Section Branding

Header Content

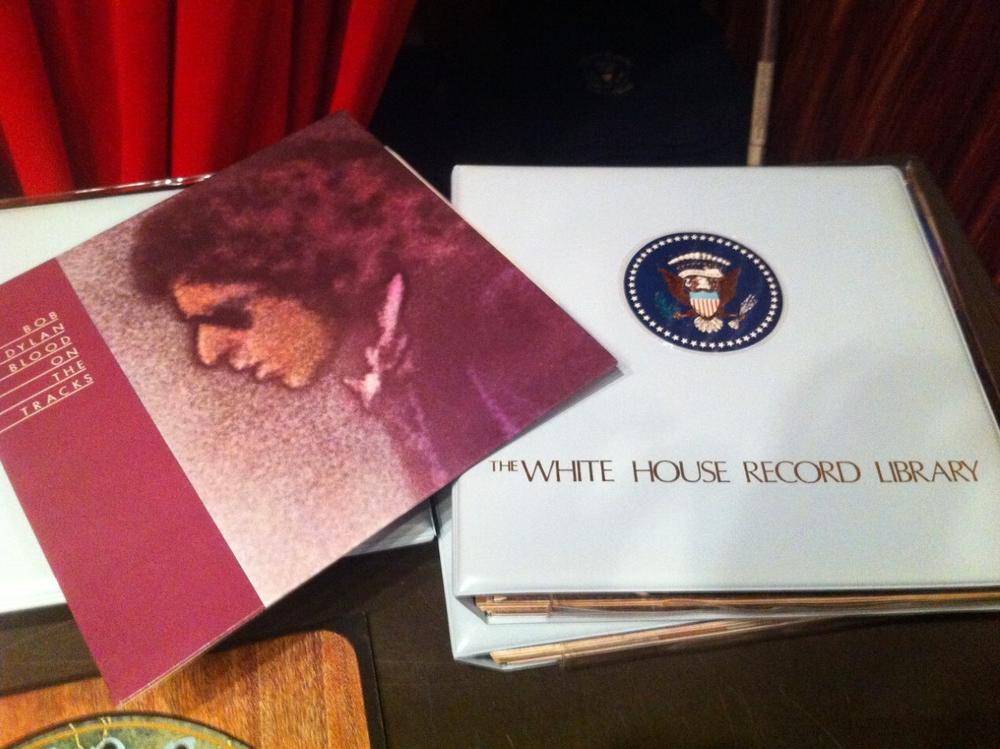

From Pat Boone to the Sex Pistols: Inside the secret White House record collection

Primary Content

Updated May 18, 2022 at 5:19 PM ET

It all started on a Carter family vacation, around 2008-09.

John Chuldenko's uncle, Jeff Carter — the son of former President Jimmy Carter — was talking about a night at the White House during his dad's administration in the late 1970s.

Uncle Jeff wasn't sure if it was a state dinner, but it "was something fancy," Chuldenko remembers him saying.

Later in the evening, presumably after the fancy dinner, Uncle Jeff snuck upstairs to the residence with a couple friends and they started playing records and "drinking wine and stuff." They were playing The Rolling Stones, specifically the song "Star Star" off their 1973 album Goats Head Soup.

The song is not rated PG, and it drew the attention of Uncle Jeff's mom, Rosalynn Carter, and then-second lady Joan Mondale. They apparently did not stay long.

Back to Chuldenko and the annual Carter family vacation, which the former president's grandson tells NPR he's pretty sure was in Florida that year. Chuldenko was intrigued by the records and wondered where they came from. Uncle Jeff blew his mind by telling him that the White House had an official record collection.

But was it true? He needed confirmation.

Shortly after the vacation, Chuldenko decided to reach out to the White House curator's office to confirm, and to his surprise, they got back to him a few days later. They confirmed the existence of the White House record collection, but said it was stored in a secure facility at a warehouse that he was not allowed to visit.

But, he persisted and requested to view the record collection at the White House, but that had to be cleared by the office of first lady Michelle Obama. It was.

Chuldenko quickly started planning the trip and reached out to some of the people who curated the collection, like jazz critic Bob Blumenthal and one of his advisers, Kit Rachlis — both of whom ultimately accompanied him to the White House later that year — just days before Christmas in 2010.

"We walk in and they're all in these cardboard boxes," Chuldenko recalls of the visit. "And it's like, whoa. Here I am in the White House, downstairs in the movie theater, digging through these records that are embossed in presidential seal binders. It is the coolest thing ever for a record collector. It is the most exclusive record library in the world, probably."

So, they start laying out their favorites, including: The Woodstock soundtrack, Neil Young's Decade, the self-titled Clash record, Elvis Costello's My Aim Is True, and Bob Dylan's Blonde on Blonde.

So, what record did they play first? One of Chuldenko's favorites: Van Morrison's Astral Weeks.

After hours in the White House screening room, someone from the curator's office came down and said it was time to go.

"We put everything back where it belonged and they came in with these dollies and they started wheeling away these cardboard boxes full of records — and I think it was at that moment when I realized, like, they're going to take this back to the secure storage facility," Chuldenko says. "No one is going to ever see these again."

Through that visit, research and interviews he learned a fair amount about this mysterious record collection. The first volume, created during the Nixon administration and presented to the first family in 1973, contained more than 1,800 LPs and featured bands from Elton John and The Doors to more easy-listening acts like Don Ho and Pat Boone.

The second volume, presented to the Carters in 1981, was a little more rock and roll and featured records from artists like Chuck Berry, Neil Young and Bob Dylan — along with some records that Chuldenko refers to as controversial.

"The first Clash record is in there, the Sex Pistols is in there," he says. "Rocket to Russia is in there from The Ramones. You got Funkadelic in there. There's some stuff that you would not expect to be in the White House record library."

What is also not in the White House record library is anything from 1980 to the present day, and Chuldenko wants to change that by updating the collection with a third volume.

Will he succeed? He just may. He has a call scheduled with someone from the Recording Industry Association of America — the folks responsible for the collection from the 1970s — on Wednesday.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.