Section Branding

Header Content

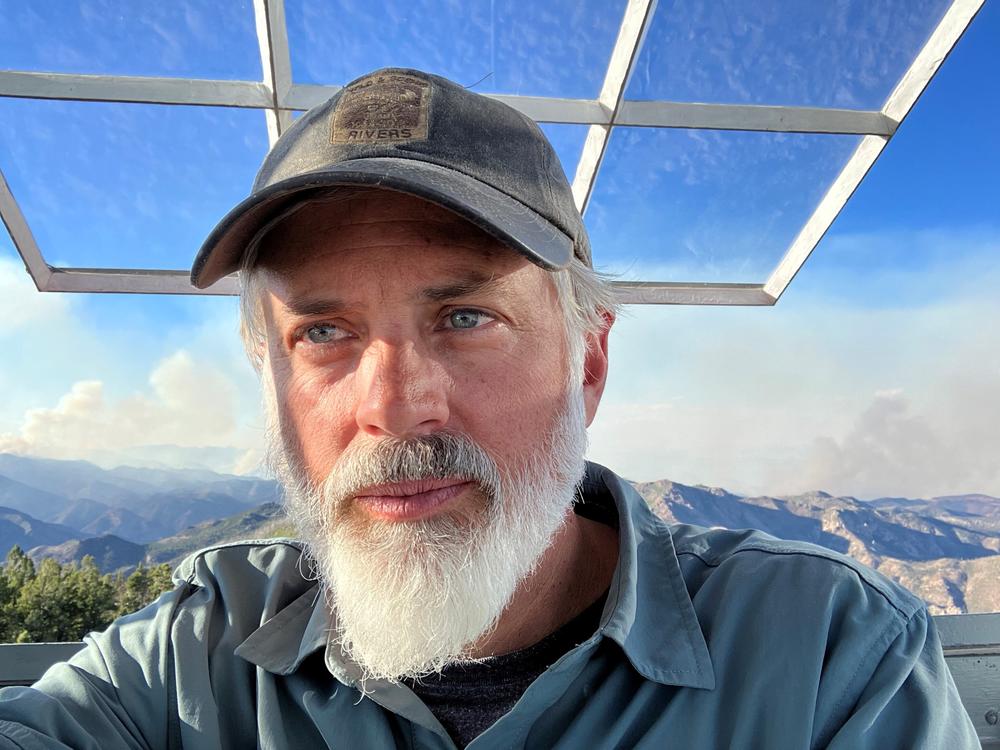

A New Mexico firewatcher describes watching his world burn

Primary Content

Updated June 22, 2022 at 7:08 AM ET

When a wildfire forced Philip Connors to evacuate in a hurry a few weeks ago, he wasn't just any fire evacuee. He works for the U.S. Forest Service as a fire lookout, responsible for spotting wildfires early.

"The essence of the job is to stay awake and look out the window and alert the dispatch office at the first sign of smoke," he explained.

His usual perch is a small room at the top of a 35-foot tower in a remote corner of the Gila National Forest, about a 5 mile hike from the nearest dirt road. It's his home for about half the year.

But when the Black Fire crept too close, he packed up his belongings for a helicopter to ferry out, and hiked out with a colleague, his relief lookout who helped him pack.

"I'm not ashamed to admit I hugged a few trees before I left, some of my favorites," Conners said. He described how the mix of trees changes depending on elevation, from a mix of conifers intermingled with aspen at the highest elevations, to a belt of ponderosa and oak, then pinyon pine and juniper.

Connors, who is also a writer, deeply loves the forest he has watched over every summer for the past 20 years. But it was a different forest two decades ago, and will be even more changed once the flames die down.

At first, he thought of the lookout job as a paid writing retreat with good views. But over time he became a witness to the changes brought on by a warmer, drier climate.

"The place became my citadel and my solace. And it's given me so much joy and beauty over the years," he said. "Now it's almost like the tables are turned, like it is in need of solace because big chunks of it are being transformed and going away."

He notices the signs everywhere. At the highest elevations, the oldest conifers used to be snowed in through late March. Now there's less snow, and the soil is drier.

When he hiked up the mountain for the first time this spring to open the tower, "with every footstep I was sending up little puffs of powder from the soil," he said. "I had never seen that this time of year."

The Black Fire started on May 13, and Connors watched it grow into a megafire.

"It was kind of an exercise in psychic disturbance, to live in the presence of this thing that I felt certain would eventually force me to flee," he said. "Even at night, you start dreaming about it because it's just this presence lurking on your horizon. Then I would climb the tower after dark and have a look. Seven, 8, 9 miles of my northern horizon would be glowing with fire."

After his regular lookout was evacuated, he was moved to another where the fire had already burned over.

Connors said the spruce, pine and fir forests at high elevations are vanishing from his part of the world.

"My arrival in this part of the world coincided very neatly with the onset of the worst megadrought we've seen in more than a thousand years," he said.

The Gila Wilderness will never be the same for the Gila trout, salamanders, pocket gophers, tree frogs, elk, deer and black bears, or for Connors. But he'll observe the burn scars and how the forest heals. He says his responsibility is to "see what it wants to become next."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.