Section Branding

Header Content

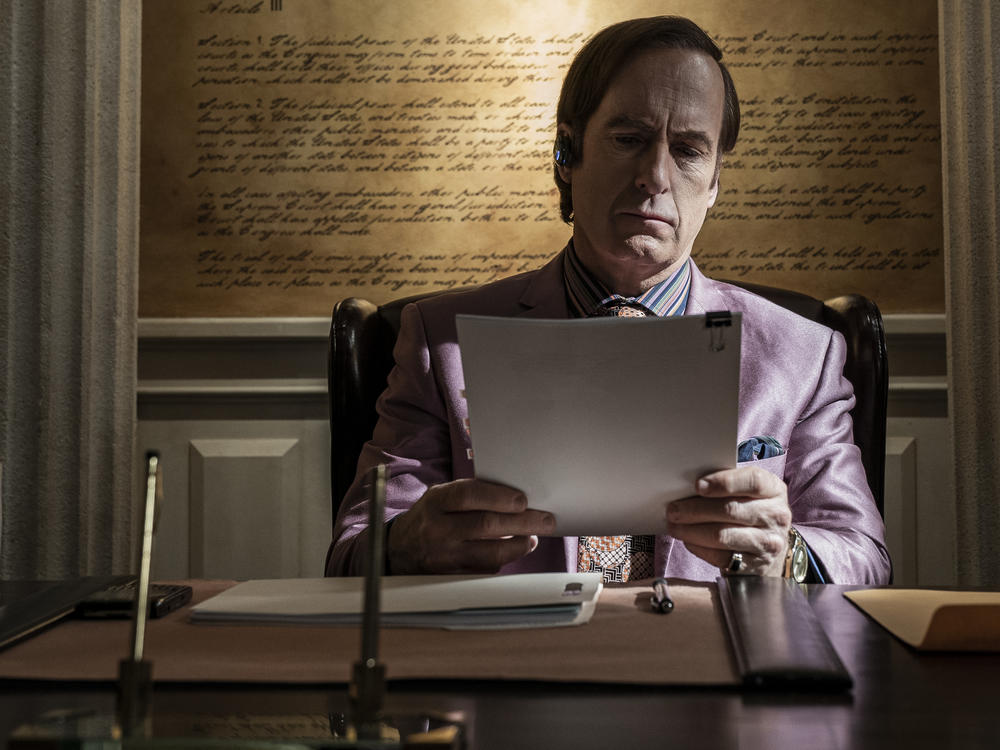

'Better Call Saul' finale soars as a meditation on consequences and regret

Primary Content

(Fair warning: This story has LOTS of spoilers about the Better Call Saul finale episode, "Saul Gone.")

In the end, the question that loomed largest in the poignant, masterful series finale of AMC's magnificent drama Better Call Saul wasn't whether main character Saul Goodman – a.k.a., Gene Takavic, a.k.a. Jimmy McGill – would go to jail.

Arrest and incarceration seemed inevitable, given the events of last week's episode, where Saul – who had been hiding from the law under the name Gene Takavic, working a soul-deadening job as manager of a Cinnabon restaurant in an Omaha mall – was exposed to police. He'd been found out by the mother of an accomplice to a new scam he'd put together, unable to resist the lure of getting back in the criminal game.

(Shout out to comedy legend Carol Burnett, who knocked it out of the park playing feisty mom Marion. And props to the show's producers, who had the guts to cast her for their final few episodes, in a role that began as a glorified cameo and grew into one of the most pivotal exchanges of the series.)

Instead, the question that hung over the show's final episode was a simple one: Would Saul ever grow a conscience? Would he ever let himself feel real regret?

An ambitious spin-off idea

Better Call Saul began in February 2015 as an ambitious project: a follow-up to one of the most acclaimed dramas in modern TV history and an origin story for Saul, one of Breaking Bad's most outrageous characters.

The spin-off kicked off with a scene showing Saul after the events in the Breaking Bad finale. He's living under the radar as Gene Takavic, working a menial job, depicted in footage shot in a drab, black-and-white format that seemed both elegantly cinematic and drained of all life or enthusiasm. Right away, it established the elaborate two-step that would define the series, toggling between Gene's drab life in the present and his evolution into Saul, which intensified in the last few episodes.

Those images answered a question that had been nagging Breaking Bad fans since they watched high-school-teacher-turned-drug-kingpin Walter White meet his maker in that show's finale two years earlier. Whatever happened to Walter's fast-talking attorney, an amped-up counselor for drug cartels who had TV ads like a personal injury lawyer and patter like a used-car salesman?

After that quick introduction to Gene, the first episode of Better Call Saul jumped back in time six years, transitioning to color and introducing viewers to aspiring attorney Jimmy McGill (Saul's given name). Once known as "Slippin' Jimmy," for his habit of falling in front of businesses to scam injury settlements, he was struggling to make ends meet and caring for his brother Chuck, once a brilliant lawyer, who had to step down from his law firm.

In 2015, I talked with star Bob Odenkirk about playing Saul/Jimmy/Gene, and series co-creators Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould. Odenkirk said the crew on Breaking Bad had always joked about Saul getting his own spin-off series, while Gilligan marveled at how "heroic" the character could be, referring to Saul's efforts to take care of his brother.

But Gould, who would later write and direct Better Call Saul's finale episode "Saul Gone," said at a press conference back then that the show would turn on a niggling question. "Why be good?"

