Section Branding

Header Content

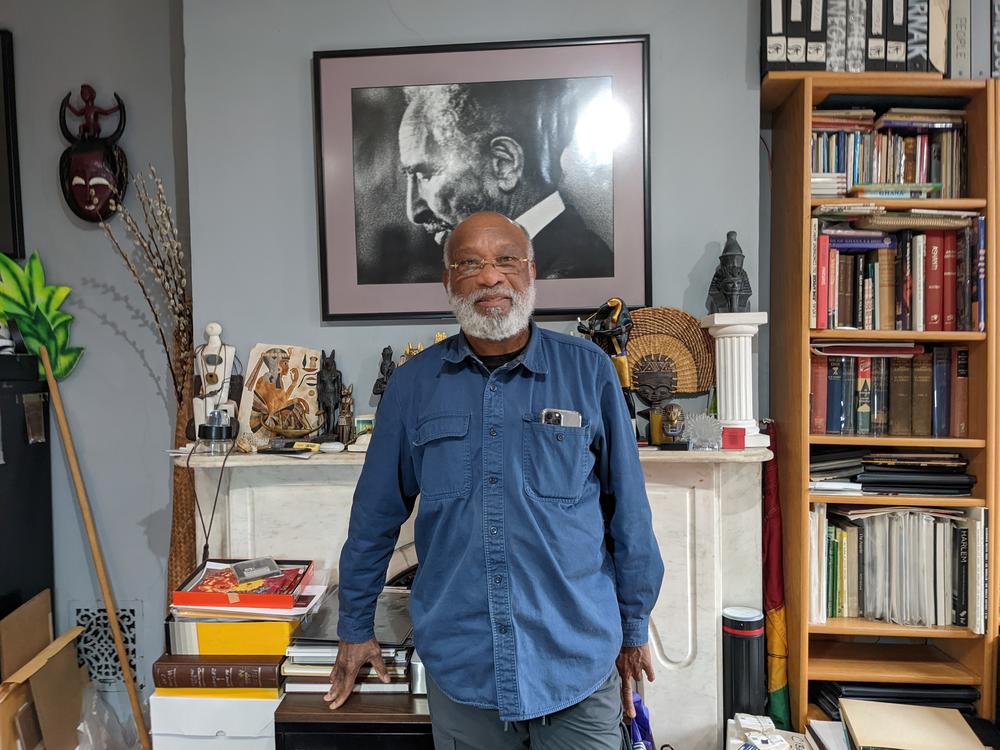

Chester Higgins' camera brings a 360 degree view to Black life

Primary Content

Not long after I arrived at his Brooklyn brownstone, Chester Higgins started telling me about "The Spirit." He was nine years old when "The Spirit" visited him in his bedroom in rural New Brockton, Alabama.

"There's this Black man who's standing in a very calm, still position," Higgins said. "His eyes are closed and gradually his eyes open, he raises up his hands. As he's walking towards me and extending his hand and says, 'I come for you.'"

