Section Branding

Header Content

The Q100 bus to Rikers can be a lifeline for families with loved ones inside the jail

Primary Content

Came'e Lee sits alone on a fall day, waiting for the Q100, at a quiet New York City bus stop that seems all but forgotten on the edge of the East River. She's fidgety: she keeps checking her phone and looking around at the other people at the bus stop. A few days before, she got a call from Rikers Island Correctional Facility.

It was her son.

He's 20 years old. He had been at Rikers for around a month. He'd violated a protection order. There was no information regarding when he'd be released or get a trial. On the phone, he told her he was struggling. He also said he'd been beaten up. For his safety, NPR is withholding his name.

"He wanted me to know that if he doesn't make it, he did not kill himself," she says.

Lee's fears are not unfounded. Detainees, families and advocates report horrific conditions that include a lack of food, and medical attention. They also say a staffing shortage has meant gangs are now running the jail. Even city and state officials have said Rikers is at a breaking point.

Getting information about the wellbeing of detainees can be difficult. Speaking by phone to loved ones inside is also challenging. So many of their relatives say that it is difficult to even contact detainees to check on their wellbeing.

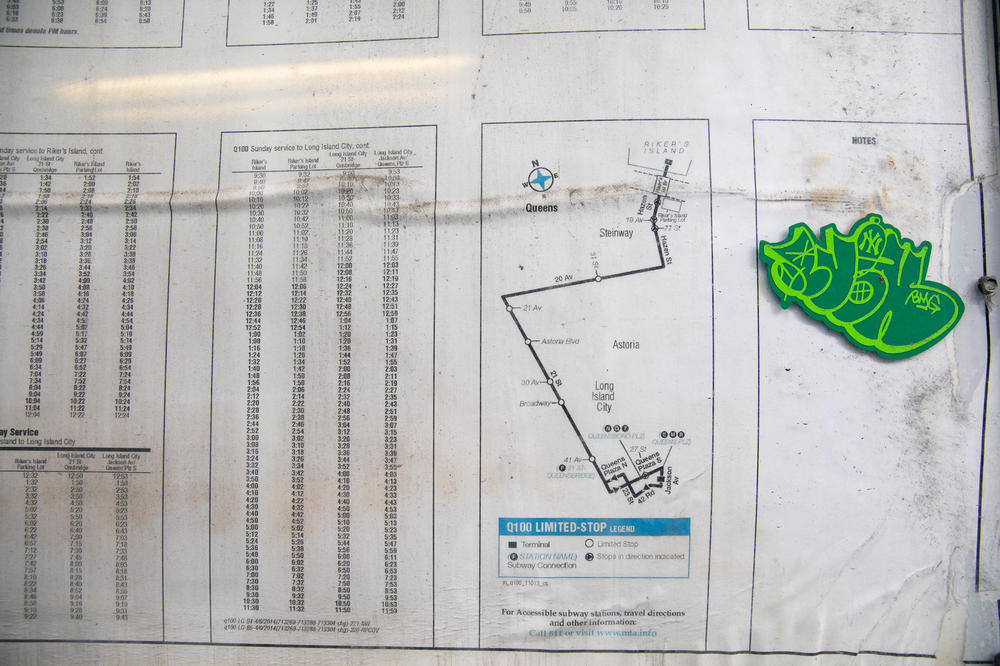

The Q100 is one of the most reliable ways to check in on a loved one on the island. It runs from Queens to Rikers Island. It is a lifeline; a way to stay in touch. NPR spent several weeks riding the bus, to and from the island, interviewing passengers. Among them, Came'e Lee, who says she's been consumed with thoughts about her son's wellbeing since she got that call.

"Every night, throughout the night," she says. "In the middle of the night. In the day. During the day. In the morning, during the morning. In the evening, during the evening. It's a feeling I can't ... I can't explain."

Q100 riders say they go see inmates in person when they can't get answers by phone

Here at the Q100 bus stop, it's nearly all women, mostly of color. The bus runs every 15 minutes or so; it's always half full.

Many are dressed up. Some women flaunt stunning electric blue hair, fluttering eyelashes, impeccable pastel purple nails, and velvety soft makeup. It's a mix of glamour and anxiety.

One woman named Francine says her brother almost died in Rikers. He was in for three months, she says, for violating a protection order. She asks that her last name not be used, to spare her brother the stigma of incarceration.

As she talks, she lights a cigarette and looks down the street, to see if the Q100 is coming. She says her brother had a broken leg at Rikers, that got infected. She says he couldn't get medical attention. "The nurse was busy, the doctor was busy. And he was sitting there, bleeding."

She says she'd call, and no one would give her answers.

"Devastating wasn't even the word," she says, "to hear my brother calling home, and crying, and saying 'I'm gonna lose my leg.'"

When he was released, she says she had to rush him to the ER. In the race to get him to a hospital, she says they left his belongings behind.

Now she's waiting for the bus, to go pick them up.

A woman named Toya is here with her 1-year-old son. They've come to see her husband. "They're not treating them like human beings, and that's really it," she says.

Her husband has been inside for a year, awaiting trial. She says, he hasn't received medical attention for breathing problems; she asked that her last name be withheld, out of concern for his safety.

"If you're looking for justice out of a person, treating them like they're an animal ain't gonna make it no better. Do you expect them to make better choices when they're angry?" she asks.

2021 was a deadly year at Rikers

A lot of these women say they are frustrated with the people they are coming to visit. Their incarceration has affected the entire family: moms, daughters, wives, girlfriends.