"Usually, in fiction, behaving ethically always ends up having good results," he said. "And we all know, in life, sometimes being ethical lands you in the s------, so to speak."

Creating the best drama on TV

Better Call Saul would spend the next six seasons exploring that answer, producing some of the best drama on television. We saw Saul confront his brother at a hearing before the bar association, exposing his sibling's unbalanced belief that he was overly sensitive to electromagnetic fields. Chuck, played with agonized grace by Michael McKean, eventually committed suicide.

We saw Saul marry Kim Wexler – played masterfully by the Emmy-nominated Rhea Seehorn – a much better lawyer who is attracted to the rule-breaking scams her husband dreams up until, seeing the awful collateral damage they can bring, she decides to leave him and the law behind.

It's a testament to the show's quality that these new characters became just as compelling as figures from Breaking Bad who rejoined the party, including Jonathan Banks' magnificently tortured cop-turned-cartel enforcer Mike Ehrmantraut, and Giancarlo Esposito's controlling drug kingpin/fast food entrepreneur, Gus Fring.

Even Odenkirk's real-life heart attack — which came as he was filming one of the show's final episodes and nearly ended his life — didn't stop the completion of the story.

The series showcased the increasing dissonance between the guy Saul thinks he is trying to be – a sharp, savvy lawyer who finds the simplest solution to any problem – and the toxic consequences he creates for others. The finale season wove all these threads together in a tremendous climax, when a lawyer who is being scammed by Kim and Saul is unexpectedly killed by Gus' biggest rival — a murder which would not have happened if the lawyer, Patrick Fabian's officious Howard Hamlin, hadn't been wrapped up in the couple's con artistry.

Producers took massive creative swings that turned episodes into high-wire acts. Four episodes before the finale – not long after the lawyer's shocking death — they plunged the story back into Gene's world, shifting to black-and-white images in a way that almost felt like a different series had started.

The finale episode stuck to that black-and-white format, showing a captured Saul negotiating a deal with prosecutors for a light sentence, before realizing Kim had already confessed to their role in the lawyer's death.

Saul then lies to get Kim into the courtroom for the finalization of his plea deal, where he admits to everything he did to enable Walter White's drug empire and his participation in Hamlin's death. This is the moment Saul becomes Jimmy again; a man taking responsibility to regain the respect of the ex-wife he still loves. (Among a very long list of artful cameo appearances in Better Call Saul, the return here of Betsy Brandt as Marie Schrader, wife of a DEA agent murdered in Breaking Bad's finale season, ranks as one of the coolest.)

In the final scene, as Saul shares a cigarette with Kim during a prison visit — he was sentenced to 86 years, after all — the question Gould asked way back in 2015 seems answered.

Why be good? To have a clean conscience.

Common ground between "Breaking Bad" and "Saul"

Different as Better Call Saul's story ultimately was, its finale also revealed a fundamental similarity with Breaking Bad. Both shows are about men facing something terrible at the core of their being, admitting the horrific damage they have caused and, finally, accepting the consequences of their behavior.

In stories about antiheroes, there is always the question of what separates them from villains. Why do we root for Tony Soprano and not his Uncle Junior on The Sopranos? Or champion Ozark's fast-talking financial planner Marty Byrde over cartel leader Camino Del Rio? Often, the difference is values and a conscience; antiheroes have them, and villains don't.

On The Sopranos, creator David Chase seemed to relish slowly stripping away all the stuff which had allowed fans to see Tony as the kind of charismatic outlaw we love in pop culture – which forced the audience to admit they had been rooting for a psychopath all along.

But Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul tell a different tale. In these shows, the antiheroes are forced to face the toxic truth about themselves, ultimately taking responsibility for the pain they have created as a final admission to those who love them and realized the truth about them long before they did.

My thinking on this is influenced by a conversation I had with Vince Gilligan many years ago. We were hanging out at a press reception for Breaking Bad, which was still several seasons from its end. I noted how much I was enjoying watching this show about the slow curdling of a man's soul, as a high school chemistry teacher dying of cancer morphed into a ruthless, boundlessly wealthy meth manufacturer.

Gilligan, who has a well-deserved reputation as one of the nicest showrunners in TV, gently corrected me. What if, he suggested, you saw the story as slowly revealing something about Walter White that was already there? Perhaps what's really happening is that all the things in society which kept him in check are slowly falling away, and he's flowering into the controlling, ruthless narcissist he always was at his core?

This is why Saul's questions about regret, featured in two crucial scenes from the finale, mean so much. In flashbacks, he asks two of the franchise's other antiheroes – Jonathan Banks' Mike Ehrmantraut and Bryan Cranston's acerbic Walter White, in another inspired cameo – what they would change about their lives if they had a time machine.

White acidly and correctly points out that Saul is really asking about regret. In other words: What would you undo in your life, if you could?

Mike wanted to undo the moment he took his first bribe as a cop. Walt wanted to take back his decision to walk away from a successful company he created, leading to a bruised ego which fueled all his subsequent dysfunction.

Saul's answers were always about making more money, executing a better scam, finding a better way to come out on top. And comparing his answers to his compatriots, Saul (and viewers) could see something important was missing.

The series began with Jimmy McGill desperate to prove that everyone in his life who saw him as a loser had it all wrong. And it ended with a bravura finale showing Saul Goodman realizing those people were more right about him than he wanted to admit.

That is the stuff of legendary television.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Correction

In a previous version of the story, we said that Patrick Fabian played Harry Hamlin. In fact, the character's first name is Howard.

Bottom Content