Section Branding

Header Content

Shinzo Abe's assassination spotlights Unification Church links to Japan's politics

Primary Content

TOKYO — Japan's former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was an improbable target, and his assassination on July 8 was a bizarre and shocking twist of fate for the nation's longest-serving prime minister and a well known global diplomat.

The assassination has focused public attention on the religious movement that was apparently the target of the alleged assassin's hatred — and its decades-old ties to Japan's leaders and ruling party.

The original target was reportedly Hak Ja Han Moon, the head of the Unification Church and widow of its founder, the Rev. Sun Myung Moon. The self-proclaimed messiah and "true father" of his followers, Moon founded the Unification Church in South Korea in 1954.

Japanese media have reported that the alleged assassin, 41-year-old Tetsuya Yamagami, told police that he held a longstanding grudge against the church because his mother had donated more than $700,000 to it, bankrupting the family.

He allegedly had plans to target members of the church, including the head, but switched his focus to Abe instead after viewing a video message Abe had made at a virtual church-linked event last September.

Abe did not belong to the church. But like other Japanese politicians, he had made appearances at church-related events, including last September's, where former President Donald Trump also spoke.

Renewed scrutiny on the church's role in Japan

The church immediately distanced itself from the assassination. Tomihiro Tanaka, president of its Japan branch, officially known as the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, told a press conference that Yamagami was not a member of the church, but his mother was.

"As for the motive for suspect Yamagami's crime, and the donation issue reported by the media," Tanaka said, "we'd like to refrain from discussing it, as the case is under police investigation."

On Wednesday, Yamagami's mother told investigators that she felt sorry for having caused trouble for the church. "To her, the Unification Church is everything. It is life itself. She thinks nothing about her son," another relative was reported as saying.

The Unification Church has longstanding links to Japanese politics

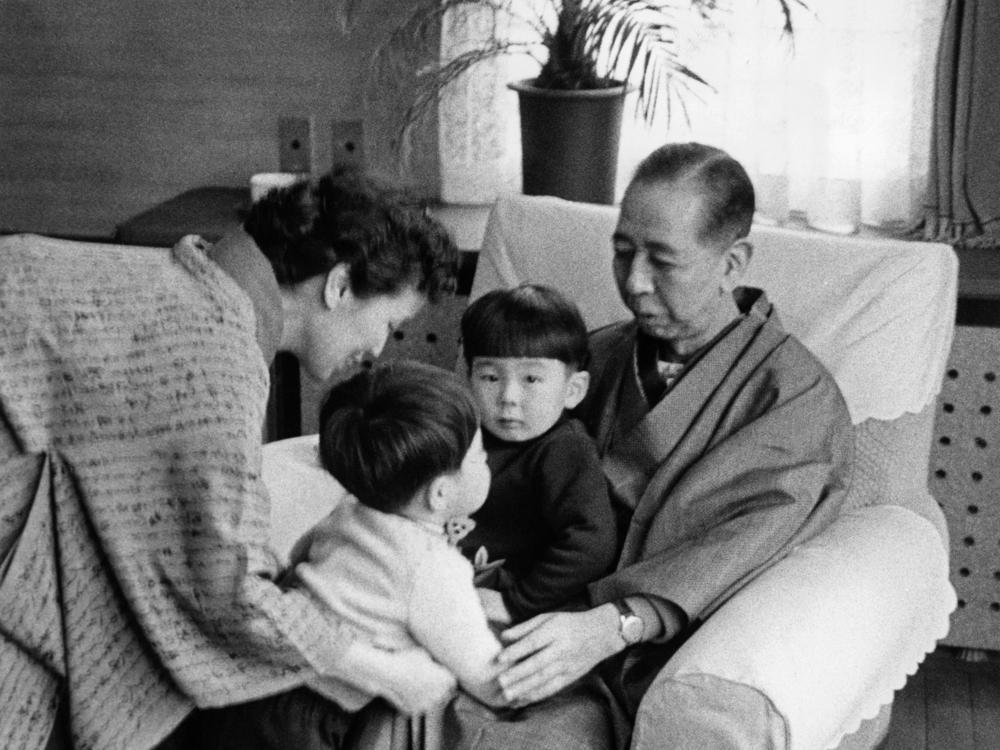

Abe's ties to the church go back generations, including his father Shintaro Abe, and grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi.

At the end of World War II, his grandfather was jailed as a suspected war criminal. In prison, Kishi contacted other right-wing nationalists, including businessman and politician Ryoichi Sasakawa.

When the Rev. Moon created an anti-communist group in South Korea in 1968, he made Sasakawa honorary chairman of its Japan branch — whose headquarters were located on a plot of land next to Kishi's residence.

"They established the Federation for Victory over Communism and Kishi supported it," says Hiromi Shimada, an expert on religion at Tokyo Woman's Christian University. "And this situation laid the foundation for Abe's assassination."

The church has long provided volunteers to help Abe's Liberal Democratic Party at election time, Shimada says. And while LDP politicians haven't been able to completely shield the church from lawsuits or criticism, they have turned a blind eye to allegations against it, he says.

Japanese Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi — who is Abe's brother — said this week that Unification Church members had volunteered in his own past election campaigns. And the head of Japan's agency investigating security lapses in Abe's killing told reporters that he headed the executive committee for a church-linked event in 2018.

The church has faced a series of lawsuits and bad publicity

Despite the current burst of public attention, the Unification Church, like other new religions, has lost influence since its rise in popularity during Japan's period of rapid economic growth in the 1960s.

"It was a time of urbanization, which produced many new believers," explains Shimada. "Now that period is over. The believers are aging, and not many new ones are joining."

The church's anti-communist mission lost relevance with the end of the Cold War, he says. A string of lawsuits against the church also dented its popularity.

Former church members say they were conned

A former church member who goes by the pen name of Fumiaki Tada, because he says the church targets its critics, claims the church duped him into joining as a student. He says their representatives withholding their true identities for months, and says they brainwashed him and then conned him out of his money.

"They plant fear in you, saying that you are full of sin and corrupted, you will end up in hell, and your family will face a similar fate," he says.

In addition to the sins of Adam and Eve, Tada says, church members are taught about the sins of Japan's colonial rule over Korea from 1910 to 1945.

But the church also offered followers a path to salvation.

"We were told that we must make up for it with money," Tada says. "So to the church's South Korean headquarters, the Japan branch is their wallet."

Tada later became a church official in the city of Sendai. He says that church headquarters in South Korea sent fundraising quotas for branches, sub-branches and individual followers to meet. Followers who could not meet the quotas, he says, were often told to borrow money to contribute to the church.

Tada says his family eventually compelled him to leave the church. His successful lawsuit against the church helped him come to grips with his ordeal and share his experiences with fellow plaintiffs.

But that's an opportunity he says Abe's suspected killer never had.

"He was the child of a believer, and he had nobody to talk to," Tada says. "This is one of the reasons he committed the crime, and I feel sorry for that."

Chie Kobayashi contributed to this report in Tokyo.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.