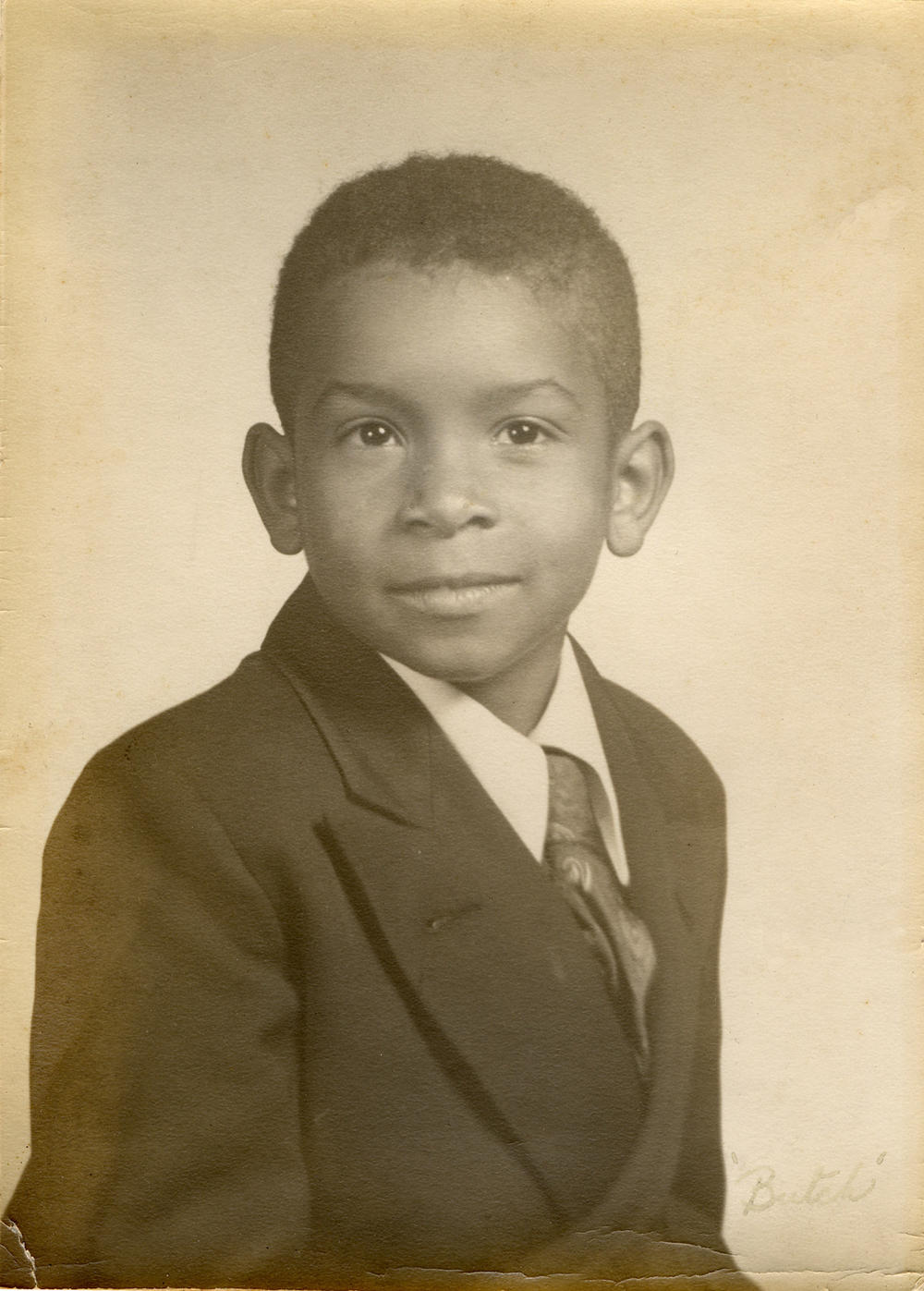

Higgins was terrified but his grandfather, a Baptist minister, explained the incident as an apparition and interpreted it as the boy's calling to the ministry. In September 1957— two months before his 10th birthday— Higgins was presented with a minister's license and started preaching at local churches.

But when Higgins went off to Tuskegee Institute, he left his religious calling behind. As business manager of the student newspaper, he encouraged advertisers to buy bigger ads with photos in them. This is how Higgins stumbled into photography.

From minister to photographer

At the home of the college's professional photographer, Higgins was moved by portraits of poor farmers on their way to market. Higgins got the photographer to teach him how to use his camera, borrowed it and shot photos of his family back in New Brockton. Seeing his relatives' faces in framed portraits on the walls of their homes was like being paid, he said.

"They found a sense of agency in themselves that they hadn't seen before, that reaffirmed their sense of worthiness," Higgins said. "I picked up the camera out of love for my family. I did not have a long term plan with the camera. But what changed that is the civil rights movement."

In the late 1960's Higgins was active in civil rights protests. He joined people picketing outside the mansion of Alabama's segregationist governor, George Wallace, in Montgomery. He didn't like the mainstream media's coverage of the civil rights protests.

"We weren't seen as American citizens petitioning our government," he recalled. "We were seen as potential arsonists, rapists or just thugs. It taught me that a picture never lies about the photographer."

Years later during a job interview with A.M. Rosenthal, the managing editor of The New York Times, Higgins said there were three things that were always missing in images of African-Americans: "decency, dignity and virtuous character."

Higgins decided that the best way to remedy the white media's depiction of African-Americans was to become a photographer. After his junior year at Tuskegee, he traveled to New York in the summer of 1969 and cold-called a number of big-circulation picture magazines, stressing that he was seeking feedback from a photo editor, not a job. Higgins will tell you that "The Spirit" was responsible for him meeting Arthur Rothstein, the director of photography at Look magazine.

"The Spirit brought this man into my life," said Higgins. "The door opens and here he is."

Rothstein, one of the giants of American photography, was clearly impressed with Higgins who explained that his goal as a photographer was to "change the way the media portrays my people."

Higgins said Rothstein took him under his wing because he could sense Higgins' "desperate energy" to master the craft of photography.

Rothstein was so keen on the college kid from Alabama that he gave him 35mm film and critiqued Higgins' work. Higgins remembered one day when Rothstein took four sheets of paper from his desk and cropped one of Higgins' pictures.

"He calls me over and says, 'Here, take a look.' I went and I looked and I was amazed," Higgins recalled. "I asked him, 'Was that my picture?' He said, 'Yes, that's your picture but you didn't know it. All this other stuff was competing with it and you didn't know what to zero in on.'"

I wanted to have my images on the world stage

After graduation, Higgins moved to New York and spent several years freelancing before being hired as a staff photographer at The New York Times in 1975. During the 39 years Higgins worked at the newspaper, some 40% of his images, he says, were of people of color. And he points with pride to the fact that he got a picture of Kwanzaa published in the paper almost every year, as well as images of a Coney Island beach ceremony commemorating the enslaved Africans who perished in the Atlantic Ocean during the Middle Passage.

