Section Branding

Header Content

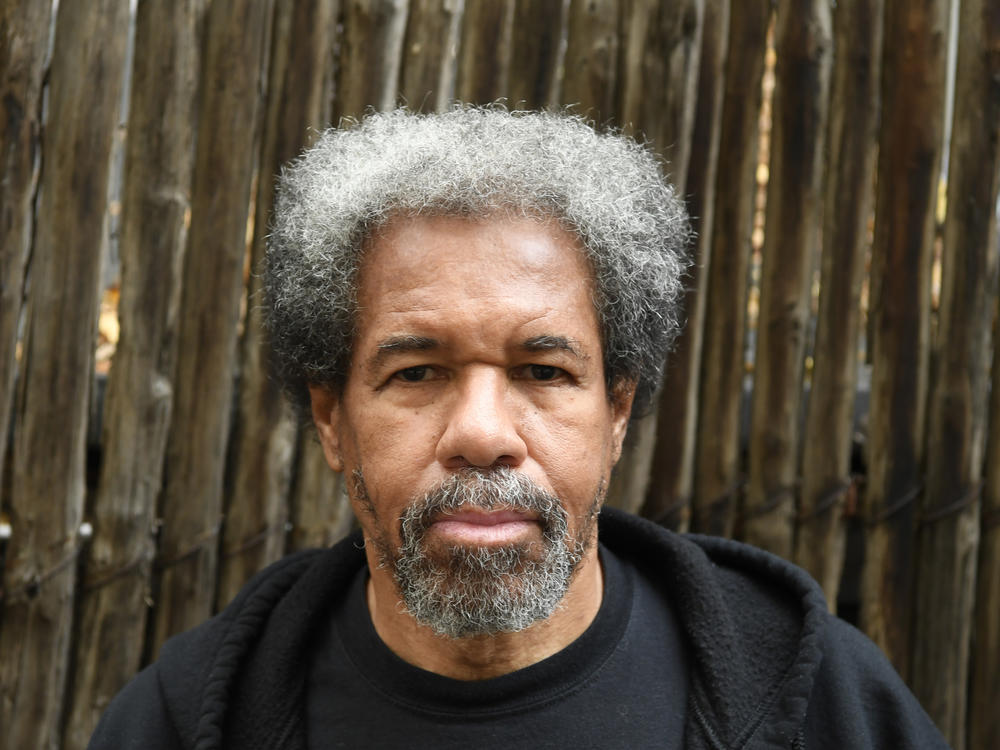

The Angola 3's Albert Woodfox, who survived decades of solitary confinement, dies

Primary Content

Albert Woodfox, who spent nearly 44 years in solitary confinement — thought to be the longest in U.S. history — died Thursday from coronavirus-related complications, according to his family.

He was 75.

In 1965, Woodfox was incarcerated at the Louisiana State Penitentiary on armed robbery charges. Woodfox and the late Herman Wallace were convicted of the 1972 murder of Brent Miller, a corrections officer, but had long maintained their innocence.

The prison sits on a former plantation known as Angola and Woodfox, Wallace and another inmate, Robert King, became known as the "Angola 3" for the immense length of their solitary confinement.

Amnesty International and other advocacy groups believed the Angola 3 were targets of mistreatment because of their Black Panther Party efforts inside the prison.

Woodfox spent the next 43 years inside a 6-by-9-foot cell for 23 hours per day, enduring claustrophobia, gassings, beatings and other forms of torture.

"Well, gas was a standard form of weapons that the security people used. So anytime you challenge inhumane treatment or you challenge unconstitutional conduct, they would gas you," he told NPR's Scott Simon in a 2019 interview.

"And depending on the severity of the confrontation, they would open up your cell, and they would come in and beat you down and then shackle you and bring you to the dungeon, and you probably would stay there a minimum of 10 days," he added.

Woodfox is remembered for his optimism and resilience throughout those many years of torture.

He spent his time educating himself and others. He taught fellow incarcerated people how to read and played games with them.

