Caption

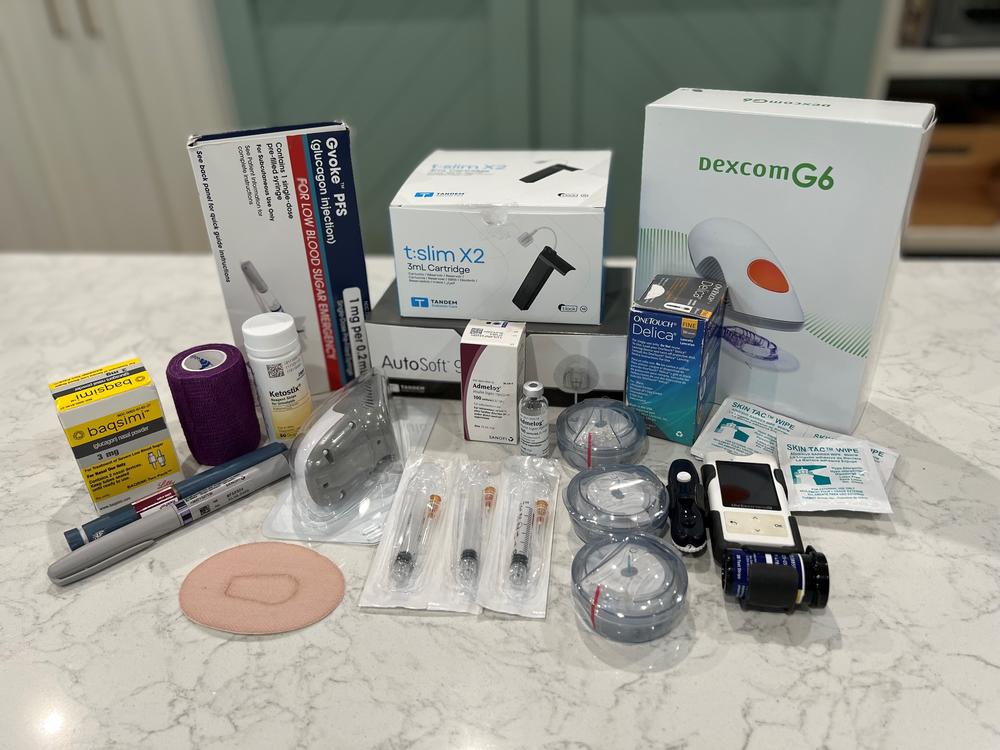

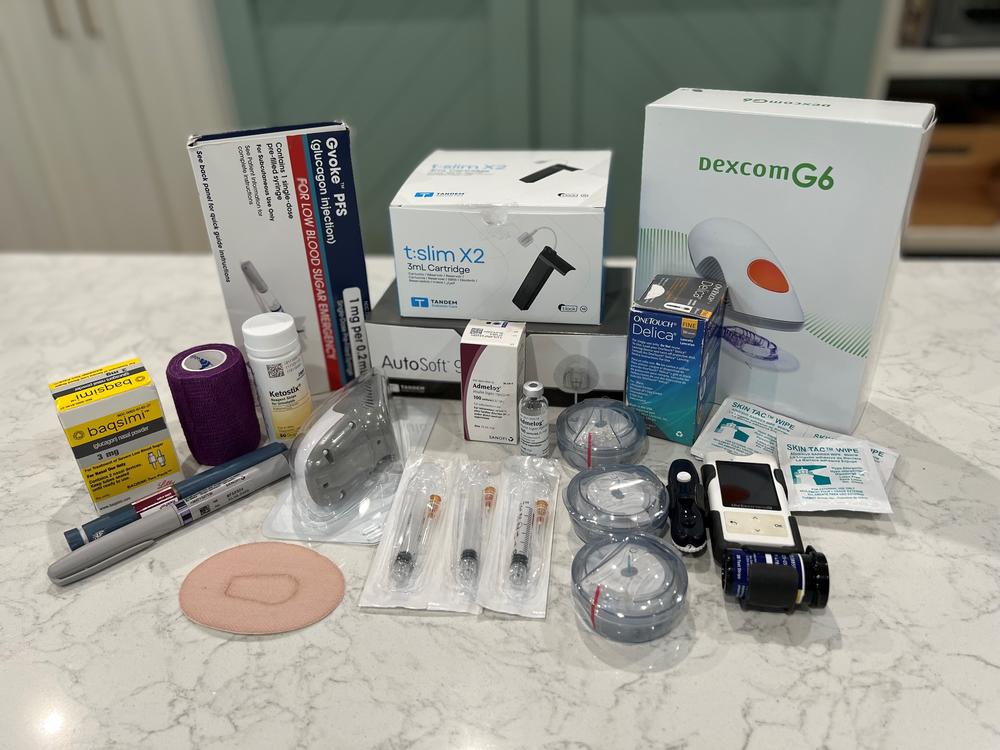

Teresa Acosta displays the diabetes supplies that her 13-year-old son Bauer relies on day to day.

