Caption

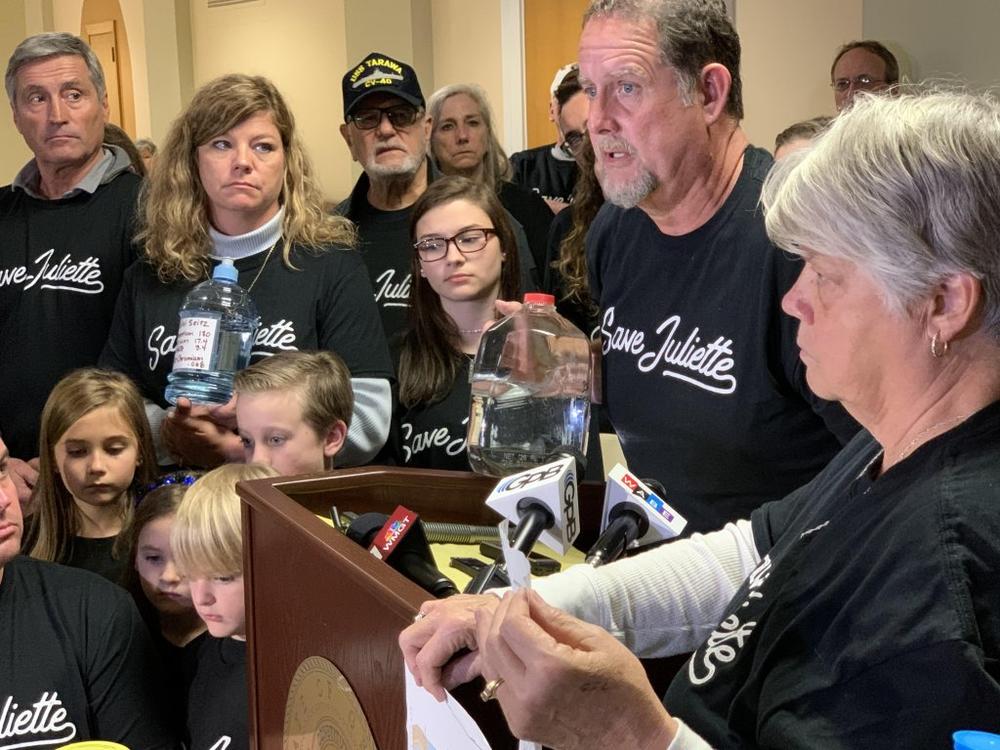

Gloria Hammond, far right, was part of the large group of Juliette residents who visited the state Capitol two years ago to push state elected officials to intervene in Georgia Power’s coal ash disposal plans. The county is now installing a water line so residents can access clean water, but Hammond says residents still want the coal ash moved to a lined landfill.

Credit: Georgia Recorder file photo