Section Branding

Header Content

Drones patrol off Georgia for hurricane data

Primary Content

Mary Landers, The Current

Two robots are patrolling the sea off Georgia this month. Their mission: collect and transmit real time data to help scientists better predict hurricane activity.

“The idea is to have one robot on the surface measuring the meteorology in the surface oceanographic conditions, while we have another robot underneath it, measuring temperature and salinity,” said Catherine Edwards, associate professor at UGA Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, and in the Department of Marine Sciences at the University of Georgia.

Edwards and her colleagues launched an underwater glider last week from the deck of the R/V Sam Gray about 20 miles off Richmond Hill in the waters of Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary. The bright yellow vehicle looks like a torpedo with wings. It’s nicknamed Franklin after Benjamin Franklin, who was the first to chart the Gulf Stream, a river of warm salty water about 80 miles offshore. Waiting for the glider was a blaze orange Saildrone vehicle — identified not by nickname but number as 1095. Researchers had remotely piloted the solar and wind-powered Saildrone from Jacksonville for the rendezvous.

Saildrone is a California company that designs, manufactures, and operates unmanned sailing vessels. The hurricane project works with the Saildrone vehicles to measure solar irradiance, barometric pressure, air temperature, humidity, wind, waves, water temperature, salinity, chlorophyll, dissolved oxygen and ocean currents.

After running Franklin through its test paces Wednesday, it was time to go, said Karen Dreger, lead glider technician.

“It’ll hang out at the reef a couple of days and then go offshore,” she said.

The Saildrone will go with it. The two robots will spend August patrolling an area that extends from Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary, about 20 miles off Richmond Hill, out to the Gulf Stream.

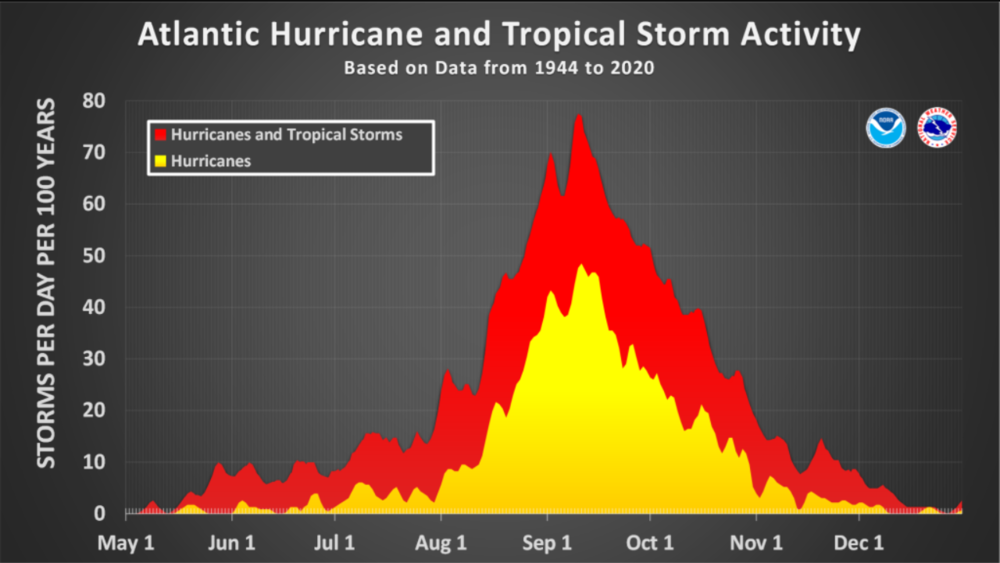

So far, the Atlantic hurricane season has produced three named storms and no hurricanes. But what’s typically the most active portion of the season is yet to come. Hurricanes and tropical storms ramp up in August to a peak in mid-September and then decrease again through October. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is still predicting an above-average season this year with 11-17 named storms before the season ends Dec. 1.

The Saildrone reports back to shore via satellite. The glider surfaces every four to six hours and also “phones home” with its data. Scientists around the world feed the data into hurricane models. As they improve the amount and accuracy of the data input, the models get better at predicting the strength, intensification and path of hurricanes.

The hurricane project includes seven Saildrone vehicles. There are five in the Atlantic and Caribbean, two in the Gulf of Mexico. Edwards estimates there are two or three dozen gliders in these areas, with a dozen of them earmarked for this hurricane project but all of them sharing data.

The Saildrones are paired with gliders when possible to collect data in the same place. “The Saildrone measures the temperature and the humidity, but it also measures how much energy is coming into the ocean from the atmosphere,” Edwards said. “It also measures the parameters we can use to calculate how much heat is coming out of the ocean. Ultimately, that heat coming out of the ocean is available to potentially fuel hurricanes and tropical storms and other other meteorological activity.”

What’s happening below the surface is equally important.

“The glider gives you the integrated heat potential — how much heat is in the ocean, that might be available to exchange with the atmosphere,” Edwards said.

Salinity measurements refine the predictions. Since fresher water is less dense, it floats atop saltier water and acts as insulation.

“The lower salinity layer prevents the heat from mixing into the atmosphere,” Edwards said. “That’s important in areas like the Gulf of Mexico and actually in the Caribbean, where there’s influence of Amazon water even far away from the mouth of the Amazon.”

The Saildrone vehicle is equipped with specially designed hurricane wings. The shorter, more rugged wing is designed to withstand hurricane strength winds and waves.

Edwards is a physical oceanographer, meaning she studies of the physical processes in the ocean and the interaction of the ocean and the atmosphere. She was a physics major as an undergrad at the University of North Carolina, but jokes she’s not necessarily a model for girls in STEM: “I did it to impress a boy,” she said. When she’s not working with underwater robots you can find her jumping out of airplanes. She’s completed more than 300 skydiving jumps.

But she also gets thrills from science. Like the time last year when she and her colleagues guided a Saildrone vehicle right into Hurricane Sam.

“We were all watching the data,” she said. “We saw the light measured by the Saildrone go up in the middle of the storm. And that’s how we knew we were in the eye of the hurricane. It was the closest thing to a NASA control room celebration that I’ve ever had.”

Edwards leads a group of glider observers located from Florida to North Carolina that she calls jokingly calls a “hippie glider commune.” Other institutions involved include University of North Carolina, University of South Florida, and Georgia Tech.

The drones have already improved forecasts and Edwards and her colleagues aren’t finished yet.

“We’re getting better faster,” she said. “The forecasts are better and there’s more integration of science into these forecasts. I want to see people have faith in science.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current, providing in-depth journalism for Coastal Georgia.