Section Branding

Header Content

For Kashmiris, resolution to decades of conflict remains a distant dream

Primary Content

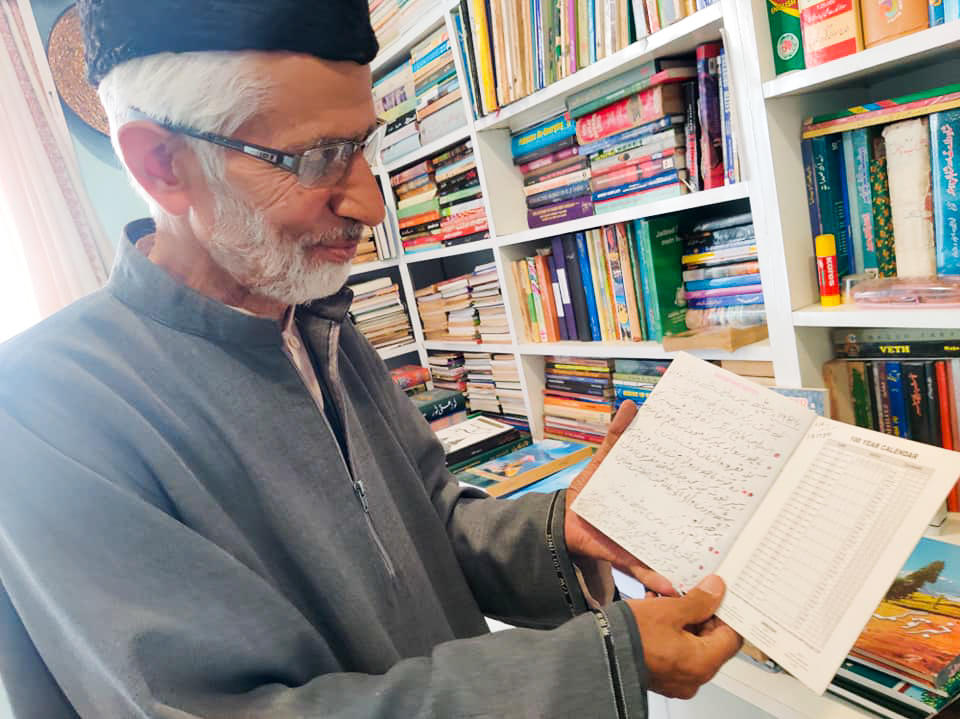

SRINAGAR, India — Kashmiri poet Zareef Ahmad, 80, has unmatchable energy. He talks animatedly and feels passionately about his past. His study is filled floor to ceiling with books in Urdu, English and Farsi — some of which he has authored.

Ahmad won India's highest award for literature. But one of his most prized books is a small notebook filled with handwritten notes in Urdu.

Carefully cataloged are exact dates and locations of the hundreds of chinar trees he has planted in various parts of Kashmir for over 30 years. "I have planted them in police stations, government offices and universities, where they can use its shade to cool off tensions," he says.

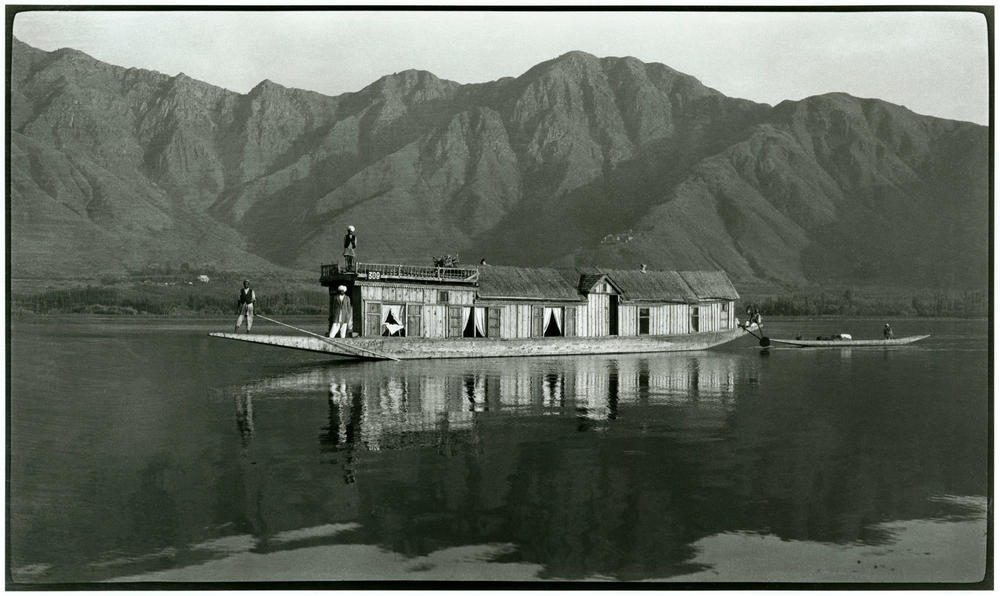

The Himalayan region he calls home — hailed for its picturesque alpine beauty — has been roiled by conflict for decades, with both India and Pakistan staking claim to it. When Indians mark 75 years of independence this month, Ahmad and others in Kashmir may feel there's not much to celebrate.