Credit: Courtesy of Teresa Acosta

When 13-year-old Bauer Acosta wakes up in the morning, he goes through a crucial routine.

“I check my blood sugar and if it's high at all, I make sure my pump hasn't run out of insulin or died,” he described.

Before breakfast, he doses insulin about 20 minutes ahead of eating, based on what he’s having. After that dose, he can’t change his mind from cereal to eggs.

Acosta is diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, a chronic condition that makes his days different from other teenagers. When he goes out to hang with friends, he keeps a bundle of Starburst candies in his pocket just in case he needs a boost to his blood sugar levels. While on family vacation at the beach, he takes doses of insulin before going in the water.

“When it goes too low, sometimes my head hurts; sometimes I just feel really tired and dizzy,” he said. “And when I'm high, I just feel sick.”

Bauer is one of around 1 million people in Georgia, roughly 12% of the state's population, that has diagnosed diabetes, according to the American Diabetes Association.

Diabetes is caused when an individual’s body either does not make enough or doesn’t properly use insulin to manage blood sugar levels.

The result is a minute-by-minute lifestyle where, diabetics say, even a trip to the grocery store can go wrong if blood sugar hikes too high or dips too low, and insulin is their life line.

Insulin has become the poster child for health care disparities between those who can afford their life-saving medication and those who cannot.

With no federal regulations to keep costs down, the drug can range between $200 and $500 per person per month with insurance.

Democrats in Congress have made capping costs a legislative priority, but convincing other lawmakers how vital insulin's affordability is to American families remains a struggle.

Bauer’s mother, Teresa, has a morning routine similar to her son's. An app on her phone keeps a constant eye on her son and constantly tracks his blood sugar levels. He dips a little low around midnight, she said, which is normal. But if anything seems off, she wakes him up to check his pump.

Her son was diagnosed with diabetes when he was 6 years old — a day that changed their lives forever.

“It was just this kind of constant state of worry — not sleeping at night,” said Teresa, a single mother of three. “The second he would get sick, it would be, 'Is this going to turn into something really serious that puts us in the hospital?'”

The price for manufactured insulin in the U.S. is more than ten times what diabetics pay in other countries, costing American families like Acosta's too much.

In March, House lawmakers passed The Affordable Insulin Now Act, which caps out-of-pocket costs for insulin under private health insurance and Medicare at a maximum of $35 per month.

The proposal has since been tacked onto a larger bipartisan bill being negotiated in the Senate.

Democratic lawmakers at the federal level have hit a wall on major health care initiatives such as Medicaid expansion. The stakes of passage for other more focused items like insulin costs are particularly high for vulnerable incumbents in Congress such as Rep. Lucy McBath and Sen. Raphael Warnock, who have championed the proposal in their respective chambers.

Other high-profile Georgia Democrats, too, have made insulin prices a key component of their general election campaigns. Gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams penned her own three-part plan that provides an emergency one-month supply of insulin for qualifying Georgians.

But while advocates stress the importance of capping out-of-pocket costs of insulin, it’s widely recognized that the plan doesn’t go far enough and leaves diabetics who lack health insurance on the hook for even higher prices determined by the will of manufacturers.

“We're just talking about this one particular battle,” said Liz Ernst, with Protect Our Care Georgia. “It is a critical first step that will deliver relief for millions of families struggling to pay for this life-saving medication.”

Georgia Democrats pushing for the $35 cap cheered when the proposal was included in a Senate bipartisan plan introduced in June after months of negotiation.

The INSULIN Act — sponsored by U.S. Sens. Jeanne Shaheen, a New Hampshire Democrat, and Susan Collins, a Maine Republican — is supported by chamber leadership.

But the bipartisan bill needs at least 60 votes to pass — a tall task in an evenly divided Senate that has hit a stalemate on most major issues.

McBath’s legislation passed by the House in March had the support of 12 Republicans, but a majority of the party still voted against it.

Teresa Acosta displays the diabetes supplies that her 13-year-old son Bauer relies on day to day.

