Caption

Average Monthly Homicides In Georgia Prisons vs. Average Monthly Temperatures 2015-2021

Credit: Grant Blankenship/GPB

|Updated: March 3, 2023 1:37 PM

There was at least some hope of relief from the heat on the cell block. It only took a minute for that to melt away.

In a smartphone video shared with GPB by a Georgia prison rights activist, a group of mostly shirtless men are bent over a big black cart. As the camera pulls back, you see it’s an ice cooler parked on a prison dormitory wing.

“The ice just came in here,” the voice holding the phone says as the men scoop the contents into oversize cups.

It’s clear he has a stopwatch on the proceedings, too. Thirty seconds into the video, and the pile of what one man can be heard calling “treasure” is already dwindling.

“It’s been one minute. How much ice left?” the documenter asks.

The ice was gone.

The Georgia Department of Corrections said doling out ice is one of the stopgap measures they use when prison heat becomes intolerable. Dana Smallwood Linton said she knows this from her son’s experience in his prison.

“It's 90 degrees inside," she said. "How long do you think that ice is lasting?”

To keep our cool in this record hot summer, most of us are probably choosing to spend more time in air-conditioned spaces. For many people in Georgia prisons, that simply is not an option.

Meanwhile, the federal Department of Justice is still investigating Georgia prisons, trying to get to the root of persistent violence there.

They might take a look at the heat.

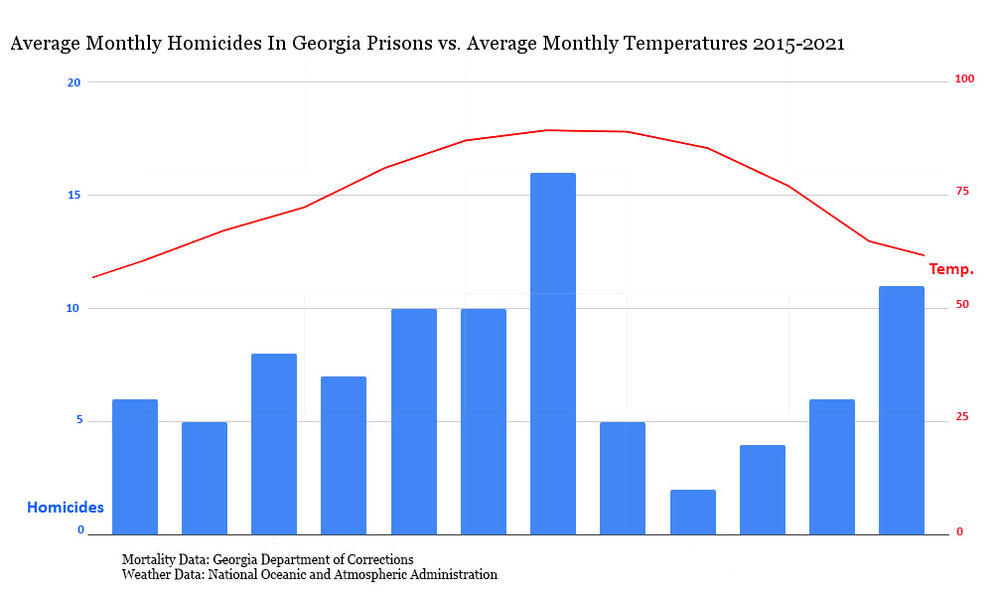

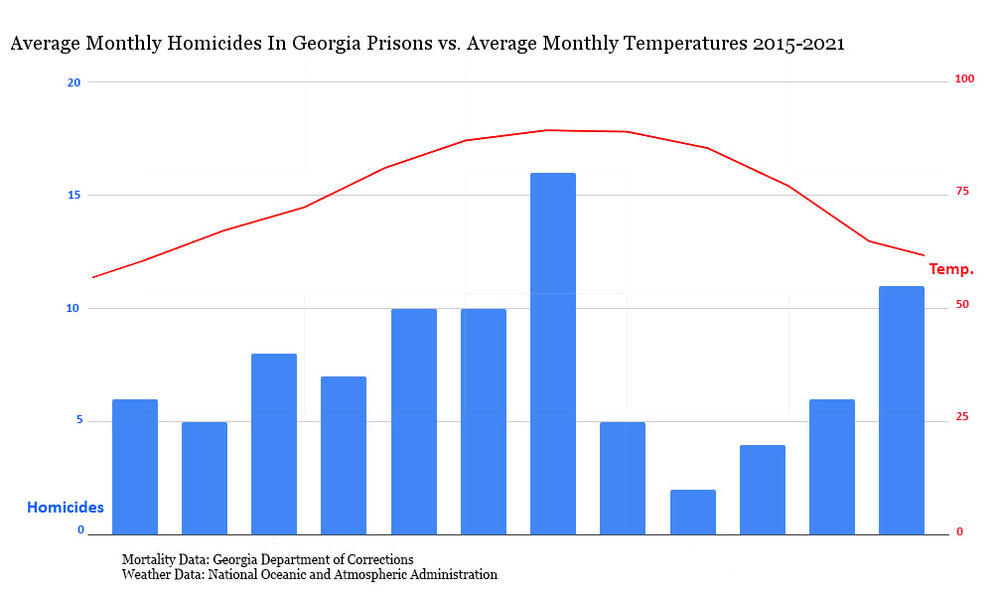

Average Monthly Homicides In Georgia Prisons vs. Average Monthly Temperatures 2015-2021

Only a quarter of Georgia’s prisons are fully air conditioned, making it one of a dozen of states across the South and Southwest with less-than-fully climate-controlled prison systems.

