Caption

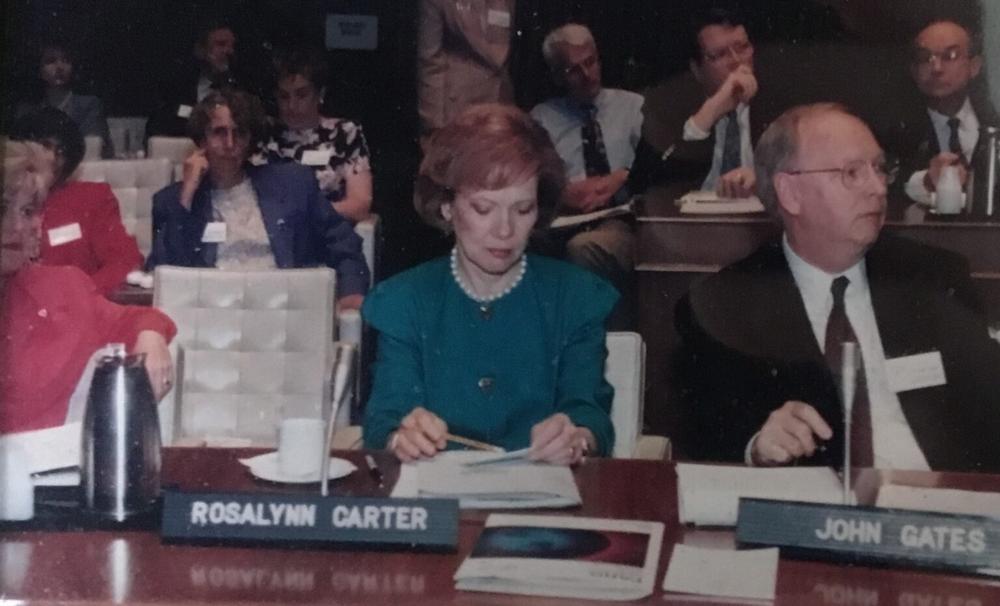

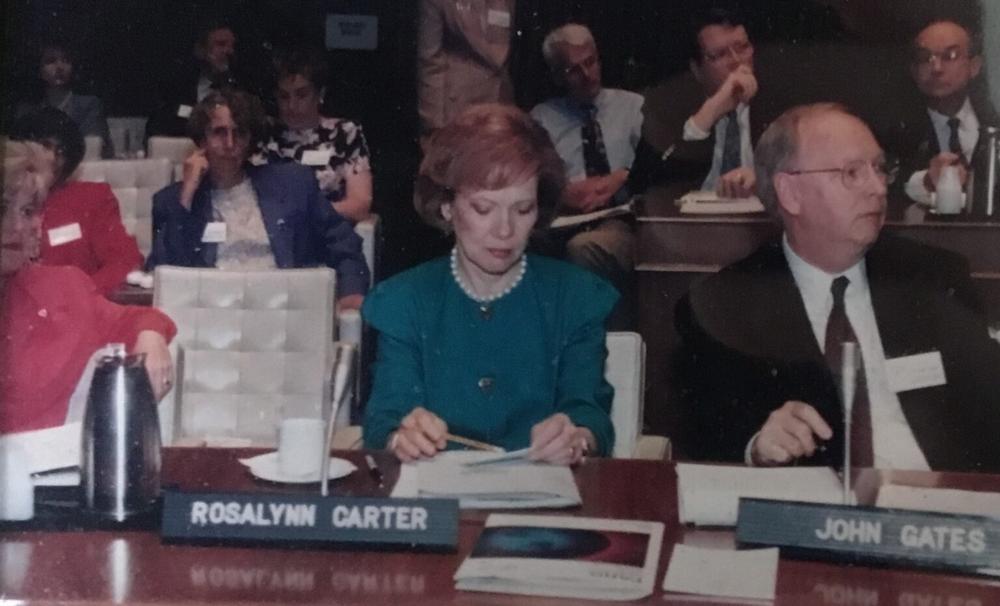

Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter and her long-time advisor Dr. John Gates sit together in 1993 during a forum on mental health in Washington D.C.

