Caption

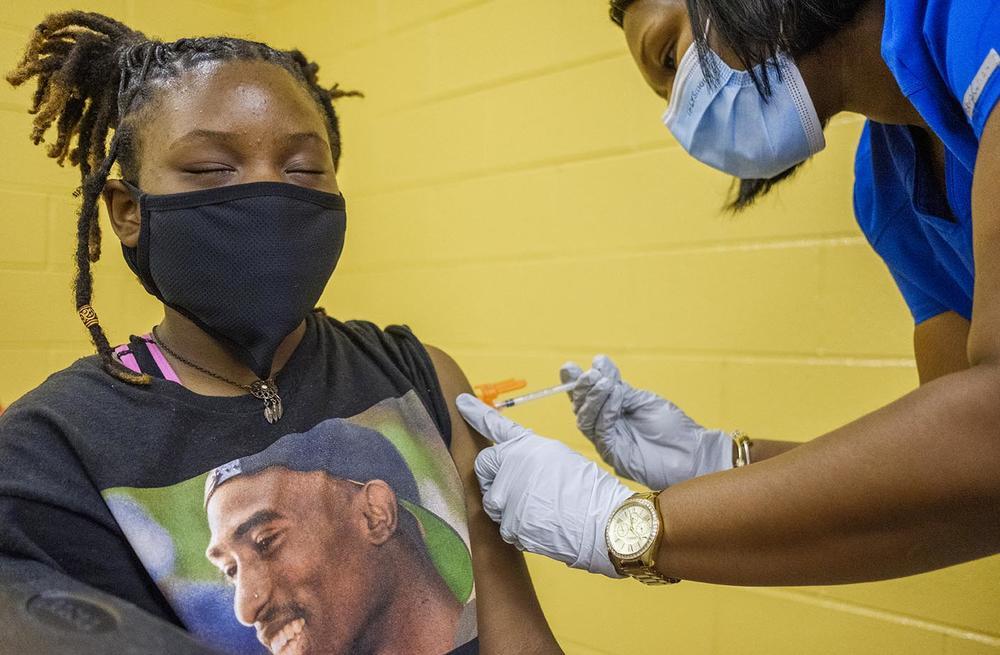

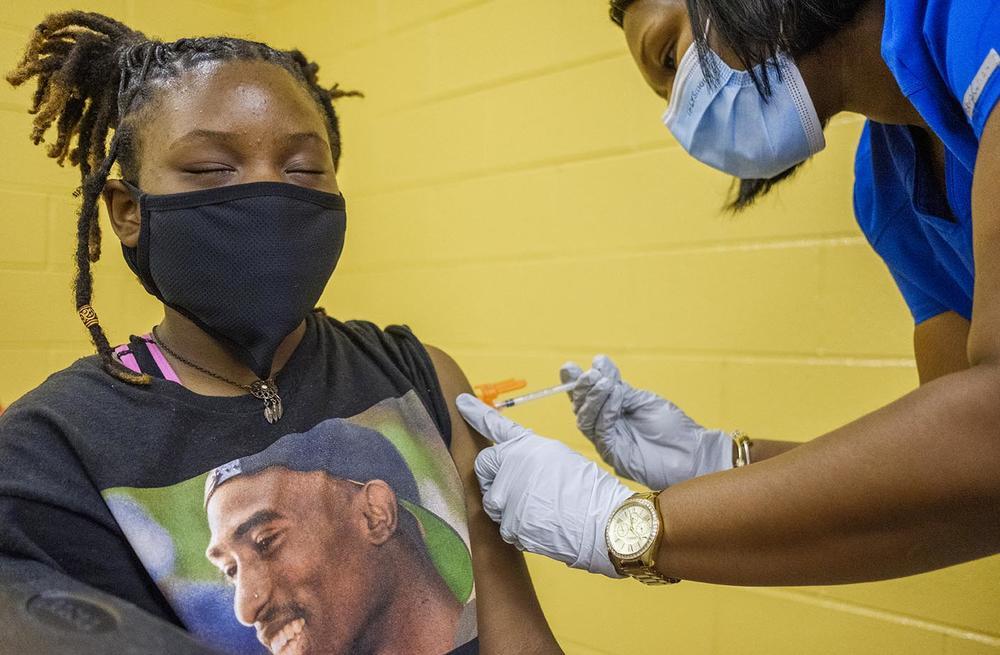

Bibb County middle school student Sade Veal gets her first dose of the Pfizer COVID vaccine at a back to school event sponsored by Bibb County Schools in 2021.

Credit: Grant Blankenship/GPB

Bibb County middle school student Sade Veal gets her first dose of the Pfizer COVID vaccine at a back to school event sponsored by Bibb County Schools in 2021.

The head of public health for the state of Georgia, Dr. Kathleen Toomey, said she is very worried that bills in the Georgia Senate could undo decades of progress in infectious disease eradication among children.

“In the many years I've worked in public health, this is probably the first time I actually am worrying that we may lose our childhood immunization levels,” Toomey said during remarks closing the February meeting of the state Board of Public Health on Tuesday.

“There has been so much visibility about mandates and vaccines and negativity and polarization around COVID that, unfortunately, it's spilled over into childhood immunizations, with some very real threats,” Toomey continued.

Currently two bills, Senate bills 372 and 345, are in committee. Both bills have been promoted as being explicitly about stopping mandated proof of COVID vaccination to access government services.

But neither of the bills includes the words "COVID" or "coronavirus." Instead, they would extend the ban on vaccination proof, or any mandate to be vaccinated, to any vaccine at all.

SB 372, the newer of the two bills, would exempt schools from the ban.

Dr. Toomey said by looking to score political points, politicians run the risk of reintroducing the public to diseases they don’t even remember by ending what is now a mandatory schedule of childhood vaccinations.

“Who's old enough to remember polio and who lined up at schools back in the ‘60s?” she asked. “But also I took care of kids with Haemophilus influenza B.”

The vaccine for Haemophilus influenza B, or HiB, is administered to children starting at two months of age in Georgia.

“I had children seize in my arms, had children crippled from Haemophilus disease in their joints,” Dr. Toomey said. “And now most parents have no idea what Haemophilus influenza B is because we have eliminated it here.”

Dr. Toomey concluded by calling the trends a dangerous gap in communication between medical experts, politicians and the public — a gap that has to be closed, for the health of all.