Caption

Turning vehicles trap a man in the crosswalk at Spring Street and Riverside Drive as he tries to walk across the busy street.

Credit: Liz Fabian/Macon Newsroom

Turning vehicles trap a man in the crosswalk at Spring Street and Riverside Drive as he tries to walk across the busy street.

Each time a person dies on Macon highways, cries for road improvements resound, but the issues are complicated. Solutions are never immediate, often elusive and expensive.

The quest for pedestrian safety measures on deadly stretches of Gray Highway reached new levels of exasperation recently, prompting high-level talks this month between Macon-Bibb County and Georgia Department of Transportation representatives.

For years, Macon has been one of the deadliest cities in Georgia for pedestrian crashes, yet local leaders continually express frustration that their concerns about state highway safety are not being heard or acted on by the state.

The Center for Collaborative Journalism has been actively studying and delving into pedestrian safety concerns for more than seven years. Most recently, journalists working with The Macon Newsroom have been trying to identify where the disconnect comes between passionate pleas, public policy and where the pavement meets the road.

The majority of Macon’s pedestrian fatalities occur on state highways where speed limits are higher – Gray Highway, Pio Nono, Eisenhower Parkway and Ga. 247.

While some issues are being addressed, there is much discussion at various transportation and pedestrian safety committee meetings that Gray Highway is a glaring omission that should be more of a priority.

At the last meeting of the Citizens Advisory Committee of the Macon Area Transportation Study, or MATS, two citizen road safety advocates refused to sign off on pedestrian improvements planned for Eisenhower Parkway in protest of the lack of attention afforded Gray Highway.

“I’m perplexed that GDOT would choose a project like that instead of Gray Highway where most of our residents are being killed crossing the street,” said Lee Martin, a two decadeslong member of the Citizens Advisory Committee, or CAC, who voted against GDOT’s favored projects. “If we vote no, maybe they will listen to the CAC who are doing their best to represent citizens who are crying for safety improvements.”

To coordinate, maximize and plan for federal and state funding, MATS, a regional planning organization, regularly assembles stakeholders from Bibb, Jones and Monroe counties to plod through projections for decades ahead.

MATS’ oversight of local transportation projects includes the Citizens Advisory Committee, Technology Committee and Policy Committee that are all updated on the progress of pending construction and work underway. Projects require a series of approvals at several stages of development and design.

In the lengthy GDOT approval process to identify and fund projects for future improvements, the CAC has just one vote on the Policy Committee which is made up of about a dozen members, so it could not halt the Eisenhower project to place the priority on Gray Highway.

On Eisenhower or U.S. 80, from Canterbury Road/Key Street to Interstate 75, “road diet” plans are proceeding to narrow lanes, add rumble strips and sidewalks on the north side of the highway.

“I’m not opposed to it, it’s just not as dense as Gray Highway,” Martin said during the last CAC meeting. “I don’t like to see pedestrians killed who have every right to cross the street wherever they want to.”

Martin, who said he has served on the CAC for more than 20 years, continually voices frustrations that Gray Highway enhancements appear to have been overlooked by GDOT in favoring other projects.

“I’ve asked for years. How do we get projects into this pipeline that we have to vote on over and over, and I haven’t gotten an answer,” Martin said. “I think they’re building killing roads and killing fields and I think it needs to change.”

Tapping into the right connections to get answers in a bureaucratic behemoth like GDOT is not easy, especially with the turnover of staff in recent years. GDOT spokeswoman Natalie Dale said employee staffing is not a unique challenge for the department.

“Like all industries, GDOT has experienced substantial turnover in all levels in the past few years,” Dale said. “But I would not say there is a link between staff turnover and Gray Highway being forgotten.”

Since road construction is costly and financial resources are limited, GDOT has several ways to fund improvements, including the department’s safety department and budget for each district. Local Maintenance Improvement Grants, or LMIGs, are also doled out from the state to local government entities. Projects can also be funded directly by private entities and local governments.

