Section Branding

Header Content

How Elizabeth Cotten's music fueled the folk revival

Primary Content

As a Black woman playing fingerstyle guitar, Yasmin Williams has been hailed as a "hero for a new generation." She says she often felt like an anomaly- until she discovered a YouTube video of Elizabeth Cotten.

"I knew about Sister Rosetta Tharpe and other kind of more rock and roll or electric players and singers and I loved them too, but just seeing an acoustic guitarist was amazing." But when Williams tried to learn more about Cotten she discovered that most accounts of her life skipped over the hardships she overcame, focusing only on her late-career success.

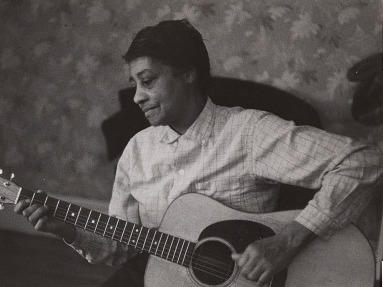

Cotten was born in Chapel Hill, N.C. around 1893. Her father worked in the mines. Her mother cleaned houses. When Cotten's brother was off at work, Sis Nevills, as she was called then, snuck into his room and took his guitar off the wall. Since she was left-handed, she turned it so the bass strings were at the bottom, therefore "backwards." She used her thumb to play the melody and her fingers for the low notes.

When Cotten's brother discovered her playing, he tried to offer advice, "'You got it upside down, turn it around or change the strings." She tried but liked the sound better the other way, so she kept with it, practicing for hours on end. After the third grade, Cotten left school to work. Making 75 cents a month cleaning houses and cooking, she saved up to buy her guitar. Cotten picked up new songs after hearing them only once or twice, and wrote her songs, including "Freight Train."

Cotten was married in her mid-teens and had a daughter. A pastor discouraged her from playing "wordly" songs. But by the mid-1940s she had left the church and her marriage and she was living with family in Washington, D.C. when she applied for a job at a local department store, where she was hired to sell dolls. When a girl wandered away, Cotten saved the day by reuniting her with her mother. She didn't know it, but that woman was composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, wife of ethnomusicologist Charles Seeger, and mother to budding folk musicians Mike and Peggy, and stepson Pete- who was well on his way to stardom as a member of the Weavers.

The Seegers hired Cotten, whom they called "Libba," to cook and clean and look after the kids. They were surprised to discover that she was a musician, too, says Peggy Seeger. "When I was about 15 I walked into the kitchen and I saw her playing the guitar that was hanging on the wall. And she was playing 'Freight Train.' Then she started trotting out songs. She knew a lot of songs. We would have been happy to do the cooking and cleaning if she would just play!"

In 1956, 21-year-old Peggy took Cotten's "Freight Train" to England. "Skiffle was kind of at its height," Seeger recalls. "I arrived in March of 1956, and I was the flavor of the month because I was female, I was American, I was young, I played guitar and banjo, and I was footloose and fancy-free. So, I just sang wherever anyone asked me to sing and I even sang in places they didn't ask me to sing."

"Freight Train," which Seeger also recorded, sounded traditional, even timeless. She says it was picked up very quickly by other artists. "I taught it to Nancy Whiskey and Charles McDevitt, and when I went to China in 1957, they were playing it around the coffee houses."

The "folk process," a term coined by Charles Seeger, holds that performers can add something new to old songs (altered lyrics, different arrangements) that transforms them into distinct compositions. A common practice among musicians of the era, the Chas McDevitt group released their version of "Freight Train" in 1957, which they copyrighted under the names "Fred James and Paul Williams," pseudonyms for McDevitt and his manager, Bill Varley.

Legal theorist Kevin J. Greene says copyright law often disadvantaged the Black artists whose music was the foundation of the folk revival. "A lot of times these artists, not being well educated, not being well resourced, not knowing how to navigate the copyright system, didn't realize that if they performed their work publicly anybody could fix those lyrics and claim copyright."