When the pandemic hit, Acosta's mother, Teresa, lost her job at the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Up until that point, she was paying $90 a month for her son's insulin and hundreds for diabetes supplies on employer-sponsored coverage.

“Health care was expensive before,” she said. “But with Bauer’s diagnosis, it took it to a level. It created a lot of fear just financially for me, but then also for his future. How was he going to live his life with this kind of anvil on his back?”

Since she lost her job, Teresa has relied on the state’s PeachCare program for her children’s insurance which covers all of the out-of-pocket costs — but not without a different price.

“The downside is that I find it really, really difficult to find doctors that will see my kids with that plan,” she said.

In March 2019, Teresa met with then-freshman congresswoman McBath in her office in Washington, D.C.

“I got to explain what the burden of diabetes is for my family,” she remembered. The meeting spurred McBath’s advocacy for a cap on insulin costs.

For families living with diabetes, there are a lot of unknowns, Teresa said, from insulin costs — which are renegotiated yearly by drug manufacturers and insurance companies — to whether or not they will even have health insurance.

“Just having that knowledge that no matter what, my son is covered and can live,” she said, “that would be tremendous."

When Dr. Kate Wheeler visits with diabetic patients, the Atlanta endocrinologist said much of the conversation surrounds whether or not they can afford their medicine that month. She said she rattles off a list of questions:

“Can you get your medicines? What kind of cost? Can I help you apply for patient assistance or have you used a coupon?”

About half of Wheeler’s patients are diabetic and about half of those rely on insulin. Many take a combination of insulins, she said, that can total up to around $300 a month.

Especially for Type 1 patients — who are often young adults starting out in their careers — a cap on out-of-pocket prices would be “life-altering,” she said.

The financial burden may not keep them from paying rent, buying a house or saving for retirement, as it does currently.

“It’s just so hard when you're supporting someone with a chronic disease or they don't get a break from it anyway, and then to have such a price tag to it,” she said. “It's just so hard to convince them that this is worth all their effort.”

/

Atlanta Dr. Kate Wheeler describes living with diabetes

Brooks Bellman, 28, has been diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes for more than a decade. He said living with the disease is like a full-time job.

“Day-to day, you're getting up and you have to make the conscious choice to keep yourself alive with every decision you're making,” he said.

But Bellman sees himself as one of the lucky ones.

Except for a brief period when his parent’s insurance lapsed during his teenage years, he has been able to consistently access and afford his insulin prescription.

But, like many others who can’t afford or have lapses in their insurance, he knows what rationing the life-saving drug is like.

Last year, Bellman’s doctor didn’t update his prescription for his continuous glucose monitor, which makes it easier for him to track his blood sugar levels. His insurance company didn’t get the updated information and wouldn’t issue him a new one.

Bellman spent hours on the phone over the course of a month trying to get the device.

“Stuff like that can happen because everything has to be working on all cylinders and all it takes is for one breakdown for then — poof! — you just don't have something that you kind of need for your day-to-day life to be as normal as possible,” he said.

Rep. Lucy McBath, Ga., flanked by Rep. Dan Kildee, D-Mich., left, and House Majority Whip James Clyburn, D-S.C., speaks to reporters about a bill to cap the price of insulin, at the Capitol in Washington, Thursday, March 31, 2022.

Patients and advocates see capping out-of-pocket prices for insulin as a good first step, but recognize it still leaves uninsured Georgians without reprieve.

“Everyone in the world [with diabetes] needs insulin,” Bellman said. “So the fact that we have had an internal process going wrong means that we are now being — you know, price gouging — forced to pay exorbitant costs is like the definition of kind of being exploited.”

But even the bipartisan insulin bill is on thin ice.

Although Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer indicated before the July 4 break he wanted to bring the deal to a vote, a group of Republicans have pushed back.

Five GOP lawmakers have requested that the bill go through the committee process, in which experts can weigh in on the proposal.

“This is not a friendly move on the part of those five Republicans — and it does not bode well for the bill being able to garner 60 votes, which would be necessary to pass the bill,” said David Mitchell, founder of Patients for Affordable Drugs Now — a bipartisan group that advocates for lower prescription drug prices.

Mitchell said to have the biggest impact, the cap on out-of-pocket costs should be coupled with an overall lower of list price because the additional costs shifted to insurance may lead to higher premiums.

“Insulin is like water," he said. "For people who have Type 1 diabetes and for many people who have Type 2 diabetes, they need it to live. It is critical that insulin be made available to all who need it at prices that they can afford. That is why passing a bill to lower out of pockets and lower the prices of insulin is so critically important.”