Section Branding

Header Content

Colombia's tribunal exposes how troops kidnapped and killed thousands of civilians

Primary Content

BOGOTÁ, Colombia — In front of a war crimes tribunal, Blanca Monroy took the microphone and addressed the former Colombian army officers who were responsible for killing her son. He was an unemployed carpenter who, in 2008, was kidnapped, shot 13 times and was then buried in a mass grave.

"No one understands the pain of a mother who loses her son. It's an emptiness that will never, ever, be filled," she said. "You should ask God for forgiveness."

Monroy's son died in one of the darkest chapters of Colombia's 50-year guerrilla war. To run up body counts, Colombian soldiers kidnapped and executed more than 6,400 civilians from 2002 to 2008 and falsely reported them as Marxist guerrillas killed in combat, a special tribunal found.

The killings, known in Colombia as "false positives," were never fully investigated by Colombian courts. But now the tribunal, set up under a 2016 peace deal, is trying to get to the bottom of what happened. And it could result in a former high-ranking officer in the country's U.S.-backed military being convicted of war crimes.

This comes as Colombia's Truth Commission is about to release its final report, documenting accounts from people affected by the long civil war.

There was pressure to pump up body counts

Formally known as the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, the tribunal functions outside of Colombia's regular judicial system and has a 15-year mandate to prosecute the most heinous crimes committed by guerrilla fighters and the government troops they fought against. The tribunal started work in 2018 by investigating thousands of kidnappings carried out by the rebels, but it has now moved on to abuses committed by the armed forces.

Most of the false positive killings took place in the 2000s, when Colombian military officers came under fierce pressure to crush the guerrillas. Failure could derail their careers. However, reporting bigger body counts could mean promotions, overseas postings and other benefits.

"There was constant pressure from our superiors, including the army commander, to produce combat deaths," former Lt. Col. Álvaro Tamayo, one of the defendants, told a war crimes tribunal hearing in April in the northern town of Ocaña, where many of the false positive killings took place.

"'Good' officers produced bigger body counts. 'Bad' officers didn't," he said. "This generated psychological pressure and fear of being demoted or expelled from the army for a lack of operational results."

So, some officers hatched a lethal conspiracy.

They lured poor, unemployed young men from Bogotá and other cities to small towns near the war zone with promises of jobs. Then, according to testimony gathered by the tribunal, soldiers gunned them down, planted weapons on them, dressed them in camouflage and reported these innocent civilians as rebels killed in combat.

Officers can avoid prison

The tribunal's estimate of false positives goes far beyond previous tallies. And the tribunal's president, Eduardo Cifuentes, says the real number could be even higher than what investigators found. He tells NPR the killings are "the absolute worst" of Colombian war crimes.

The top priority of the tribunal is to learn exactly how and why the crimes happened. The goal is to make sure they never happen again and to help the country heal after decades of warfare.

"Our objective is reconciliation," said tribunal judge Alejandro Ramelli, speaking at the Ocaña hearing. "But you can't forgive if you don't know what happened."

That's why the tribunal is being lenient with defendants. They can avoid prison if they confess to and fully explain their crimes, including who gave the orders. They're also required to make up for some of the harm they've caused and participate in public hearings held in former war zones where the crimes were documented.

Mothers want false positives' names cleared

The hearing in Ocaña took place in a local university auditorium where a dozen defendants, now stripped of their military uniforms, sat stiffly onstage and heard directly from the relatives of their victims.

When it was her turn to speak, Zoraida Muñoz faced the former army officers and insisted that it made no sense to target her 22-year-old son, who was himself a former soldier.

"I want my son's name cleared," she said. "He was no guerrilla. He'd just gotten out of the army. But he was abducted and killed."

The defendants include a retired general who stands to become the highest-ranking former officer convicted of war crimes. They all sounded deeply repentant. At one point, former Lt. Col. Tamayo admitted that he gave the direct order to execute several innocent civilians on the outskirts of Ocaña.

"I betrayed my family and the army," Tamayo said, his voice breaking. "I am a disgrace."

Sandro Pérez, a former army sergeant, was even more blunt, saying, "I became an assassin, a monster for society, a death machine."

Not all Colombians are on board with the tribunal

The testimony has been riveting. But critics in the right-wing political and military establishment claim it could hurt army morale and damage the institution. They insist that the tribunal should stick to investigating massacres and kidnappings carried out by the guerrillas and that it is placing far too much blame for war atrocities on government troops.

