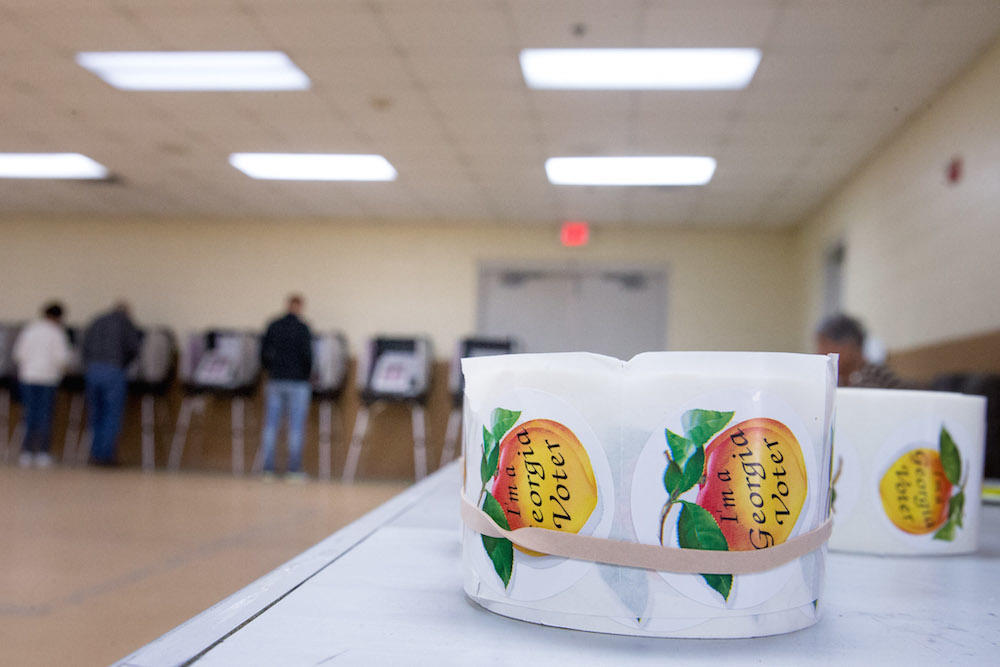

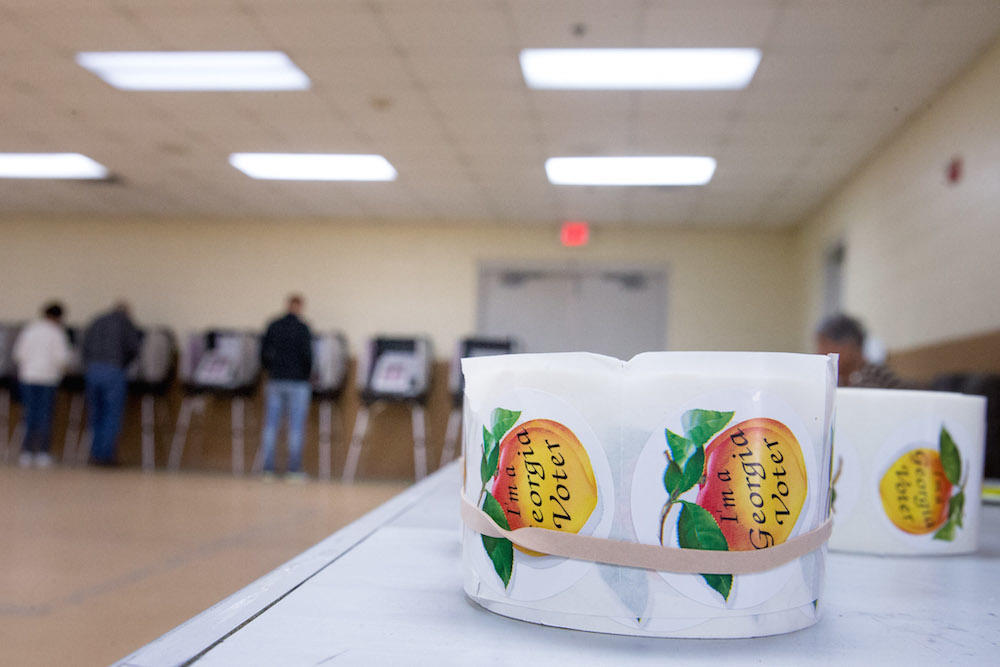

Caption

On Friday, a group of about 20 people gathered at the office of the Chatham County Board of Elections to demand recounts and voter information.

Credit: GPB file photo

On Friday, a group of about 20 people gathered at the office of the Chatham County Board of Elections to demand recounts and voter information.

Craig Nelson, The Current

In a hint of possible election crises to come in November and beyond, skeptics about Georgia’s voting systems are mounting an array of challenges in Chatham County and statewide to the outcome of the May 24 primary election.

