Section Branding

Header Content

Why there are growing fears the U.S. is headed to a recession

Primary Content

Warning lights are flashing for the U.S. economy.

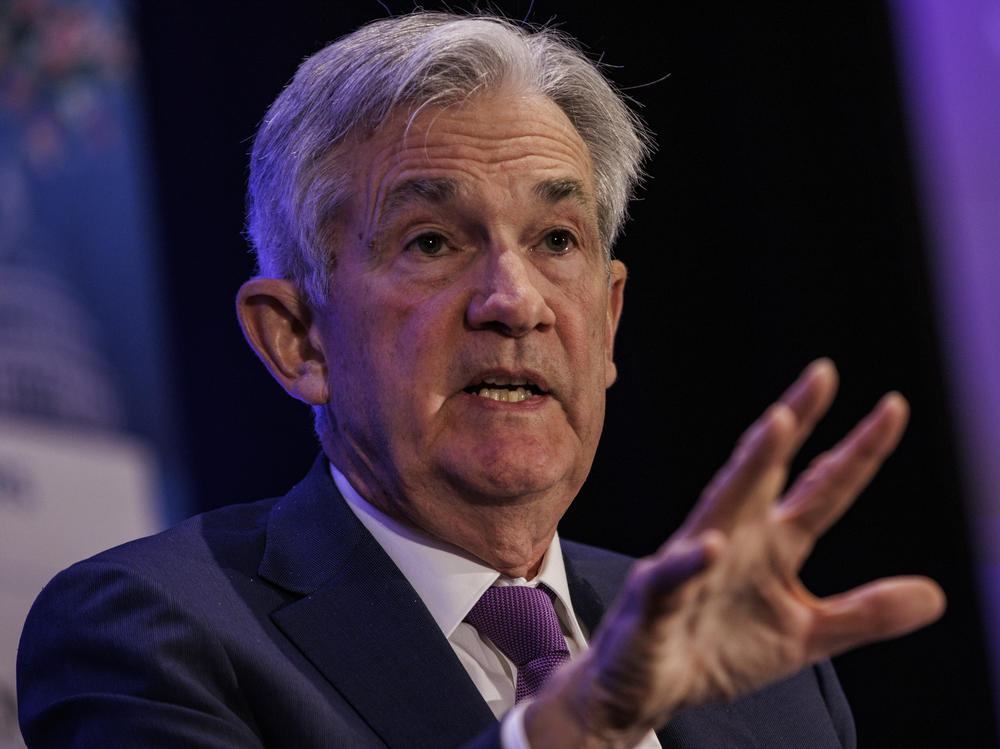

A growing number of forecasters now believe a recession is on the horizon as the Federal Reserve gears up to raise interest rates sharply to combat the highest inflation in more than 40 years.

It's an unusual outlook at a time when the economy is strong by many measures. Employers have added nearly 6.5 million jobs in the last 12 months and unemployment has fallen to just 3.6%.

