Section Branding

Header Content

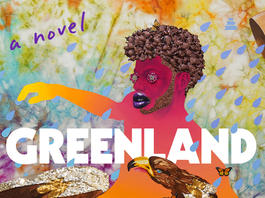

'Greenland' revives E.M. Forster — and spins a tale of racism and self-discovery

Primary Content

The British author E.M. Forster, best known for the novels Howard's End, A Room With a View and A Passage to India, was a conscientious objector during World War I. His alternative service took him to Alexandria, Egypt, where he worked for the British Red Cross. There, he met an Egyptian tram driver named Mohammed el-Adl, and began an intense relationship that violated racial and, of course, sexual boundaries.

Even after Forster left Egypt and Mohammed married, the two men kept up a correspondence, which came to a close with Mohammed's death from tuberculosis in 1922. Mohammed's widow sent Forster her husband's gold wedding ring.

In his debut novel, Greenland, David Santos Donaldson takes this crucial but necessarily closeted relationship of Forster's and runs with it, all the way from a basement room in Brooklyn to the icy white expanses of the Greenland of the novel's title. At its best, Greenland is a smart, exhilarating novel about racism and self-knowledge whose unwieldiness is compensated for by its daring.

Here's the premise: A Black, British aspiring novelist named Kip Starling has three weeks to revise his historical novel about the love affair between E.M. Forster and Mohammed el-Adl. Eleven publishers have turned it down; the only one who's sort-of interested is about to be bought out by a media conglomerate; Kip needs to sell his book before that happens. So, like some Edgar Allan Poe madman, he's hammered plywood boards across the inside door of his basement study in the brownstone he shares with his estranged husband — a white psychotherapist. Fortified by boxes of Saltine crackers, cans of coffee and 21 gallons of spring water, Kip sits before his laptop and waits for inspiration. And naps. And eats Saltines.

Kip feels a kinship with Mohammed: He, too, is in a complicated relationship with an older, wealthier, white man. Kip wants Mohammed to narrate his version of the affair with Forster, but he's having trouble with Mohammed's motivation for telling his story, as well as with his voice. After all, Kip — short for Kipling, his father's favorite writer — was raised by Bahamian parents who themselves grew up under "the full sway of British colonialism." Consequently, Kip tells us he "was raised in the same Victorian ether as [E.M.] Forster" and his own voice is more like Forster's than Mohammed's. The breakthrough happens when Kip realizes that Mohammed could feel compelled to tell his story to him, Kip. Here's Kip's epiphany:

"Just as I'd felt [a] lightning bolt of connection upon [first] seeing [a] photo of this young man who lived a hundred years ago, what if Mohammed felt an equally strong connection with his image of a man in the future? ... [A] modern black man who lives the life he can't? What if Mohammed wants to tell me about his experience so that I know, from his perspective, where we queer, Black, colonial men have come from? What if Mohammed also needs me to exist so that he knows, ... that there is a future for our kind, ... a Possibility?"

What ensues is a whirlwind of stories: Both Mohammed and Forster narrate chapters of Kip's novel-within-a-novel describing the course of their relationship; there's also Kip's present-day account of his life in New York where he's felt ostracized by African Americans because of his Brit speak and mannerisms. Midway through these reveries, Kip is liberated from his basement writing cell by supernatural voices, who command him to go to the wilderness to find his authentic self.

If these plotlines sound a little overheated, well, sometimes they are. In fact, I put the novel aside twice. But Donaldson's own ingenious voice as a writer kept drawing me back; so did his humor. There are funny riffs here on the Nowhere-ness of airline travel, MFA program posturing, and an entire chapter entitled "Long Live Idris Elba" where Kip pays tongue-in-cheek tribute to the Black British actor who's made him feel seen and understood in America.

"Only connect" is, of course, Forster's famous epigram from Howard's End, a poignant, at times desperate plea for connection among people who are as much mysteries to themselves as to others. In Greenland, Donaldson reworks "only connect" to be a paean to self-connection, the integration of ambivalent identities into something like a wryly formed human being for our time.

Copyright 2022 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.

Bottom Content