He also refused to stay silent. Woodfox protested and organized strikes on the prison's deplorable conditions, racial injustice and exploitative work hours.

"I spent a lot of time reading, writing — self-education. I used the time to teach myself both criminal and civil law," Woodfox said.

"And we lived on what we call an organized tier along the principles of the Black Panther Party, developing unity among the other guys on the tier. We taught guys how to read and write, which I think was my greatest achievement," he said.

Woodfox said the strength and determination his mother instilled in him kept him going. Having Wallace and King as not only his comrades, but his best friends, also helped him endure the isolation, he said.

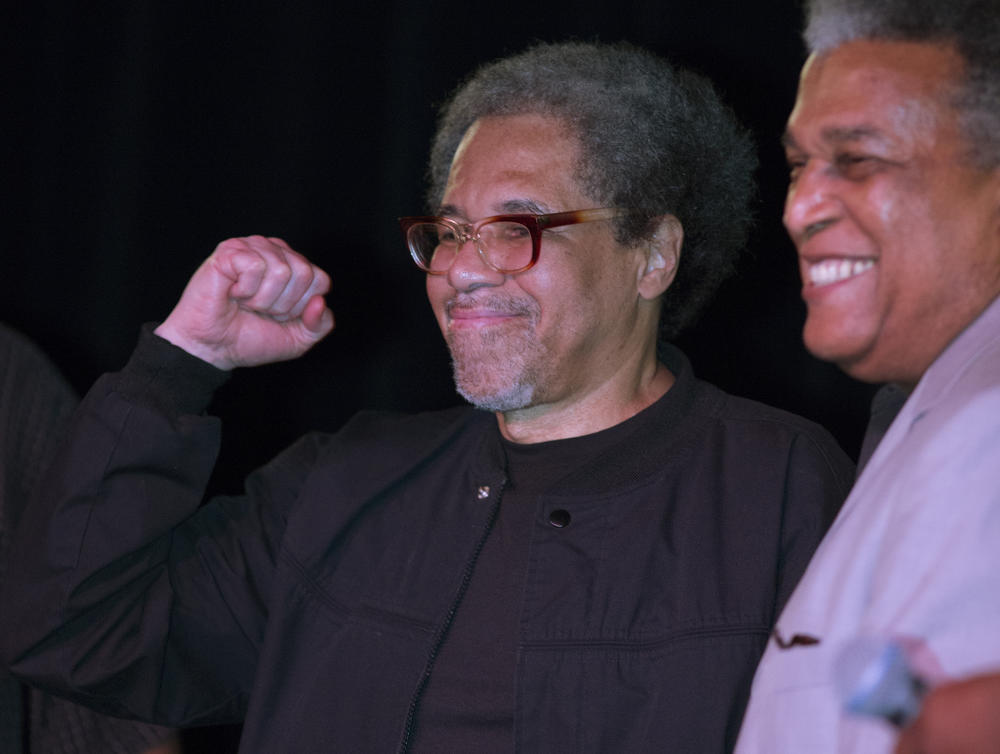

His conviction for Miller's murder was overturned multiple times throughout his time in solitary confinement. Woodfox was set free on his 69th birthday in 2016 after a plea deal to lesser charges.

He spent the next six years educating the U.S. and world on the horrors of the criminal justice system and advocating against solitary confinement.

Woodfox joined King's fight to end solitary confinement in the U.S.

King was released from prison in 2001. Wallace was released in 2013, but he died shortly after from cancer.

Woodfox's 2019 memoir Solitary, which he co-authored with his partner Leslie George, became a Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award finalist.

Throughout the solitary confinement, Woodfox never gave up the hope of being released.

"That's the one thing I didn't give up. When this first started out, we knew that, if we were going to survive, we had to look for strength from the outside, from society, so instead of turning inward and becoming institutionalized, we decided that we would turn outward to society," he said in a 2016 interview on NPR's All Things Considered.

"I would not allow prison staff to define who I was and what I believed in," he added.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.