Caption

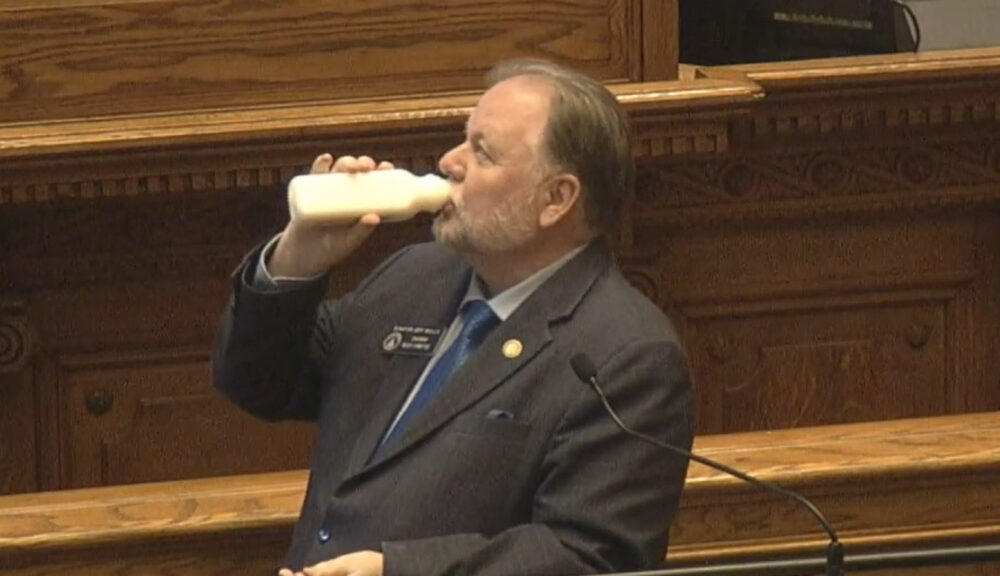

Republican Sen. Jeff Mullis of Chickamauga drinks raw milk, marked for pet consumption, while presenting a bill to legalize it for human consumption during the Senate floor session in this screenshot on April 1, 2022.

Credit: Georgia General Assembly