Finding funding for major projects is a competitive process.

Georgia has seven transportation districts with Bibb being one of 31 counties in District 3, headquartered in Thomaston.

“As a district, we communicate with local jurisdictions all the time,” said Daniel Trevorrow, District 3 traffic engineer, who is responsible for the operations of the state highway network across the West Central District. “We’re always on the lookout for things that need improving, whether it be intersections, corridors, signal upgrades.”

At the district level, Trevorrow conducts engineering and speed studies independently or at the request of local jurisdictions.

Every year, each GDOT district allots and performs two road safety audits, or RSAs, that study road conditions and highlight areas of improvement needed on highway corridors. An RSA can be the first step in enhancing road safety, but those studies are just one of many factors considered when putting projects in the pipeline.

“One of the most important data points that we use is crash data,” said GDOT’s Christina Barry, an assistant state traffic engineer. “So, if we see… pedestrian crashes in a certain location, we’re going to target that location no matter what… even if it’s designed perfectly, exactly to standards, if we’re having fatalities there, there’s a problem and we need to fix it.”

Barry is an expert on GDOT’s Complete Streets program passed in 2012 that standardizes accommodations for pedestrians, cyclists and mass transit in all transportation projects with GDOT oversight. As of 2013, a project must comply with Georgia’s Complete Streets policy to proceed to the final design or right-of-way approvals.

New pedestrian crossings lead to a drainage ditch on Bass Road at the Interstate 75 off-ramp.

That policy is responsible for automatic enhancements such as the “crosswalks to nowhere” that lead to drainage ditches at refurbished traffic signals at the I-75 entrance and exit ramps at Bass Road.

The GDOT chief engineer must approve any variance to the Complete Streets policy by weighing the cost-benefit of those accommodations.

The state also is trying to work toward an 80 percent reduction in pedestrian and bicycle deaths and serious injuries by 2023 under the Federal Highway Administration and National Highway Administration Pedestrian Safety Action Plan.

Last year, Macon-Bibb approved its own Complete Streets Policy that mandates road improvements be tailored for all forms of transportation, not just vehicles. In 2016, the county also embraced a Vision Zero philosophy aiming to eliminate all traffic fatalities and serious injuries by 2040.

The same year Vision Zero was endorsed, a road safety audit of Gray Highway led by Macon-Bibb County and Planning & Zoning noted hundreds of housing units along the state highway and “no pedestrian facilities.”

In 2016, GDOT also worked with the county on an RSA of Eisenhower Parkway, which has already resulted in several improvements including a hybrid beacon pedestrian crossing system at C Street, which is also known as HAWK, which stands for High-intensity Activated crossWalK. GDOT also reconfigured intersections and built crosswalk enhancements at Oglesby Place, Central Georgia Tech Drive and Bloomfield Road as a result of that RSA.

GDOT initiated that road study after a review of Georgia Electronic Accident Reporting System data from that highway.

Shauntraveious Napier was 12 when he died after being hit by a pickup while trying to cross Eisenhower from Murphey Homes at C Street.

Pedestrians can now push a button to launch flashing lights on the HAWK system that lead to a red light for vehicles to stop and allow people to cross. Despite this safety device, one of Macon’s latest pedestrian fatalities occurred just up the street from that crossing.

On July 1, 61-year-old Lee Tukes was hit and killed while walking across the westbound lanes of Eisenhower. First responders were called out earlier that night after getting a report that Tukes was lying on Second Street, but he got up and left the scene, according to the Macon-Bibb County Fire Department.

His death will be included in data GDOT regularly reviews, but in this case, a potentially life-saving road feature was already in place.

Although Macon-Bibb adopted the Complete Streets philosophy last year, the first meeting of the Complete Streets Compliance Committee wasn’t held until July 14.

