Section Branding

Header Content

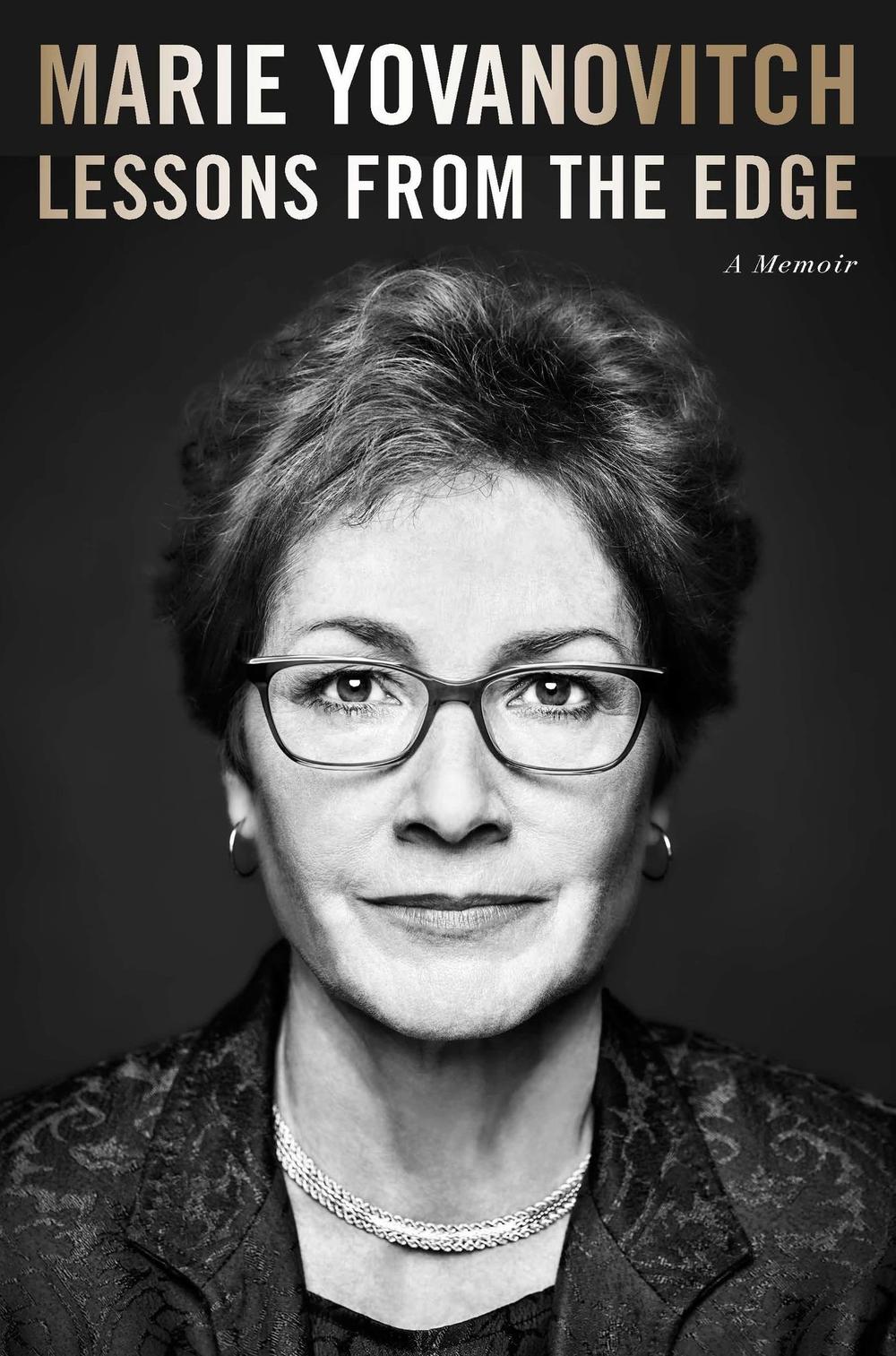

Marie Yovanovitch reflects on disinformation and her removal as ambassador to Ukraine

Primary Content

For any career foreign service officer to rise to the level of ambassador, it takes merit, timing and more than a little luck. Marie Yovanovitch, known to many as Masha, had all three — up until a point.

Her memoir, Lessons From the Edge, is a front row seat to the disinformation campaign that ultimately saw her removed from her last overseas post: U.S. ambassador to Ukraine.

This book also provides insight into the post-Soviet Union politics of Russia and Ukraine, both now dominating the news. And it pays homage to Foreign Service Officers (FSOs) and the work they do, and a career that still remains a mystery to many Americans.

To understand the former, she starts with the latter.

Yovanovitch entered the Foreign Service in 1986, where diplomats were overwhelmingly the "pale, male, Yale" model. She writes that she had one boss tell her parents "women don't belong in the foreign service. They can't do the job." (He would also tell her that of the people that he supervised, only women and minorities made it into the senior ranks of the Foreign Service, something statistics even today show is not the case.)

It was far from guaranteed that Yovanovitch would stay with State. At the start, she didn't have much luck. She didn't get the cone, State's term for job specialty, that she wanted. Instead of a political job, she was assigned to a management specialty. She had some bad bosses, and in her first tour she literally had corruption (the nephew of the leader of the country) come knocking at her door.