In the span of two days last week, Jeanne Seaver asked Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger last week for a recount of ballots cast in all of the state’s 159 counties in her race for the Republican nomination for lieutenant governor. Two Chatham County Election Board candidates — Robin Greco and Jennifer Salandi — asked for a hand recount or forensic audit of the ballots cast in all of Chatham County’s 92 precincts.

Then, on Friday, a group of about 20 people gathered at the office of the Chatham County Board of Elections to demand recounts and voter information. This spate of allegations of voting irregularities were fueled by a programming mistake that caused an inaccurate vote count in a DeKalb County Commission race.

Although county and state officials have resolved that issue, the insistence that the voting process is flawed, if not rigged, endures. That has raised anxieties among many, not least Chatham elections officials and staff.

“They scared the devil out of the staff and everything else,” Billy Wooten, Chatham County Supervisor of Elections, said of the skeptics who converged on his office on Friday.

Wooten said there’s no legal basis under Georgia’s new election law for recounts or forensic audits unless the margin between candidates is equal to or less than 0.5%. The law, passed by the Republican-majority legislature, was supposed to bolster confidence in the state’s elections, Gov. Brian Kemp has said.

Some 55,201 ballots were cast in Chatham in the primary, compared to some 1.2 million statewide. But the disparity can be misleading.

The speed with which individuals and groups in Chatham have invoked a technical problem with the tally in one Georgia county to dispute the results on their own shows the extent to which voting systems themselves have become fodder for partisan controversy.

Beth Majeroni filed an open-records request asking for all ballots cast in her Chatham County precinct, where she served a precinct chairperson and poll watcher. Her demand was fueled by the computer glitch in Dekalb and her distrust of Raffensperger, who has oversight of elections.

“If a miscount can happen in Dekalb, there is a concern it could happen anywhere,” said Majeroni, co-leader of School Board Action Team, a conservative education reform group.

Majeroni is also dismayed by what she said is Raffensperger’s control over a single computer server that stores election data.

“It seems to me like the fox in the henhouse if you’re running for a position and you’re in charge of the server that gets all the votes,” she said.

Raffensperger defied Donald Trump after the 2020 presidential election and earned the lasting contempt of his supporters by refusing the president’s request to recalculate the vote count and find 11,780 votes to secure the state’s 16 electoral votes. In the May 24 primary, Raffensperger defeated Trump’s endorsee, Jody Hice, by 52.3% of the vote to 33.3% to be the Republican candidate for the Secretary of State’s race in November.

For the two dozen people who converged on the Board of Elections office last Friday, the technical issues experienced by Dekalb County were not simple glitches but another piece of evidence undermining trust in the Dominion voting system, which Raffensperger’s office also implemented in 2020.

A federal government report issued last week compounded the protestors’ exasperation. The report, issued by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, said that the voting touchscreens used in Georgia have security vulnerabilities that put them at risk to hacking attacks. There was no evidence, however, that those weaknesses had been exploited.

Sara Lain-Moneymaker, who was among the Friday group demanding recounts, believes Georgia should scrap the Dominion system altogether.

“If we’re using the same machines as DeKalb County, how can we trust that our machines weren’t messed up, too?” she asked.

Wooten, the elections supervisor, tried to reason with the skeptics, insisting that the system had, in fact, worked in Chatham without the problems in Dekalb or elsewhere.

“These folks wanted to talk about Cobb County, and I said, ‘This is Chatham County. This isn’t Cobb,’” he told The Current.

“They’re saying, ‘You can recount.’ There’s not even a provision for a hand recount in the law. The exact wording from the state said, and I quote, ‘Hand recounts are not authorized under Georgia law’” he said he told them.

Wooten further explained the way that the voting law works. Had there been a close race, there would have been a recount, as required by law, he told the frustrated petitioners. And had he detected anomalies in the vote count similar to those found by his counterpart in Dekalb, he would have gone immediately to his superiors and advised against certification until the problem was remedied. If they had evidence of voting irregularities, they should bring it to him or take it to a judge, he advised.

Still, those election skeptics who gathered in Wooten’s office were not mollified by his explanations.

Hand recounts and other measures to address voting irregularities are justified by the need to shore up confidence in Georgia’s electoral system. “If you don’t have anything to hide, why can’t they just do it?” Seaver asked.

Furthermore, they disputed Wooten’s perception that they were causing trouble.

“We were not terrifying the employees,” Lain-Moneymaker said. “Every single person in there was very respectful, very well-behaved.”

Wooten stood by his comments Monday.

“They may not have seen themselves as rowdy and unruly. But in the current atmosphere, where a person where a person can go in and shoot up a supermarket, can shoot up a hospital, can shoot up a classroom in a school, you bring a group into an office like that, and they’re loud and boisterous and argumentative, it creates a degree of anxiety and fear in the staff. They do not want to be sitting here.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current, providing in-depth journalism for Coastal Georgia.