Credit: Photo provided by Marsha Gates

Former First Lady Rosalynn Carter and her long-time advisor Dr. John Gates sit together in 1993 during a forum on mental health in Washington D.C.

A former director of state mental health and disability services who was a longtime adviser to former first lady Rosalynn Carter is being remembered for his work lifting consumer voices.

Dr. John Gates, a former head of what is now known as the state Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, died in January from complications of a chronic heart condition. He was 81.

A celebration of life is planned Monday at the Carter Center, where he formerly led the center’s mental health program and continued to serve on the former first lady’s Mental Health Task Force and the advisory board of the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers until his death.

“Words cannot express my gratitude for all John did to help me with my work, as well as to improve the lives of countless people with mental health conditions,” Rosalynn Carter, a longtime leading advocate for mental health, wrote in a letter to Gates’ wife.

Gates started his decades-long career in Georgia working as a clinical psychologist at the once massive Central State Hospital in Milledgeville, which is a nearly 180-year-old facility with a dark and controversial history. He went on to serve as superintendent of Central State, which became accredited under his watch.

That experience instilled in Gates a lasting respect for state hospital workers, particularly as federal scrutiny and a shift toward community-based services has at times soured public perception of the state hospitals.

“What the state had to acknowledge was we were over utilizing our institutions,” said current DBHDD Commissioner Judy Fitzgerald, who saw Gates as a mentor. “So sometimes along with that came a little bit of disrespect for the fact that there was good and important work happening within the hospital walls.”

But those who knew Gates said he may best be remembered for his groundbreaking efforts to elevate patient perspectives in policy discussions.

“He would say, particularly about the advocacy organizations, ‘By the way, they’re wrong a lot, but you’ve still got to listen to them,” Fitzgerald said. “He just had such an appreciation for bringing diverse voices to the table, and back then, bringing people with the voice of lived experience in particular was not a popular or well understood thing to do. So, he really was a leader in that.”

Joel Slack experienced that firsthand. Slack became a mental health consumer advocate who was eager to push for changes from the inside after having negative experiences while being treated for severe depression in state and private hospitals in Maryland and Michigan.

Slack, who created a consumer advocacy training organization called the RESPECT Institute, said Gates granted him access to Georgia’s state hospitals in the late 1980s at a time when administrators were more likely to be wary of advocates like him.

In Gates he said he found a commissioner who was open to new perspectives that might expand his scope of understanding.

With Gates’ approval, Slack conducted surveys of Georgia’s state hospitals. He started in Thomasville, where he said his review brought about immediate improvements like the removal of barbed wire fence around the facility that Slack noted did not signal to patients they were arriving at a place of healing.

Gates continued to include consumer advocates in Carter Center programming, which Slack said encouraged leaders of mental health systems to go back home and include consumer advocates in their meetings.

“He raised the bar for other administrators around the country to have more consumer participation,” Slack said. “Consumer advocates can pound and pound and pound from the outside. They can pound their fists on the table. (It takes) an administrator like John opens up the door and lets you in and says ‘OK let’s talk. Let me hear you.’”

Gates’ influence can be seen today at the state Board of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities meetings. A “recovery speaker” routinely kicks off the board’s meetings as a way of highlighting the success of those who have overcome mental illness or substance abuse disorder.

Gates did not live to see Gov. Brian Kemp sign into law a sweeping mental health measure this session. But Fitzgerald said she spoke with him before the session when there was already a groundswell of bipartisan support for requiring insurers to treat mental health and substance abuse disorder the same as physical care, as required by federal law. The Carter Center has long pushed nationally for behavioral health parity.

“He would have been grinning ear to ear at all the people who were squeezing onto the Capitol steps in a bipartisan way to say we support mental health,” she added. “I think he would say he would have never believed that would have been possible and that mental health has really made it to the big table now.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Georgia Recorder.