Still, she wanted to work in foreign affairs and to help represent and fight for American interests and values. And, like many others who enter public service, she says she wanted to "find a way to give back to the country that had given the Yovanovitch family a home." (Her mother and father had both survived the Nazi occupation of Europe.)

Luck finally intervened with a string of good bosses and some good job opportunities doing the political work she wanted. It was not glamorous. It often entailed long hours, sometimes in dangerous situations.

Yovanovitch also benefitted from one woman in particular: Alison Palmer. She sued the State Department for discrimination and won. In a case of good timing, part of the settlement included allowing 14 female FSOs who had been placed in the management or consular cones to move to political. Yovanovitch competed for one of the slots and got it. Still, it's not something she talked about until now. "I wanted to succeed or fail on the merits, not because I was a woman benefitting from the lawsuit," she writes. "I hadn't fully realized that 'merit' is a meaningless term if it's not judged on a level playing field." Given some of the comments that came her way about women in the foreign service, it's not surprising. But she's talking about it now, because sometimes persistence and hard work aren't enough. "Sometimes we also need an iconoclast," she writes.

For someone who climbed to the highest ranks in the foreign service, she is also honest about the self-doubt that tagged along. Her go-to seemed to be to keep her head down and do the work. In some ways, one would have hoped that an earlier lesson she learned — that if she didn't speak up for herself, no one else would — would have been her go-to move instead.

Career ambassadors don't usually become household names. Yovanovitch did for all the wrong reasons, none of them having to do with how she did her job. Rather, it was because she was doing her job — which included encouraging Ukraine's fledgling democracy and supporting true anti-corruption efforts — that led her to cross some wrong (and corrupt) Ukrainians. For an FSO who had spent years working in this region of the world, she writes, "I'd seen plenty of whisper campaigns and smear efforts in my many years of working in the former Soviet Union, Americans had never been among the key players driving them." Until now.

Domestic politics made its way to Ukraine. She was warned by several people that Rudy Giuliani, former President Donald Trump's personal lawyer, was trying "to spin a story that Vice President Joe Biden had acted corruptly" when he was the point person for Ukraine during the Obama administration. Giuliani turned his ire on Yovanovitch, saying she was corrupt, she was working against Trump, and spreading other lies about her. "I was worried that if I opened up about what was happening, even to friends, I would be dismissed as a crazy lady with an enormous ego: Rudy Giuliani, hero of 9/11, was trying to dig up dirt in Ukraine about former Vice President Biden and smear me because I was getting in the way of his schemes. Would you have believed me? I barely believed myself at that point."

Political appointees, which ambassadors ultimately are whether they are political donors, political supporters or career FSOs, serve at the pleasure of the president. Yovanovitch knows this and writes more than a few times throughout the book that Trump could have had her removed at any time. It was not necessary, she writes, to drag her through the mud to remove her. Her disappointment in the State Department, and then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who didn't stick up for her, is palpable. (And it was, apparently, a touchy subject for Pompeo.)

It was John Sullivan, then deputy secretary of state and now U.S. ambassador to Russia, who ultimately told her she was being recalled from Ukraine. It was not for cause, but because the disinformation campaign had ultimately been successful. Still, Sullivan put it in terms that she understood: the President had lost confidence in her. It was, she writes, a "soul-crushing moment." She learned at that meeting that for over a year Trump had been calling Pompeo demanding that she be pulled out of Ukraine. The Department, Sullivan said, was doing it now for "her protection."

She takes issue with that. Looking back on it, she thinks it had more to do with protecting Pompeo and Trump. It's one thing to fire your secretary of state by tweet, it's something else to do that to a career ambassador. It would be so unusual that "it would have prompted a lot of questions from Congress and the press." She goes on to write, "This wasn't about protecting me, it was about Pompeo protecting himself and the president from charges of diplomatic malpractice." And she thinks that was also the case when Pompeo tried to stop State Department officials from giving depositions to Congress as it started impeachment investigations.

Yovanovitch was subpoenaed and did testify, privately and later publicly, because she respected Congress's oversight role — regardless of which party was in power (something former Rep. Pompeo might have more understanding for than Sec. Pompeo), and because she was a nonpartisan public servant. "Each of us knew that our oath to the Constitution comes first," she writes. And while she was viewed as a hero by some in America for speaking out, she also thinks "it's a sad testament to the serious challenge of our times that a public servant speaking the truth could be seen as heroic."

A woman who served Republican and Democratic administrations, she spends much of this book stressing the non-partisan nature of the job. In these hyper-partisan times it may be hard to believe, but that is the mandate for FSOs and other public servants. The job is implementing the foreign policy of the president — whether he or she be a Democrat or a Republican. That's not to say Yovanovitch didn't have her own private concerns about Trump in 2016, but as she told her staff at the time they were "Team America." She could have retired then, but stayed: "I believed that I had the experience and the expertise to make a difference in Ukraine, and I owed it to the new administration to share my insights. Plus I loved what I was doing, and I didn't want to leave."

She didn't seek to be an iconoclast. She writes that in testifying she didn't want to burn down the house. If anything, she seems to have written this memoir not just to finally be able to speak up for herself, but also to inform people about the work FSOs do for America, supporting whoever is elected to lead.

Was it naïve? Maybe. Idealistic? Yes. But, perhaps, these are necessary qualities that help move people to become iconoclasts.

Caitlyn Kim is the Washington, D.C., reporter for Colorado Public Radio. She worked as a U.S. diplomat from 2013-2018, serving in Estonia, Pakistan and D.C.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content