Section Branding

Header Content

After a career of cracking cold cases, investigator Paul Holes opens up

Primary Content

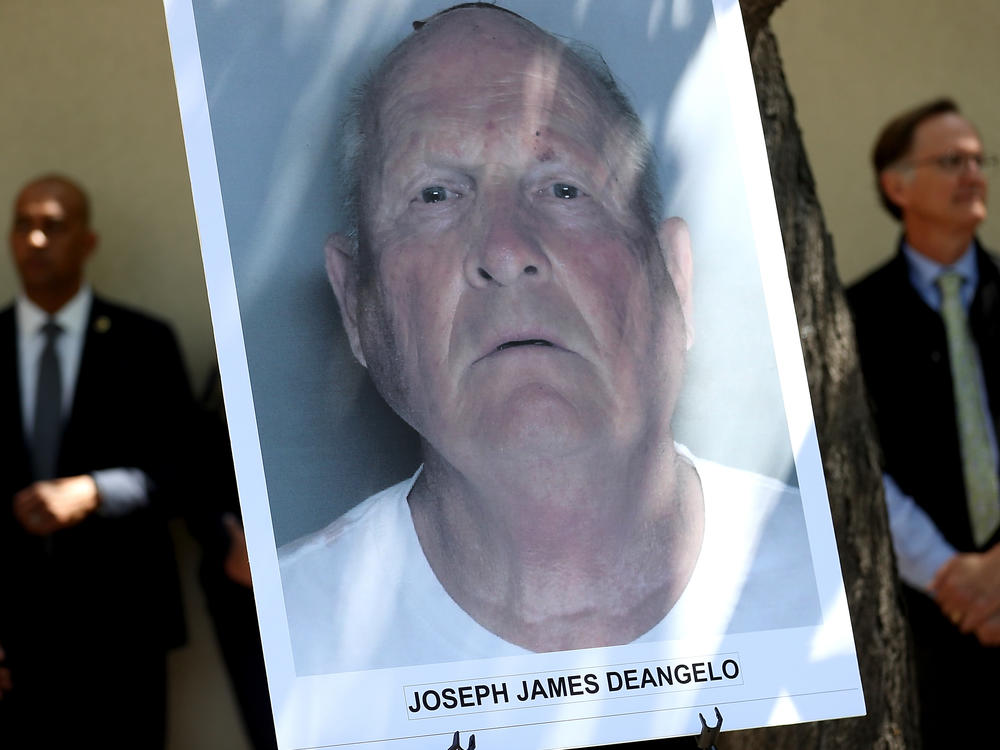

Veteran cold-case investigator Paul Holes spent decades working California crime scenes. He played a critical role in identifying former police officer Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. as the so-called Golden State Killer, a notorious serial predator who was responsible for at least 13 murders and 50 rapes in the 1970s and '80s.

In fact, the day before Holes retired, he drove to the home of DeAngelo, then a prime suspect, and debated knocking on the door to ask him for a DNA sample.

"Generally, over the course of my career, I worked my cases alone. I very much was a lone wolf. And once I decided that Joseph DeAngelo was interesting enough to receive my full attention, I just made an independent decision to drive up there [to his house]," Holes says.

But, sitting in his car in front of DeAngelo's house, Holes began to have second thoughts: He was by himself, without radio contact with dispatch. What if the suspect pulled a gun? What if Holes accidentally blew the case that his colleagues had been building?

"In hindsight, this was foolish from an officer safety standpoint," Hole says. "Fortunately I didn't go up to the door."

Holes didn't confront DeAngelo that day, but law enforcement officers eventually did make an arrest. In 2020, DeAngelo pleaded guilty to more than a dozen murders.

In a new memoir, Unmasked, Holes writes about his decades-long search for the Golden State Killer, as well as his investigative work on other cold cases. He also reflects on the emotional toll of obsessing over gruesome crime scenes and talking with survivors of horrific crimes and relatives of those who have been killed.

"It really wasn't until after I retired and I just had this psychological meltdown," he says. "I went in to see a therapist and I talked about my experiences during my career. And that therapist said, 'Paul, you got to understand, every time you buried that emotional trauma from these cases — which was many cases — those are little nicks that you get. And now you have so many nicks, you're bleeding out emotionally.' I didn't recognize that over the course of my career. But I will tell you, it's very real and a lot of other people are experiencing that."

Interview highlights

On how he came across the case of the East Area Rapist (later known as the Golden State Killer) in the '90s

This is an offender that actually started up in Sacramento in mid 1976 and was attacking all over the East area of Sacramento, Citrus Heights, Rancho Cordova, etc. So that's how this rapist got his moniker. But then, in mid-'78, he moved down to the East Bay into my jurisdiction, and those were the files that I was looking at. And I was hooked because as I read the victim's statements about what this offender was doing to them, what he was saying to them, the fact that he was going in, too, in the middle of the night and attacking couples, a man and a woman, I recognized that the psychology of this offender was very different than the typical serial rapist. This was a much bolder and more brazen offender.