But they're also frustrated with how dangerous the jail has become. The Department of Correction says there were 14 deaths in custody in 2021. Two more men died shortly after being granted compassionate leave. Advocates say those deaths should be counted among the total. It's the deadliest year on the island since 2013. Several of those deaths were ruled suicides; there were also various drug overdoses. At least two were COVID-19 related.

Staff have raised the alarm over a surge in COVID-19 cases at the jail. At the end of December, in a public letter, then Commissioner of the New York Department of Correction, Vincent Schiraldi, talked about relatively low vaccination rates for detainees. He wrote, in part, "for the past several months our COVID positivity rate was consistently hovering at approximately 1%. Yesterday it was 9.5%. Today it is over 17%. "

Schiraldi then implored courts and government officials to do whatever they can to reduce the population at Rikers, including compassionate release or modifying sentences.

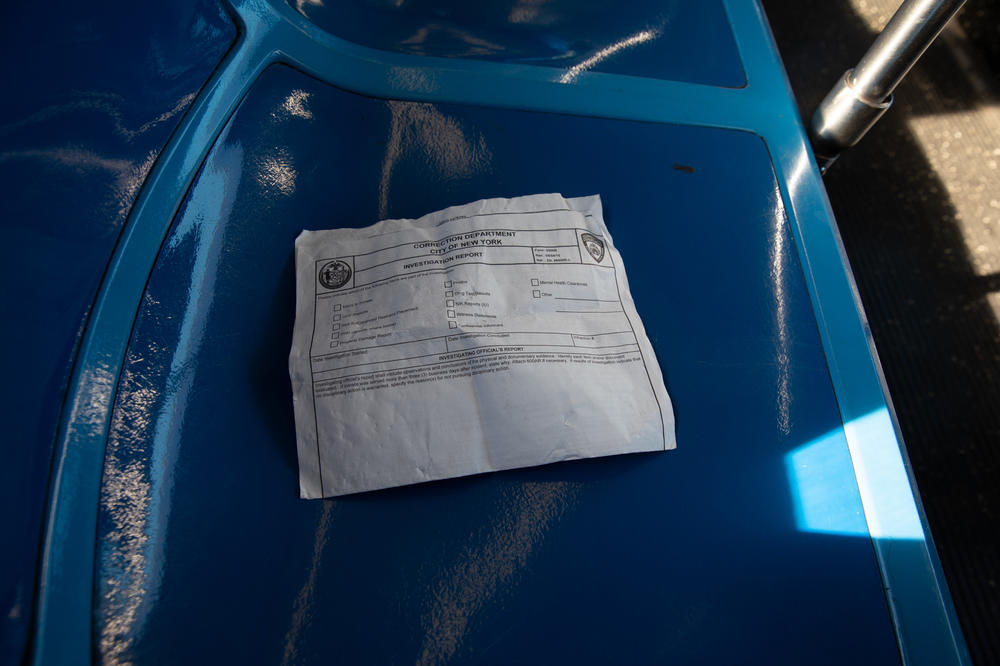

Tahanee Dunn, a Prisoners' Rights Attorney at the nonprofit, Bronx Defenders, says none of this surprises her. She's says she's filed around 20 complaints in the past six months, involving lack of access to food, medical attention, and violence.

"Incidents like this have been on the rise I would say in the past six to nine months," she says, "given what's been going on in the jails regarding COVID, certainly given the staffing issues, and the population has almost doubled since last April, when it was at its lowest."

Longstanding chaos at Rikers has led to its impending closure

There are plans to close Rikers by 2027 and replace it with smaller more modern jails across the city. New York City Department of Correction says, in the meantime, there's been progress at ameliorating conditions on the island.

In a statement to NPR, a spokesperson said, "We have worked aggressively to improve unacceptable conditions and thanks to those efforts, more officers are reporting to work, overcrowding and long waits in intake have ceased, and more resources are readily available. The physical and emotional wellbeing of people in our custody is our highest priority. We'll continue building on our progress to make Rikers safer for everyone who lives and works there."

The spokesperson also points to a recent report indicating that use of force by correctional staff declined by 11%.

In response to the outcry over conditions at the jail, last September officials released nearly 200 detainees who were in for technical parole violations. A few weeks later, more than 200 women and trans inmates were moved to facilities upstate. Still, activists say these moves have barely made a dent in the crisis at Rikers.

On the bus to Rikers along the East River, this mom thinks "about the lives that go over the water, and never come out"

The Q100 finally arrives, and the women file on. As it rumbles over the bridge, over the East River, and onto Rikers Island, the passengers get real quiet. Came'e Lee breaks the silence.

"My mind thinks about so much when I'm on that bus," she says. "Especially when it's time to go over that water. I think about the lives that go over the water, and never come out."

Inside Rikers, Came'e Lee spends about two and a half hours shuffling between waiting rooms, doing security checks.

The visitation room is bare. Dark cubicles are separated by plexiglass.

Finally Lee's son appears. He's disheveled, and his voice is hoarse. He says he's not getting food regularly.

She presses her hands and face against the plexiglass pane that separates them. He does too. For a moment they look like statues. Until she whispers something across the divide.

The island does something strange to time, it stretches it, it freezes it. Lee and the other women have been in here for six hours, though it feels shorter. They nearly miss their bus that's about to leave.

Lee settles into her seat, catching her breath. I ask Lee what she whispered to her son.

"I love you. I love you consistently. I love you consistently."

The sun is setting.

She looks out the window, and closes her eyes, as the Q100 bus makes its way back over the bridge.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content