Caption

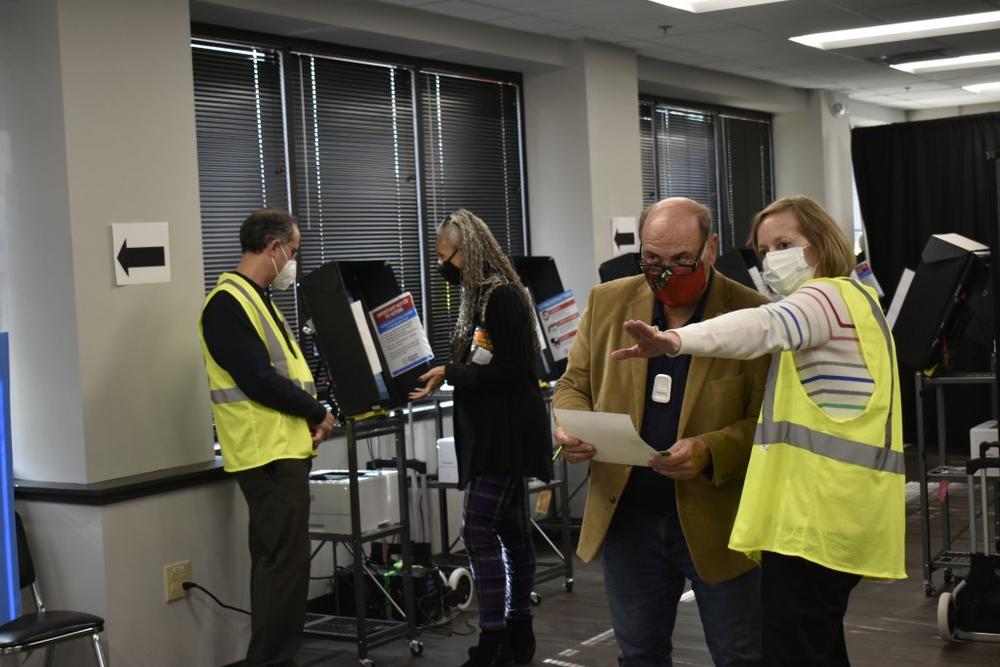

In Georgia, the Legislature gave the Georgia Bureau of Investigation authority to investigate election crimes and issue relevant subpoenas. Cobb County poll workers helped voters cast ballots in 2020.

Credit: Ross Williams/Georgia Recorder