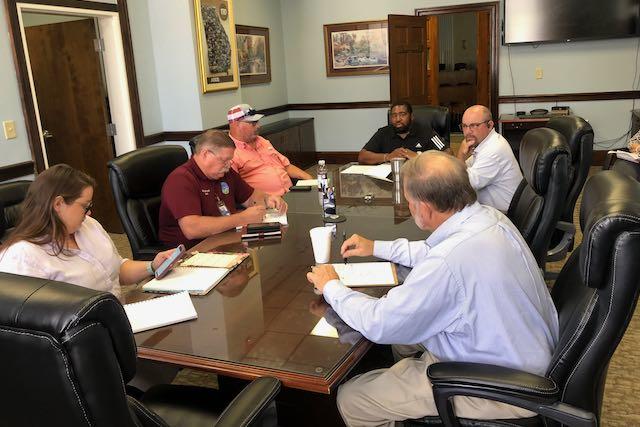

The Complete Streets Compliance Committee met for the first time July 14 where pedestrian dangers dominated debate.

In addition to the county’s Pedestrian Safety Review Board, which formed in 2015 to study fatalities and find solutions, the Compliance Committee assembles engineers, public works, local planners, facilities management and a representative of the Citizens Advisory Committee to ensure the policy is followed.

At that meeting, John Ricketson of Monroe County, who chairs the CAC, vented his continued dismay that Gray Highway has yet to be added to GDOT’s project list. As often is the case during these local meetings, a debate ensued about that deadly highway and GDOT.

“If they get something in their mind they want to do… it just gets done,” Ricketson told the committee. “We’ve been pushing… the most dangerous street in Macon is Gray Highway and there’s an easy solution for that in calming the traffic and giving a sanctuary (median) and eliminating the left turn. … It’s like pulling teeth.”

Martin interjected: “I would love to see it as a landscaped median rather than just a raised concrete median,” he said. “It’s a huge northside entrance into Macon-Bibb. Why do we want it ugly? It’s already as ugly as it can be.”

“I guess what we have to do is try to get GDOT to look at Gray Highway,” Macon-Bibb traffic engineer Nigel Floyd said. “We need an advocate to push GDOT to look at Gray Highway, take a comprehensive look at Gray Highway.”

“One of our biggest issues is money,” said Macon-Bibb Facilities Management Director Robert Ryals.

If Macon-Bibb had unlimited resources to fund the Gray Highway work on its own, it’s likely GDOT would give its blessing to the project.

Many of the state’s major transportation projects rely on federal funds that must be allocated throughout GDOT’s seven districts.

“We ultimately have to prioritize funding based on feasibility to deliver, safety benefits and mobility,” said GDOT spokesperson Natalie Dale. “Gray Highway is just one of many state routes within Macon-Bibb and there are other corridors where we have made many improvements. That shouldn’t indicate that Gray Highway somehow was set on a shelf and forgotten about.”

Kelli Roberts, GDOT’s state safety engineering supervisor, said road safety audits have changed dramatically in the five years since locals studied Gray Highway.

“The level of analysis that we do in terms of RSAs has definitely changed,” Roberts said. “We’ve still made the effort to go through all of our… what we would refer to as historic RSAs and make sure they’re addressed.”

Once a corridor is studied, recommendations and improvement sketches come next but don’t guarantee work will be done.

“There’s a ton of things that come up on RSAs. So, in terms of what actually happens next step is very dependent on the scope of the actual recommendations,” Roberts said. “We are a benefit-cost driven program.”

In other words, if GDOT determines the benefit of a safety project justifies the cost, the project moves to the next step in GDOT’s safety program.

“If it becomes a full, safety-funded project, it’ll go through what we call our planned development processes to become an actual project with allocated funds and eventually constructed and delivered,” Roberts said.

All of that does not happen overnight. Planned improvements may happen years later.