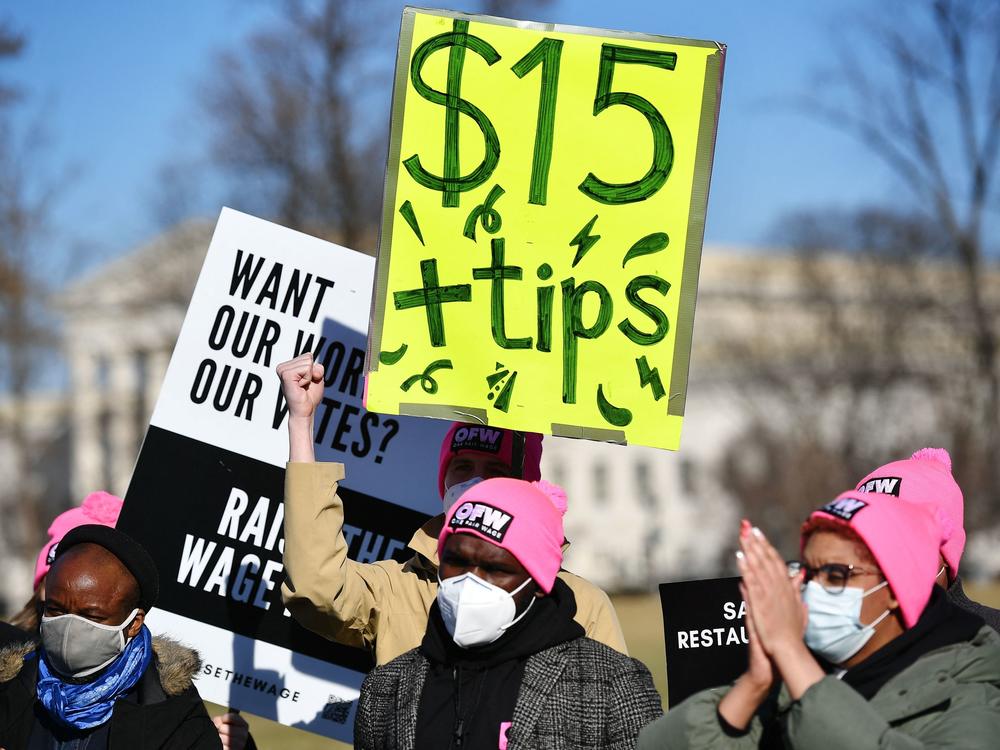

But it's that strong economy and, particularly, the sizzling labor market as employers try to hire more workers to meet surging consumer demand that has economists concerned.

As employers scramble to find scarce workers, they're bidding up wages, and that's helping to push inflation even further above the Fed's target of 2%.

As a result, economist Matthew Luzzetti believes the Federal Reserve will have no choice but to crack down hard, with significantly higher interest rates.

Luzzetti predicts that those aggressive rate hikes will push the economy into a mild recession by late next year.

"It's probably surprising to be talking about recessions at this point, given the momentum that we've seen, particularly in the labor market," says Luzzetti, chief U.S. economist for Deutsche Bank.

"The ultimate conclusion is that we are having very strong growth, but it is inflationary growth," he adds.

Other forecasters are also getting nervous. Economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal put the odds of recession in the next 12 months at 28%, up from 13% a year ago.

Inflation seems to be everywhere

For much of past year, the Fed thought inflation was primarily the result of supply chain snarls that would work themselves out once the pandemic eased.

Instead, price hikes have accelerated. Consumer prices in March were up 8.5% from a year ago according to data out on Tuesday — the sharpest increase since December 1981.

Relief on the supply side is taking longer than many analysts expected, and Russia's invasion of Ukraine has only added to disruption, jeopardizing exports of both food and energy.

"We continue to push out our expectations of when these supply chain issues will be resolved," Luzzetti says. "And that is one area where the recent invasion of Ukraine has exacerbated and elongated those price pressures and the supply chain issues that we are to face."

Tuesday's inflation report did show some relief from pandemic backlogs. The price of used cars — which soared last year when a shortage of semiconductors hampered new car production — fell 3.8% in March.

But prices for many other items continued to climb, thanks to consumers' insatiable demand for goods and services.

If inflation remains elevated, workers may demand even higher wages — a recipe for the kind of wage-price spiral that contributed to runaway inflation in the 1970s.

The Fed's tricky balance

Last month, the Fed began raising interest rates in an effort to tamp down consumer demand and bring prices under control. Ideally, the central bank would cool off inflation without sending a chill through the whole economy.

The monetary thermostat is not very precise, however. Some forecasters worry that the Fed's chance of getting it just right are not good.

"It could happen," says former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers. "But I don't think it's terribly likely."

Summers has been arguing for more than a year that both Congress and the Fed were pumping too much money into the economy, with big COVID-19 relief payments and rock-bottom interest rates.

Summers argues that it would have been better to turn the taps off sooner. Mopping up now from the resulting high inflation is likely to be painful.

"Now the bathtub is overflowing," Summers says. "And it's much easier to stop a bathtub from overflowing than it is to get the water back."

Why the Fed wants a so-called 'soft landing'

Not all forecasters share that gloomy outlook. In the Wall Street Journal's survey, 63% of economists said they thought the Fed could engineer a "soft landing," bringing inflation under control without triggering a recession.

Brian Deese, the director of President Biden's National Economic Council, acknowledges the economic challenge that high inflation poses but argues that the strong job market and extra money in consumers' bank accounts should help.

"The United States is better positioned than any county in the world to navigate through this very difficult period of time," Deese said last week, at a forum sponsored by The Christian Science Monitor.

Summers says he understands why both the White House and the Fed were eager to let the economy run hot and boost workers' wages.

"Increases in demand can be profoundly good for workers," he says. "But if they're unsustainable and they necessitate subsequent recessions, then they ultimately boomerang."

Summers, a Democrat who served in the Clinton and Obama administrations, also has a warning for the Biden administration and congressional Democrats.

Voters' frustration with high inflation helped to fuel Republican victories in the past, he says, such as Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

The U.S. will now get a chance to see whether that history repeats in midterm elections later this year.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.