A painful history

Pakistan was created as a homeland for the Subcontinent's Muslims when it and India emerged independent from British-ruled India in August 1947. But Kashmir's Hindu maharaja decided his Muslim-majority princely state would join India after armed tribesman from Pakistan invaded the region in October 1947.

A United Nations-brokered cease-fire ended those hostilities in 1949. But over the decades, the two nuclear-armed neighbors have fought other wars over Kashmir and there have been more crises. Today, both India and Pakistan administer some parts of the territory. In India, it's called Jammu and Kashmir, and in Pakistan, it's known as Azad (Free) Kashmir.

In India, Kashmir has become emblematic of the country's recent authoritarian slide under a Hindu nationalist-led government. In August 2019, India revoked Jammu and Kashmir's constitutionally guaranteed special status, canceling its partial autonomy. Indian troops poured into the streets, the internet in Jammu and Kashmir was shut down for an extended period into the following year, phone service was cut and the media were severely restricted.

Today, there is an uneasy calm in the valley. People fear speaking out in public, press freedoms have been limited and local politics is dysfunctional and unresponsive to Kashmiris' everyday needs.

"While Indians celebrate their independence from [British] subjugation, they must also introspect as to what kind of union gets created by force," says Mirza Saaib Beg, a Kashmiri human rights lawyer. "And whether such forced unions merit celebration."

Opportunities have faded for diplomatic solutions

Zareef Ahmad's generation, born before India's Partition, remembers a time when a resolution to the Kashmir conflict seemed to be within reach. They hoped to see a return to self-rule.

"Kashmir is a nationality of its own, a civilization of its own, with more than 5,000 years of history," Ahmad says.

He lives in the older part of Srinagar, the largest city in Indian-administered Kashmir. His home is in an area surrounded by a Sufi shrine, a Hindu temple and a gurudwara, a Sikh place of worship.

"Kashmir's was always a composite culture, until India and Pakistan were divided on religious lines. We saw religion become a huge part of our division only after the countries were born," says Ahmad.

He and his generation expected a resolution to come from diplomacy and dialogue. The newly created United Nations got involved. India and Pakistan were initially led by statesmen like Prime Ministers Jawaharlal Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan. Kashmiris had their own leaders who exuded promise.

But in successive decades, the opportunities for a diplomatic resolution died a slow, painful death.

in 1953, India dismissed and then jailed the most charismatic Kashmiri leader, Sheikh Abdullah, as Kashmir's prime minister. "We felt betrayed," says Ahmed.

A hoped-for referendum to decide Kashmir's future never came.

"We extended a hand of friendship to India, but it cut our palm," says Ahmad.

Insurgency and army response

These days, Ahmad considers himself lucky to live with his son and grandsons.

"Not many Kashmiris have the joy of seeing their offspring alive — let alone live under the same roof," he explains. Violence and bloodshed have claimed the lives of many younger Kashmiris.

