law was passed with bipartisan support 328-74 in the House and passed the Senate 77-19 — again, with Southern Democrats opposed.

The sweeping law drastically overhauled civil and voting rights in America, targeting racial discrimination in the South and other jurisdictions. It outlawed literacy tests and ordered federal oversight that required the government to pre-clear voting changes in jurisdictions like Georgia with a history of racist laws.

The Civil Rights Act has been amended several times; 1970, 1975, 1982, 1992 and 2006 — all with bipartisan support — to address expirations of different provisions or tweak language to reflect the situations of the times.

But after the Supreme Court’s landmark 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision that essentially gutted most of the Act, the debate on what to do about federal voting rights has been bitterly partisan.

So when President Biden and Vice President Harris came to the Atlanta University Center last week to urge Congress to change the filibuster rule from a 60-vote threshold to allow the Democrats’ bare-minimum majority to pass equally sweeping voting rights legislation, it was a tough sell.

"Democrats, Republicans and independents worked to pass the historic Civil Rights Act and the voting rights legislation," Biden said. "And each successive generation continued that ongoing work."

But we live in a different political reality now.

President Joe Biden calls for the Senate to pass voting rights legislation during remarks at the Atlanta University Center on Jan. 11.

The two bills being considered, the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act and the Freedom to Vote Act, are wide-ranging legislation that would drastically overhaul elections across the country at a scale much larger than big voting bills passed locally by GOP-controlled states.

The Voting Rights Advancement Act would restore a lot of the Voting Rights Act that was overturned by Shelby vs. Holder, while the Freedom to Vote Act would create standards for federal elections that all states would have to follow, including redistricting and campaign finance reform, tackling attacks on election workers and more.

Republicans have called the measures a federal takeover of elections and are opposed, while others have said the bill seeks to do too much with too narrow a legislative majority.

Biden took an aggressive tone in his Georgia speech. He evoked some of the uglier figures in American history to compare opponents to these sweeping bills.

"So, I ask every elected official in America: How do you want to be remembered?," he asked. "At consequential moments in history, they present a choice: Do you want to be on the side of Dr. King or George Wallace? Do you want to be on the side of John Lewis or Bull Connor? Do you want to be on the side of Abraham Lincoln or Jefferson Davis?"

But Biden received pushback from voting rights groups who said coming to Georgia was unnecessary, too late, and should have been spent strong-arming lawmakers into voting for his agenda.

Over the Martin Luther King Jr. Day weekend, there was even more focus on federal voting rights, as groups marched, protested and urged Congress to act.

One of the more notable comments came from Yolanda Renee King, the granddaughter of Dr. King, who spoke about the need to pass voting rights ASAP.

"At just 13, I have fewer voting rights than I did the day that I was born," she said. "That's why my family has spent this Martin Luther King, Jr. weekend mobilizing: first in Phoenix and now in Washington to demand the president and Senate get voting rights legislation done. Our rights are on the line."

Two Democrats are in the drivers’ seats for what comes next: Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema is opposed to changing the filibuster rules, as is West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin.

The Senate is taking up the bills, and we’ll see if 2022’s climate, and the president’s urging, will be enough.

Battleground: Ballot Box is a production of Georgia Public Broadcasting. Our producer is Jess Mador, our editor is Wayne Drash. Our engineer is Jesse Nighswonger, who also wrote our theme music. You can subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts or anywhere you get podcasts. Thanks for listening.