Most Georgia prisons are only partially cooled, which sometimes means cooling in a single dormitory. Linton’s son is at Phillips State Prison outside of Buford, one of two in the Georgia system with no air-conditioning at all.

“They’re in basically a cement pizza oven, is what I literally think of it,” Linton said.

And while Linton said that’s tough enough for her 22-year-old son, it’s misery for others.

“His roommate is an 80-year-old man,” she said. “He very rarely leaves his room because it's so exhausting for him to even walk from his room to the shower.”

The direct threat to physical health from heat is well documented. Heat exacerbates all kinds of pre-existing health conditions. Plus, many incarcerated people take psychiatric medications which very often have a side effect of lowering heat tolerance, too, making inescapable heat that much more likely to lead to hospitalization.

But prison heat presents another danger, too.

“Two weeks ago, they had a death, you know, literally a man was found stabbed to death in his cell,” Linton said.

His name was Sidney Neally.

No one had yet died in Phillips State Prison this year until three deaths in July — typically the hottest month of the year in Georgia. Two of those three July deaths, Neally’s and Jamal Johnson’s, were ruled homicides.

In mortality data kept by the Georgia Department of Corrections, that pattern of homicides peaking on the hottest days repeats itself across the Georgia prison system at least as far back as 2015.

Anita Mukherjee is an Assistant Professor in the business school at the University of Wisconsin. She said that broad Georgia pattern mirrors what she found in a Mississippi study.

“So the question that we started out with is what is the effect of, let's say, a hot day versus a moderate temperature day on acts of violence and prison?” Mukherjee said.

That may sound like a simple question on its face, but Mukherjee and her co-researcher Nicholas Sanders of Cornell University used some sophisticated math to look at eight years of data about extreme acts of violence in the Mississippi Department of Corrections.

“Extreme” was defined as violence possibly leading to a homicide. Their math took into account regional differences in temperature, precipitation and some 50 other variables in order to burrow down to this relationship between heat and violence in their working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

“So the effects that we find, in what generates a response in violence, is days averaging 80 degrees or more,” Mukherjee said.

That’s on 80 degrees Fahrenheit on average. In reality, those are days with highs in the 90s or even 100s — only cooling into the 70s at night.

“Inside the prison it could easily have been 100 degrees or more,” Mukherjee said. “So we think these are quite hot days.”

Depending on whether you are looking at northern or southern Georgia, the state has seen between 30 and 60 of these days in 2022 alone. Mukherjee and Sanders said any single one of those days is likely to see a 20% higher probability of extreme, potentially homicidal violence in a prison setting.

That worked out to around 44 heat-fueled incidents in the Mississippi data. In Georgia, where the prison population is roughly double that of Mississippi, a rough estimate would be 80 extra acts of heat-fueled violence every year.

But climate change means the number of extremely hot days in Georgia is increasing. Exponentially.

South Georgia, the region where most of the state’s prisons are clustered, averages about 100 of these blistering days a year. Compare that to 80 days on average 30 years ago.

So that’s a possible 80 heat-fueled acts of violence and growing. If the Georgia prison system were an American city, it would land in the top five for per capita homicides.

An average of 12 people die yearly in Georgia prisons with no one to bury them. They rest at Georgia State Prison Cemetery near Reidsville. The most recent burial came in July of 2022.

Federal courts have said even just the threat of harm from heat is a civil rights violation.

“And so then pretty soon it violates the Eighth Amendment, you could say,” Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Burling Cain said. That’s the U.S. Constitution amendment that protects against “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Mississippi prisons have been under scrutiny from the federal Department of Justice for potential violations of the Eighth Amendment for years.

“They've already said it about it being hot, hot, hot,” Cain said of the DOJ. “We know it's hot.”

So Cain is currently air-conditioning Mississippi’s infamous Parchman Prison. It’s a first in the prison farm’s 121-year history. He said he would like to air condition the entire Mississippi prison system.

“So it reduces violence, actually,” Cain said. “And it makes better conditions of confinement.”

Cain also said cooler prisons make it easier to keep correctional officers on the job. Understaffing is a major sticking point and a struggle for Mississippi just as it is for Georgia corrections and in other Southern states.

What’s more, Cain said, proactively addressing something like hot prisons helps him keep a step ahead of the Department of Justice.

“If you know what they’re going to complain about, or you know where you may not be in compliance, then it's kind of foolish not to fix it,” he said. “We don't want to get the consent decree like Alabama.”

It’s still early days in the Department of Justice investigation of Georgia prisons, so it remains to be seen if the issue of heat surfaces in DOJ findings.

The Georgia Department of Corrections declined to comment for this story.