Section Branding

Header Content

Art bearing witness to the agonies of war

Primary Content

Russia's monstrous invasion of Ukraine has changed my newspaper reading habits. (Yes, I still get actual daily papers, just as I own actual radios. Eight, in fact. But I digress.) These days, I'm reading pictures more than text: horrific color photographs of decimated buildings, bloody bodies, and grieving citizens. There are babuskha women who must look like my great-great grandmother — she came from that part of the world (Lithuania).

An exhibition at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts shows four centuries of war images from their permanent collection. As They Saw It: Artists Witnessing War goes from 1520 to 1920, and gives powerful witness to the brutality of war, and how artforms have reflected it.

Pictures from the Crimean War — Russia's mid-1850s conflict on the peninsula with Britain, France and others — have particular resonance for today. Decades before iPhones and TV cameras, Roger Fenton documented the struggle, as early battlefield photographers began going to war.

Before them, it was up to artists to show what war was like. Winslow Homer is probably best known for his magnificent 19th century land and seascapes. But during the Civil War, Harper's Weekly magazine sent him — then a staff illustrator — to be a war artist, embedded at the front with the Union army. Homer was one of 30 artist-reporters to cover that conflict.

Clark Institute curator Anne Leonard says, "Homer made sketches whenever he could, then sent them back to the Harper's office in New York, where wood engravers transformed the sketches into print." A reported 200,000 subscribers could see them in the journal.

As a battle rages in the background, wounded Union soldiers are hauled over to medics who'll use knives to treat them. Amputations were common. You'd look in vain for signs of sanitation here. A medical assistant — pretty dapper in a tidy cape, clean trousers — carries a box on his back, filled with various implements the elderly bearded chief surgeon might need.

There was a boom in photography and portraits after the Civil War. Veterans had their pictures taken for souvenirs. This tintype, posed in a studio, is one of the few images of Black soldiers in the Civil War. The photographer is unknown. So is the soldier. But he wears his medal and his pride along with that polka dot bow tie, especially chosen for this portrait — of that we can be sure.

Cameras brought eye-witnessing lenses to war, and documentation took over from artistic "impressions" of reality. But one artist in particular — Francisco Goya of Spain — may have made the most lasting impressions when he took the horrors of war as his subject in the early 1800s, when Napoleon invaded his country and Portugal.

Goya's Disasters of War, a portfolio of 80 prints, was a personal, often anguished reaction to human suffering. "Goya is the standard by which war imagery is judged" says curator Anne Leonard. "He takes a clear-eyed, unsparing look."

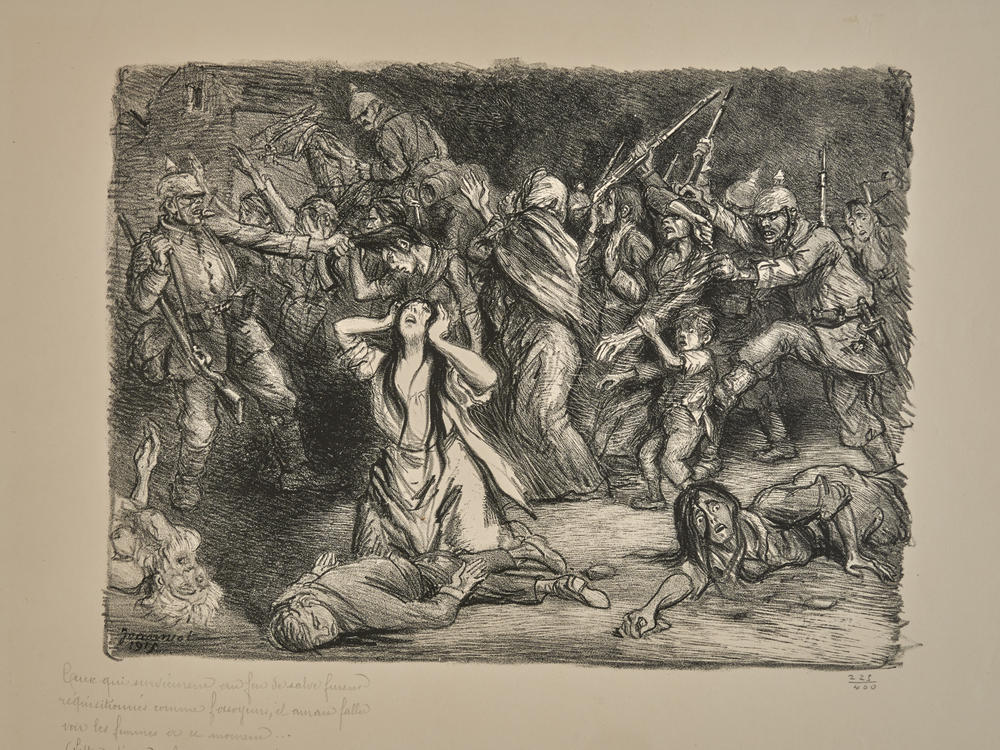

Goya's war art has inspired artists for centuries. In World War I, Swiss-Frenchman Pierre-Georges Jeanniot made lithographs of what he saw: civilian suffering and terror, much like photographs from 2022 Ukraine.

Can you, reader, see a common thread in this handful of images from the Clark Institute exhibition? Different media, different artists, different conflicts? Curator Anne Leonard sees "subjectivity." Each artist has his own take on war: "There's no one truth."

Beyond horror and brutality, she sees the power of art. "When images like these survive it's because they still speak to us," she says. They've survived their times. "If they do, it means there's something larger that they're saying."

Maybe the simplest observation came from a Union general in the American civil war. William Tecumseh Sherman said, so succinctly and memorably, "War is hell."

Art Where You're At is an informal series showcasing online offerings at museums you may not be able to visit.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.