Caption

Rosario A westside Atlanta neighborhood contaminated with lead has been added to the EPA’s Superfund priority list, freeing up more federal funding for long-term cleanup.

Credit: Georgia Health News

Rosario A westside Atlanta neighborhood contaminated with lead has been added to the EPA’s Superfund priority list, freeing up more federal funding for long-term cleanup.

A westside Atlanta neighborhood contaminated with lead has been added to the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund priority list, freeing up more federal funding for long-term cleanup.

The English Avenue area is one of 12 sites across the nation that the EPA added to its Superfund National Priorities List (NPL), the agency announced Thursday.

More than 2,000 properties in the EPA target zone are being investigated for lead in the soil.

Out of 951 properties already sampled there, about 40%, or 377, had levels of lead above 400 parts per million, the EPA threshold that calls for cleanup. The EPA has said 116 have been remediated, meaning the situation has been corrected.

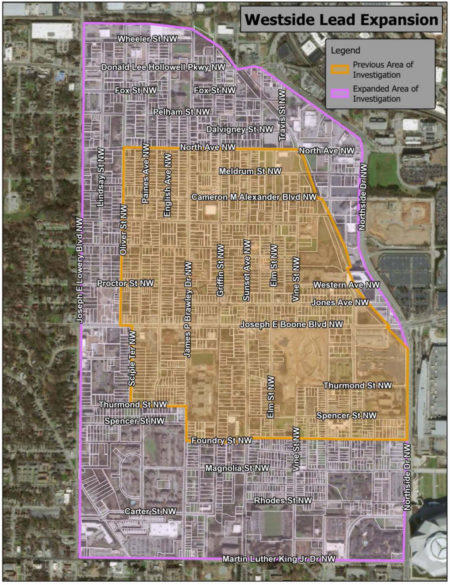

Expanded Westside lead study area.

The EPA and local officials held a news conference Friday at a neighborhood church, and made a pitch for more tenants and landowners in the area to agree to testing of their soil for lead.

The overall cost of the cleanup is now estimated at $50 million, and the work is projected to be finished in 2028.

Rosario Hernandez, who was among the first residents of the area whose soil was analyzed, emphasized the dangers of lead poisoning at the press conference, held at New Life Covenant Church.

“We’ve got to get those kids tested,’’ said Hernandez, who has become a leader in educating community residents about the contamination.

Using Georgia Department of Public Health data, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution previously found historical evidence of lead poisoning in children in ZIP codes in the area.

The federal Superfund program has the responsibility of identifying dangerously polluted sites around the nation, cleaning them up and, when possible, holding polluters financially accountable. There are thousands of Superfund sites, but a relatively small percentage are on the NPL, meaning they are especially dangerous.

Lead, a naturally occurring element that has been mined and used by humans for thousands of years, is a powerful neurotoxin that’s especially dangerous for children. In recent decades, as lead’s full dangers have become clear, governments and industries have sought to drastically reduce its presence in the environment.

The NPL designation of the English Avenue area “means that it is one of the most contaminated sites in the U.S.,’’ said Eri Saikawa, an Emory University scientist who led a student team that uncovered the lead problem in 2018.

The Emory findings kicked off an EPA investigation that ultimately unearthed large amounts of slag in the area.

Slag, which can contain lead, is a byproduct of smelting. The west Atlanta area contained foundries, and many years ago, people used slag to fill in low-lying areas in the neighborhood.

Saikawa told GHN that she believes some properties outside the investigation zone also have substantial amounts of lead in their soil.

Pieces of slag in Westside neighborhood.

An EPA official said the agency isn’t ruling out a further expansion of the investigation zone. “The data will drive the decision to expand,’’ said Leigh Lattimore.

The NPL sites represent significant human health and environmental risks, the EPA says.

“No community deserves to have contaminated sites near where they live, work, play, and go to school. Nearly 2 out of 3 of the sites being proposed or added to the priorities list are in overburdened or underserved communities,” said EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan in a statement this week.

The investigation zone, a low-income, mostly minority community near Mercedes-Benz Stadium, is bordered by Wheeler Street, Joseph E. Lowery Boulevard, south Martin Luther King Jr. Drive and Northside Drive.

An infrastructure bill recently passed by Congress provided $3.5 billion for such cleanups.

Carlton Waterhouse, deputy assistant administrator for the EPA’s Office of Land and Emergency Management, said at the press conference that about 73 million Americans live within three miles of a Superfund site. Many are people of color and low income, he said.

“Environmental justice is a top priority,’’ he added.

Jim Woolford, a former director of the EPA Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation, said in a statement that “updates to the NPL frequently go unnoticed, but this is a critical step in the Superfund cleanup process as it sets the stage for further EPA actions to protect the health and well-being of communities, states, and tribes adversely affected by releases from these sites.”

Woolford is a member of the Environmental Protection Network, a group of more than 550 former EPA career staff and confirmation-level appointees from Democratic and Republican administrations.

There are problems elsewhere in Atlanta, Saikawa said. Her research team, in conjunction with government agencies, has found slag in some yards in these areas.

And in south Atlanta, they also found high levels of lead in the soil near the TAV Holdings metal processing plant, a situation that the EPA is investigating.

Even at low levels, lead can damage children’s brains, lowering intelligence and weakening their powers of self-control and concentration, researchers have found. At higher levels, lead can affect growth, and it can replace iron in the blood, leading to anemia and fatigue.

There is no safe level of lead exposure, the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says.

The hazards of lead were highlighted in 2014, after drinking water for the city of Flint, Mich., was contaminated with lead, exposing thousands of children to the hazard.

A bill in the Georgia Legislature, sponsored by Rep. Katie Dempsey (R-Rome), would lower the level of lead in children’s blood that would trigger state regulatory action, which includes testing, warning letters and required remediation. That poisoning level would be put at the CDC guideline of 3.5 micrograms per deciliter, much lower than Georgia’s current threshold, which experts say leaves many children at risk.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Georgia Health News.