The song shot up to No. 5 on the UK charts, then Rusty Draper took it to the Top 10 in the U.S. where promotional materials described the song as "a new hit tailor-made for him." When she learned of the infringement Cotten assigned rights to a music publisher who initiated legal action.

According to her family, an out-of-court settlement gave Cotten only a third of the songwriting credit to be shared with McDevitt and Varley. Though the royalty terms were never made public, at the time it was customary for music publishers to take a 50% cut, likely leaving Cotten with only a fraction of the song's true worth. Meanwhile, other artists continued releasing "Freight Train," including Peter, Paul and Mary, who rerouted the song to New York City in 1963. With a lyrical shout-out to Bleecker Street, they credited the song to Paul Stookey, Mary Travers, Elena Mezzetti and producer Milton Okun.

Mike Seeger started coming by Cotten's house to tape her performing "Freight Train" and other songs. He produced her debut album Negro Folksongs and Other Tunes (later renamed Folksongs with Instrumentals and Guitar) for release on the Folkways label in 1958. However, efforts to reclaim "Freight Train" were confounded by the appearance of the Chas McDevitt Group on The Ed Sullivan Show. The song became such a hit, that McDevitt even opened a coffee bar in Soho called Freight Train.

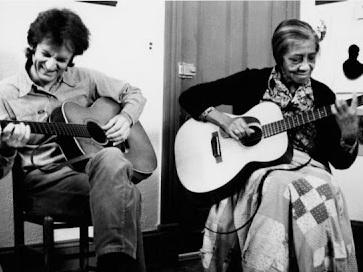

Cotten and Mike Seeger maintained a close lifelong friendship, and she continued to record and tour with him over the years, and appear at high-profile events such as the Newport Folk Festival. When she wasn't cleaning houses or performing, Cotten shared a modest room with her great-grandchildren, says Brenda Evans.

"Every night she would play to us and one of those evenings she liked the little tune she was playing and granny said to us, 'Well, kids, can you all think of some words to go to this song?' So all of us just started piping in, and that's how 'Shake Sugaree' came about."

12-year-old Evans also sang on the recording, which was copyrighted and released in 1966. Fred Neil nevertheless claimed a co-credit for his retitled arrangement, and in 1969 Pat Boone's renamed version identifies Neil as the only songwriter.

Bob Dylan, the Grateful Dead, and Joan Baez were among the artists who performed Cotten's songs live, but they didn't always announce them as covers.

Culture critic Daphne A. Brooks says generations of Black women musicians were denied the spotlight, and the world was denied their art. Cotten didn't leave domestic work until she was nearly 80 years old, at about the same time she received the 1972 Burl Ives Award for her contributions to folk music. It wasn't until 1984 that Cotten was recognized as a National Heritage Fellow by the National Endowment for the Arts. The following year, she won her first and only Grammy, for Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording.

Since her 1987 death, Cotten has been recognized by North Carolina and New York, where she lived in her final years. This year the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is inducting Cotten as an "early influence." Like other Black women guitarists, such as Etta Baker, Algia Mae Hinton, and Memphis Minnie, her influence has reverberated through the generations, permeating every genre of music. "It's in the soil of our sonic landscape," says Brooks.

"The brilliance of Elizabeth Cotten's music is the music of a Black girl's lifeworld, a Black girl prodigy that wrote songs, who composed music and innovated her own unique style of playing," adds Brooks, noting that "it's a specific manifestation of her own North Carolina Jim Crow era Black girl desires, hopes, dreams, and struggles."

Singer-songwriter Laura Veirs, who published a children's book, Libba, in 2018 credits the Seegers for exposing Cotten's music to the world, but says "it was her determination that gave the world her voice." Looking back, Peggy Seeger agrees, "She was her music. When she started to play, she wasn't 'the help.'"

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.