President Iván Duque, a conservative who opposed Colombia's peace treaty, tried in 2019 to overhaul the tribunal and strip it of some of its powers, saying, "we can reform and design a [court] that assures genuine truth and justice to all Colombians." But that effort failed.

Some critics accuse the tribunal of exaggerating the scope of army atrocities.

"What we are seeing is the case of a few bad apples," says John Marulanda, a former army colonel who heads a national association for retired military officers. "You cannot generalize and say 'all the army is involved.' "

He thinks military judges or the country's ordinary justice system should handle the false positives cases. However, 15 years after the army killings were first revealed by human rights groups and mothers of the dead, there have been only a handful of convictions.

Testimonies show the killings were carefully coordinated

This so-called "impunity gap" justifies the efforts of the war crimes tribunal to revisit the cases, says Rodrigo Uprimny of the Bogotá human rights group Dejusticia. What's more, he says the testimony makes it clear that the killings were carefully coordinated and not the work of just a few out-of-control troops.

"When you see a colonel saying 'I did that, I did that, I did that,' really confessing systematic crime in public view, it's really very powerful," he says.

Accused soldiers who fully cooperate with the tribunal will not go to a traditional prison, though their freedom will be restricted. They'll also spend up to eight years performing community service in the neighborhoods of their victims.

At first, that didn't sit well with Blanca Monroy, who spoke at the Ocaña hearing and whose son, Julián Oviedo, was shot 13 times.

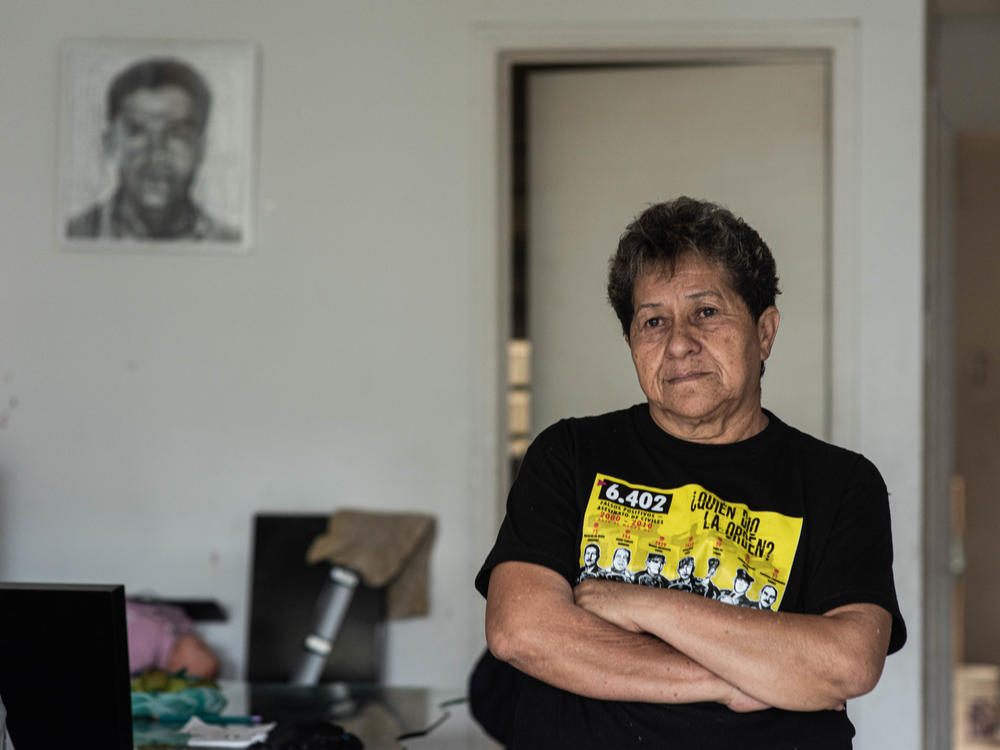

"I was thirsty for justice and I wanted them put in jail," she says, speaking from her modest home in Bogotá.

But the war crimes tribunal allowed her to meet face to face with the men responsible for her son's death. She rebuked them. She cried with them. Gradually, she says, she even began to forgive them.

"I no longer feel fury or hatred," she says. "Now I feel at peace."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.