On why it was helpful to visit all the houses where the Golden State Killer's crimes took place

The geographic spread was huge. The moniker "Golden State Killer" is so apt because he really was moving around hundreds of miles between cases. So that was informative. But also looking at the neighborhoods where he's attacking, it helped inform me about his tactics on how he's approaching a particular house, how he's leaving that house, how he's prowling through a neighborhood. Why is he choosing that type of neighborhood?

One of the most informative aspects that I saw as I was visiting these neighborhoods was that he wasn't attacking in lower-income areas at all. He was often attacking in upper-middle to even what I would consider close to upper-class neighborhoods. A lot of the early investigation really focused in on a sort of what I call the "troll under the bridge offender" — this homeless sexual deviant that's driving a beater car. And as I'm looking at these neighborhoods going, "If somebody like that showed up in this type of neighborhood, he would stand out." And so that's when I started to get insight as to who my offender could be: He blends in with the people who live in these types of neighborhoods.

On how victims were traumatized that the rapist was still at large

I had one woman who went to a vacation house. She had a cabin up in the foothills, and the thermostat was set different than what she remembered setting it [at] when they had previously left, and she calls me and it's nighttime and she's saying, "I think he's been here." So she's constantly thinking that this guy is going to come back. I had another woman who, after hearing about a potential suspect in Sacramento and he was still out and about, she moved to Mexico. She wanted to get away because she thought he would come back. These victims, after he left, they continued to be traumatized by the thought that he was still out there. And the East Area Rapist played on that because he would call some of these victims, sometimes years later, to let them know he was still around.

On collaborating with late crime writer Michelle McNamara, who later died from an accidental overdose while in the middle writing I'll Be Gone in the Dark, her book about the case

Michelle, though she had been tasked with writing the book, she really ended up trying to investigate the case. She just became like one of the assigned investigators. Now she's investigating the case and not doing as much writing. It's a huge case. There's a lot of pressure. ... You have 15,000 pages of case file information. Imagine how long it would take to read a novel that's 15,000 pages long, so it's a lot of data to go through. And it's an emotional roller coaster ride. Michelle, just like I, experienced thinking, "Oh, I found a guy. He looks good!" And then ultimately the DNA shows he's not the guy. And that's an emotional crash. And so she's experiencing that. Plus, she has the pressure of writing the book. ...

What she was continuously doing was scanning all these documents. She was putting them up in a file transfer service. I received an email from that file transfer service that there was something from Michelle waiting for me and I received that email after I found out she had died. And I went and downloaded that file. In some ways, she was still helping me.

On how genealogy was used to identify the Golden State Killer

This technique really is what genealogists were using to help adoptees find biological parents. And it's a matter of taking your unknown DNA or Golden State Killer DNA, searching the various genealogy DNA databases that we were permitted to search, getting a list of relatives that share DNA with the Golden State Killer, and now just doing straight genealogy, relying on public records in order to build family trees back, to identify a common ancestor, somebody that the Golden State Killer would be a descendant of. And then building that family tree down into the current time and getting a list of names of people who all have a California connection are the right age, and we just start investigating these individuals to try to determine: Do they circumstantially add up to being somebody we need to get a direct DNA sample from to compare to the DNA that we have from the crime scenes of the Golden State Killer?

On if DeAngelo is what he had imagined

As I investigated the case, I really came to the conclusion that our offender is Sacramento-based, probably still living in the Sacramento area, which DeAngelo was. And I also concluded that I am dealing with a sophisticated and intelligent offender. Turns out the offender, the Golden State Killer, was a former cop. He understood law enforcement tactics. He had been trained as an investigator for burglaries. So he had skill sets that were up and beyond the average person in order to be able to develop tactics and get away with these crimes.

On burying the trauma of working these cases — and ultimately having a breakdown

When I'm working on, let's say, a homicide of a child and I'm looking at this child laying there, but then I see the toys in the room. I see photos of this child enjoying life [and] that ends up weighing on me. And when I would go home in the evenings and I would have similar aged children in my house, I had two kids at this point. I couldn't separate that. That's where the work starts to overlay on the personal life. But, you know, you can't show weakness. I cannot show weakness in the law enforcement setting. I had to be able to stay focused in order to do the job. And I would just bury that type of emotional trauma. ...

So this is where the message with Unmasked is not only talking about the pursuit of the Golden State Killer and these other cases I was involved with, it's really trying to convey that this profession has an impact on the individuals working it, their sacrifices these individuals have made of themselves, of their families. And that turns out really is why this book exists. It's now the fundamental message that I want to get out there.

On true crime as entertainment

I very much am in the true crime genre – but I come out of real crime. And I emphasize to people, like when I'm at the true crime conventions such as CrimeCon, that it is fine to learn about these cases, to learn about these offenders. You don't glorify the offender. But you have to realize that real people were affected — and some of these people are in this room, if we're at a conference. ... A fundamental message that I am trying to continue to press, is that of course, we say it's entertainment, but within the true crime genre, we need to make sure that there is that ethical responsibility of understanding that this is real life. And it's OK to watch these shows. It's OK to listen to the podcast, but continue to understand that people's lives have been affected.

Sam Briger and Seth Kelley produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Natalie Escobar adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2022 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.

Bottom Content