“A roadway project, depending on what it is, can take a lot longer than people anticipate it’s going to take,” Barry said. “Because we have to go through conceptual design and then we have to go through full design. You’ve got a right of way process… that can take time.”

Barry suggests local leaders continue to bring projects to the District 3 office for consideration and set clear priorities.

Macon-Bibb County Mayor Lester Miller not only plans to sit down with GDOT, but wants to hire a liaison to bridge the gap between state and local transportation stakeholders.

In the Vision Zero Action Plan adopted in 2020, hiring a local emissary to represent Macon-Bibb at the state level was designated as a short-term goal.

“I’ve also met with a couple of consultants myself for a proposal where they can step in and be that intermediary person with GDOT to make sure we’re addressing things properly,” Miller said during last month’s Ask Mayor Miller taping. “The mayor’s office is going to get a lot more involved in pedestrian safety than we have before… I think they need a little guidance and support.”

Miller earmarked $500,000 for pedestrian safety in his FY’23 budget. The Pedestrian Safety Review Board has decided to use that as matching funds to maximize the dollars by joining state and federal projects.

Typically, federal and/or state funding requires a 20 percent match from the local government.

By investing that $500,000 in a local match, Macon-Bibb could reap the benefits of a $2.5 million project.

Months ago, the county already committed $730,000 for its share of the Eisenhower Parkway project recently approved by the MATS committees.

Through the upcoming summit, Mayor Miller wants to learn how to better communicate the county’s desire for work on Gray Highway and other locations needing safety enhancements.

Although GDOT is responsible for construction and maintenance of state highways, local governments and private entities can self-fund projects.

Kroger and the owners of the Wesleyan Station shopping center privately funded safety studies and construction of a GDOT approved new entrance and signal light in the 4600 block of Forsyth Road.

Recently, a new signal light opened at the southside entrance to the Wesleyan Station shopping center in the 4600 block of Forsyth Road – a trouble spot that has been discussed at the Citizens Advisory Committee.

The owners of the shopping center and Kroger initially wanted to build a new main entrance off Tucker Road, but it was too close to the traffic signal at the corner, according to P&Z meeting notes. In 2019, the property owners instead proposed putting a traffic signal near the Starbuck’s to ease traffic flow where it would typically back up around the drive-thru.

The private entities funded and provided a study for GDOT, which approved the signal permit but required the north side entrance be converted to right-in, right-out only to avoid left turn conflicts. Barriers along the lane now prevent the left turn, but days after the signal was turned on, The Macon Newsroom witnessed a vehicle turning right out of the other entrance, driving past the barrier, pausing in the middle turn lane and doing an illegal U-turn to head north on Forsyth Road.

GDOT signed off on that project, which includes a southbound right deceleration lane near the light, without having to invest a ton of money from its own budget.

“This is a great example of working with GDOT to move on an issue with the study and work being funded outside of GDOT,” said spokeswoman Dale.

The District 3 engineer said GDOT often works with private entities who need entrances to subdivisions, a new business or facility. Local governments, like Macon-Bibb County, could fund pedestrian safety enhancements themselves on state highways, if they had the money.

“If a jurisdiction like Macon-Bibb wants to add sidewalks and they approached us and talked to us about it and we concurred with it, and they were able to fund it entirely, then, yes, there’s ways they can do that,” Trevorrow said.

GDOT also has grants available from its Highway Safety Improvement Program that purchases equipment that local governments can install.

“That allows any locals to submit a request to our office for any safety equipment… that has a documented safety benefit,” Roberts said. “In that program we do purchase the equipment and then the locals would just have to install it with their local maintenance funds. So that’s another resource that we have out there for our Complete Streets that has a little bit more of a faster timeline.”

In the upcoming meeting, Miller intends to listen to GDOT’s recommendations for what can be done with Gray Highway and other safety challenges.

“We’ll have a presentation from GDOT on things we can do and things that have worked in other areas,” Miller said. “I look for some great things.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with the Macon Newsroom.