Section Branding

Header Content

Discovering the forgotten women of silent cinema

Primary Content

Long before there were movie trailers to help people make their viewing decisions, there were these things called "lobby cards."

The hand-drawn images or photographic stills typically included a "title card" showing the name of the film and the key players involved, and then a number of "scene cards" showing key moments from the plot.

"Think of it as a static trailer," said Melissa Walker, curator of Experimental Marriage: Women in Early Hollywood, an exhibition of silent era lobby cards currently underway at Poster House in New York City. "These cards would have been posted in the window of a theater's lobby or . . . somewhere inside of the theater to promote coming attractions."

Experimental Marriage brings together around 90 lobby cards from a 7,800-item collection focused on women in silent film.

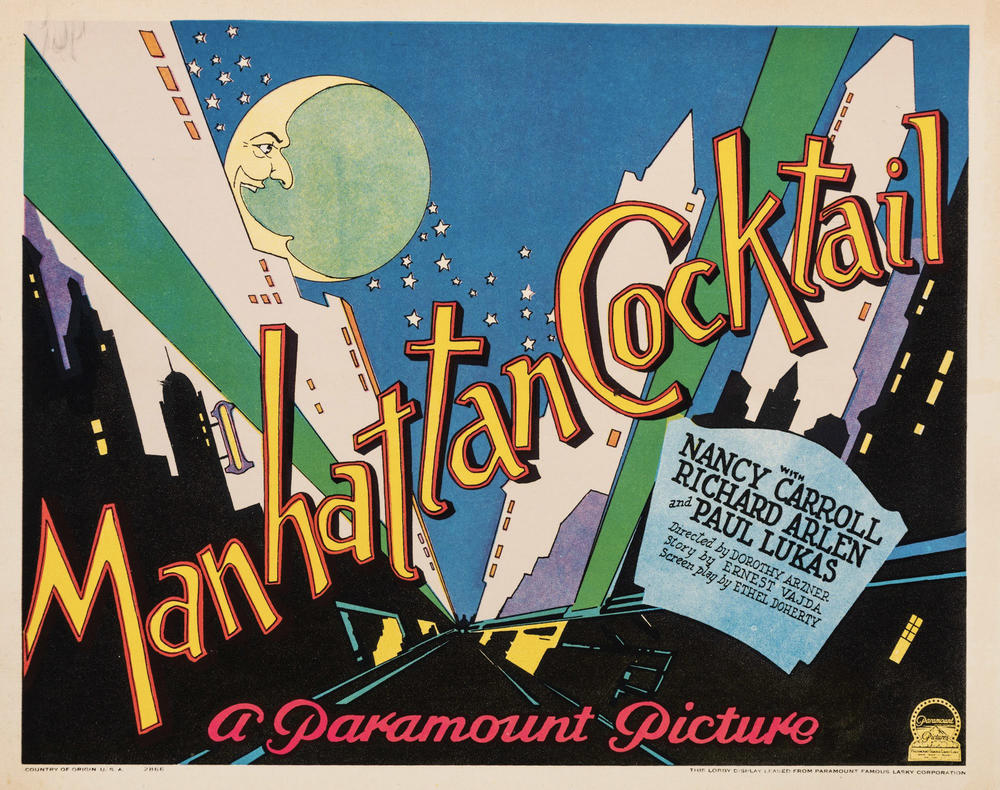

The items were gathered together by Chicago-based collector Dwight Cleveland, who has been collecting vintage movie posters and lobby cards for decades. A few years ago, while researching a book about movie posters, the collector zeroed in on a lobby card advertising Manhattan Cocktail, a 1928 Paramount picture directed by one of the most important filmmakers of the early cinema, Dorothy Arzner. The lobby card launched him into a deep, COVID-lockdown-inspired research project: He started tracking down publicity materials relating to the long-forgotten contributions of women involved in the U.S. silent film industry.

"These women played such a significant role as directors, producers, editors adaptors, writers and designers. I have a thousand names on my list that make up this filmography and some of them were involved in 50 or 75 films," Cleveland said. "I was kind of embarrassed after 45 years that I didn't know more about this."

The vast majority of silent-era movies are lost today, owing to fires, decaying film stock and other hazards. So the Poster House exhibition provides a rare insight not only into the breadth of female talent in the industry back then, but also the types of stories these women sought to tell on screen.

"The lobby cards and posters are the only surviving artifacts from those times for most of these films," said Robert Byrne, president of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival board and a film restorer specializing in the silent era. "They provide lone evidence of the people that made them and what those films represented."