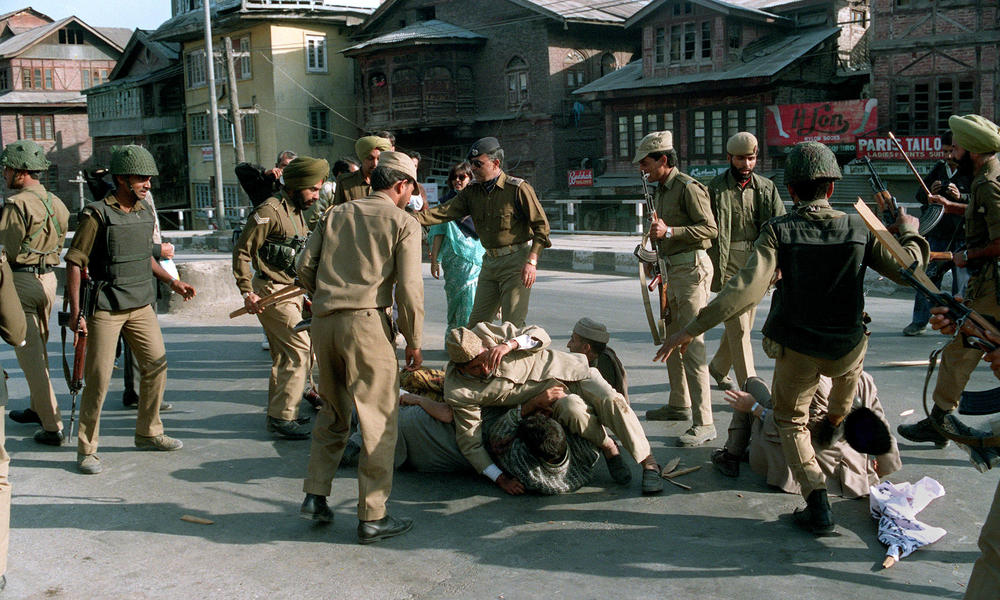

In the late 1980s, Kashmir exploded because the central government rigged elections in the region, argues writer and senior researcher Alpana Kishore. "The chief minister had been summarily dismissed, a puppet regime had been put in his place," she says.

Kashmiris lost faith in a secular, democratic India bit by bit, she says. The 1990s were arguably Kashmir's bloodiest years. According to official government figures, more than 1,700 were killed between 1990 and 2021 by armed guerilla fighters who are fighting the Indian state.

More than 150,000 people fled the area and resettled in other parts of India. While there are no official public figures on the number of people killed by India's security forces, Sweden's Uppsala Conflict Data Program puts the figure at around 19,000 for the same period.

"There have been so many bad memories in our schooldays, because those days, the violence was at its peak," said Shafkat Raina, Ahmad's godson, a documentary filmmaker who is 45 and grew up in Kashmir's restive Anantnag district.

He recalls ducking under the benches in his classroom as firing broke out between militants and the Indian army outside.

"Tension was not only in school, this tension followed us our whole life — whether it is married life or social life. It disturbed us, everywhere," he says.

As the militancy took on a religious color, most members of Kashmir's small Hindu population fled the region altogether, leaving behind jobs and property.

In light of the previous decades' diplomatic failures, many Muslim Kashmiris of Raina's generation believed for a time that a resolution to the Kashmir conflict could come from insurgency against India, with help from Pakistan.

Kashmiri youth illegally crossed de facto border, known as the Line of Control, into Pakistan to acquire weapons and to learn how to use them against the Indian military, which became a familiar presence in Jammu and Kashmir starting in 1990.

Militants "were praised. They were looked at like heroes," says Raina.

His neighborhood had two houses that militants occupied. "They used to come play cricket with us," he recalls.

"In the 1990s, there was great interest in Pakistan as a savior," says Kishore. "What happened [after the 1990s] is that [Kashmiris] understood that Pakistan is not going to go to war with India over Kashmir."

An uneasy "integration" with India

Those born in the 1990s or later are habituated with violence and conflict.

As India increased its military presence in Jammu and Kashmir, observers recorded an increase in torture and other human rights violations by security forces.

"Hundreds of civilians, including women and children, have been extrajudicially executed... Such killings and hundreds of deaths in custody — by far the highest in any Indian state — are facilitated by laws that provide the security forces with virtual immunity from prosecution," Amnesty International reported in 1995.

Today, it's difficult to know how many Indian security forces are stationed in Kashmir. The Indian government doesn't publish numbers. But troops are visible on most streets and public squares.

In a 2015 report, the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society estimated that there were between 650,000 and 750,000 Indian soldiers in the region. It's one of the most recent estimates available, as leaders of JKCCS have since been arrested.

Reaching the Pulwama district, in southern Kashmir, from Srinagar means crossing dozens of army checkpoints and barricades.

"Imagine being stopped many times and being asked for identification before reaching your own home," says Aamir Ahmad Bund, 25, a law student and president of the Association of Pellet Survivors, an organization for Kashmiris who have rubber bullets lodged in their bodies. He is among thousands who have lost their eyes due to attacks by India's military.

Bund was protesting in his village in Pulwama in 2016 when security forces fired rubber bullets, he says. The bullet that hit his right eye blinded him in that eye.

"There are several [rubber bullets] still lodged in my body," he says, pointing at his arms, torso and legs.

"No one even asks us what we think is a resolution to this conflict," he says.

With Jammu and Kashmir's limited autonomy broken in 2019, the government declared that the conflict was resolved and the region's integration with the rest of India was complete.

But for many Kashmiris, it has come at too high a price.

"When God asks me what I have, I will say I only have the trees I planted," says Ahmad, the poet. "Everything else is transient."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.