Caption

Police body camera recordings show interactions between Columbus police officers and Muscogee County Sheriff’s deputies during a conflict over booking prisoners at the jail in July 2022. A compilation was created from 13 different officers' recordings.

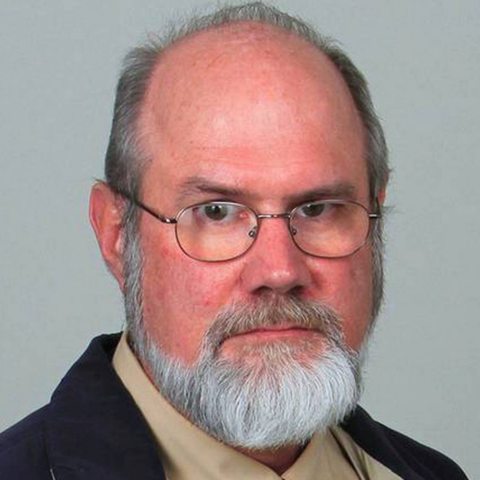

Credit: Mike Haskey / Columbus Ledger-Enquirer