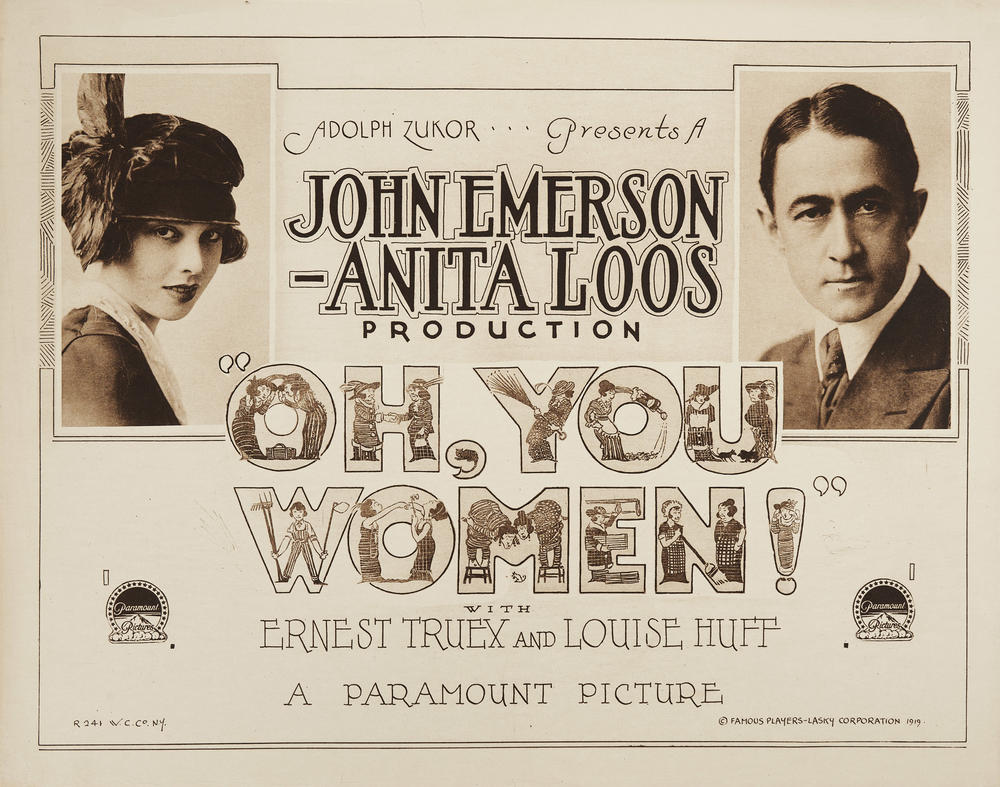

For example, the lobby card from the 1919 film Oh, You Women is significant for the prominent placement of the names and images of the film's writer-directors — wife-and-husband team Anita Loos and John Emerson.

"Their names are larger than the stars on this card. So that tells you something about the caché of these makers," said curator Walker.

Loos, a California-born actor and writer, was at the center of a pack of women movers and shakers in silent era Hollywood that included Marion Davies and sisters Norma and Constance Talmadge. Loos is perhaps best known now for her 1925 novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. She became one of the first women to earn a living as a staff screenwriter upon being hired by D. W. Griffith at the Biograph Company in 1912.

"I had been writing for Griffith for two years by mailing in scripts to his company," said Loos in a 1974 interview for NPR when she was in her 80s. "But by the time he became settled in Hollywood, he sent for me. And from then on, I remained on the lot as his staff."

Like many films of the era, Walker said the plot of Oh, You Women — which can be gleaned from studying the lobby cards — both played with and reinforced gender stereotypes. "A man has returned home to his hometown only to find it overrun with suffragists who are wearing pants," Walker said. "He falls in love with this woman who's wearing a dress. He falsely believes her not to be a suffragist."

Walker said she doesn't know how the film ended, as it's lost, and the lobby card collection is incomplete. But based on other titles targeted at a female audience during the silent movie era, she hazards a guess: "They probably get married in the end because that's a trend with all of these films."

The 1923 film Adam's Rib, one of relatively few silent era-films to still exist (it's accessible on YouTube) was directed by a man - Cecil B. DeMille. But women played other prominent roles on set. Writer Jeanine MacPherson, whose name can be seen at the bottom of the card, was a key figure in early film history. In addition to writing, she also acted in and directed movies.

"Jeanie McPherson worked a lot with Cecil B. DeMille. They did 40 films together," Walker said. "And when he died, it was suddenly then revealed that she was not only his coworker, but also his mistress!"

Walker added that the film included costumes by one of the era's most renowned costume and set designers, Clare West.

"Clare West is like a little bit of a hybrid," said Walker. "She had a really interesting job title at Triangle — studio designer."

The plot of Adam's Rib follows a wife's infidelity and a daughter's attempt to protect her mother's honor. Order is restored when the wife ultimately returns to her husband.

The exhibition also features scene cards from The Amazons, a lost film from 1917 starring Marguerite Clark. The cards are significant both because of what they show of the daring storyline — "It's about three sisters, and they were raised as men," Walker said — and as an example of the work of prolific screen writer Frances Marion, a longtime collaborator and friend of Hollywood icon Mary Pickford. "Marion wrote over 300 scripts, and in 1930, she became the first woman to win an Academy Award for writing a screenplay," said Walker. "And that was the first time a woman won outside of the 'best actress' category."

Marion is also notable as the co-author of How to Write and Sell Film Stories, which Walker said became required reading once universities started introducing film studies programs. "They adopted her book as a textbook," said Walker. "She was an authority."

Marion was one of relatively few women in Hollywood to have a lifelong career in the industry; she even has a posthumous credit from 1979 for creating the story for the Faye Dunaway-Jon Voight vehicle The Champ. But the overwhelming majority of the women who worked in Hollywood at the start of the last century did not go on to have extensive careers.

"In the early years, women were incredibly prominent because it was more of a cottage industry, where groups of people were contributing to all different aspects of making film in an informal way," said Radha Vatsal, a New York-based author, early film scholar and co-editor of The Women Film Pioneers Project, a digital sourcebook that catalogues women's contributions to early cinema. "Then the more the system developed, and the more it became professionalized, that's when women slowly got pushed out. The bigger the business, the less you're going to 'trust a woman' with making this product."

Vatsal said the contributions of women to early film in this country were all the more remarkable because so many of them made their mark before they even had the right to vote. She said it's taken nearly a century for the movie industry to gradually, and falteringly, bring women back into the leadership roles they once occupied in larger numbers.

"It's taken a long time for these numbers to recover again, and I'm not sure they completely have yet," said Vatsal. "I think we have a better understanding that progress isn't linear. You take many steps forward, but then you also take steps back."

Experimental Marriage: Women in Early Hollywood runs through Oct. 9 at Poster House in New York City, NY.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.