"This is what Rothstein trained me for," said Higgins. "I wanted to have my images on the world stage."

Among those who have appreciated Higgins' work over the years is Lonnie Bunch, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. When Bunch served as founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, he made sure that it acquired some of Higgins' images.

"Chester is someone who has captured the last 40 years of Black America in powerful ways" Bunch told NPR. "He elevated photography from documentary to fine art."

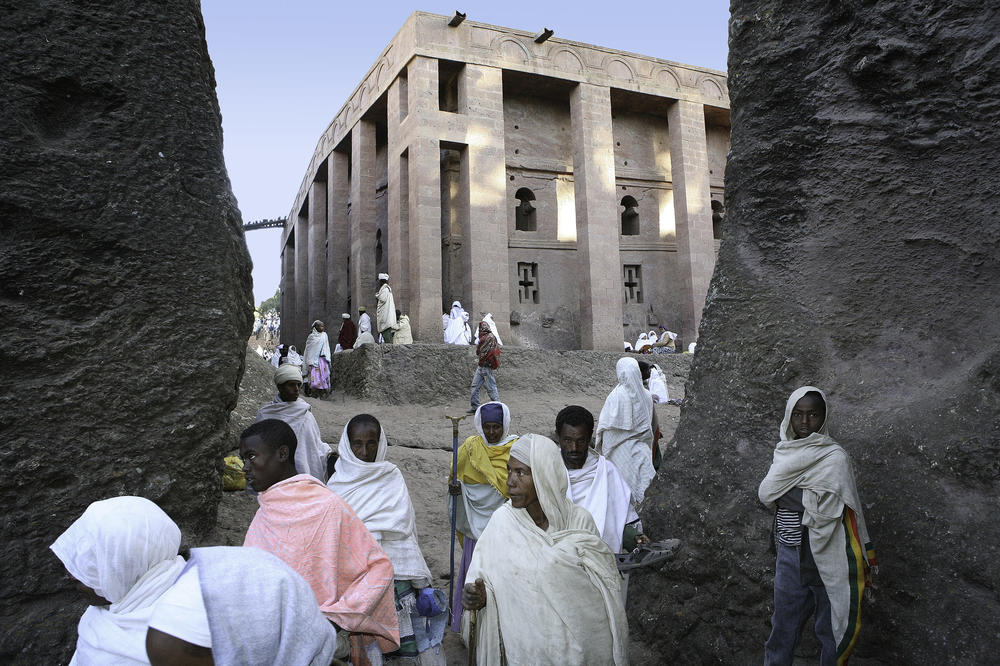

Bunch is aware that Higgins has made close to 50 trips to Africa and admires the photographer's effort to portray the continent's humanity in a way that might foster a deeper connection for other African-Americans.

"He's not capturing an Africa that's flawed, he's not capturing an Africa that is broken," said Bunch. "He's capturing an Africa that has a spirit of hope, of possibility that in some ways he believes will shape the African-American experience as well."

A life-long assignment in Africa

Higgins made his first trip to Africa in 1971, traveling to Senegal for an Essence magazine assignment. For most of the time he worked for The New York Times he spent his vacations in Africa, often commissioning custom made suits made of traditional African patterns. Now 75, Higgins hasn't stopped going to the continent to document its history and culture. He spent the first month of 2022 in Egypt.

"Being in Africa, I've discovered, is quite a relief for me because... [when I go, I'm] in the majority. I don't have to worry about people looking at my color and [I'm] a target, people not knowing me and they hate me. I've found that the whole stress of racism just lifts off your shoulder."

Higgins often refers to Africans as "my cousins."

He's been to Egypt 20 times, most recently to shoot photos of tombs. His latest book, The Sacred Nile, presents images of pyramids, rock-hewn churches, tombs and other religious monuments along the River Nile. Higgins says his trips to the continent have become his life-long assignment.

"My overall assignment was to create a visual encyclopedia of the life and times of people of African descent," Higgins said. "I just lumbered along, following The Spirit, following my interests. And that's what I still do.

On March 24, Higgins was presented with a lifetime achievement award by the Silurians Press Club in New York, the first time a photographer has been honored by the group. Former New York Times reporter Joseph Berger praised Higgins for raising the consciousness of the entire newsroom.

"Chester has always been a man on a spiritual mission, striving to find the humanity, the dignity and the grace in everyone," said Berger who worked with Higgins over the course of 30 years. "Just look at the photos of Joyce Dinkins adjusting her husband's tie before his inauguration as mayor or Amiri Baraka jitterbugging with Maya Angelou at Harlem's Schomburg Center. Higgins, he said, "viewed his job as a calling and the taking of photographs as a sacrament."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.