Caption

Olivia Coley-Pearson is a city commissioner in Douglas, the majority-Black seat of Coffee County, Ga.

Credit: Joseph Ross / Special to ProPublica

|Updated: September 14, 2022 8:55 AM

This story was originally published by ProPublica.

For nearly 10 hours on Georgia’s primary day, Olivia Coley-Pearson tracked down every potential voter she could find, working two cellphones as she paced the parking lot outside the polls, repeating the same message: “You need to tell all your cousins, your brothers, your sisters, your aunts, your uncles — everybody you know — to come on down here to vote.”

Olivia Coley-Pearson is a city commissioner in Douglas, the majority-Black seat of Coffee County, Ga.

A third of her neighbors in Coffee County struggle to read at a basic level, and she wanted to make sure they had help navigating their ballots. In the late afternoon, she slid behind the sparkly pink steering wheel of her SUV for her final push of the day, heading down a long stretch of road where buildings gave way to fields and thickets of pine. She turned in to the Kinwood Estates mobile home park and stopped at the edge of a familiar dirt driveway just as Shondriana Jones, 30, bounded down the steps of a trailer.

“I can’t find my ID and Mama, she’s still at work,” Jones said.

Coley-Pearson has helped the family vote for years — she’s known them since she and Jones’ mother, Sabrina Fillmore, were young. Now 60, Coley-Pearson serves as a city commissioner in Douglas, the majority-Black county seat. Fillmore, 54, works at the local poultry plant cutting chickens. Neither Fillmore nor her daughter can read beyond a first-grade level, but they rarely miss an election, believing their votes can influence everything from their electricity costs to the way police treat them.

Coley-Pearson urged Jones to track down a utility bill to prove her identity at the election office just as Fillmore returned from a 10-hour shift, exhausted. With the women aboard, Coley-Pearson started the car, anxiety brewing in her mind.

Even though federal law guaranteed the two women the right to have someone help them vote, Coley-Pearson knew too well that this right was under attack. For all of the recent uproar over voting rights, little attention has been paid to one of the most sustained and brazen suppression campaigns in America: the effort to block help at the voting booth for people who struggle to read — a group that amounts to about 48 million Americans, or more than a fifth of the adult population. ProPublica analyzed the voter turnout in 3,000 counties and found that those with lower estimated literacy rates, on average, had lower turnout.

“How the system is set up, it disenfranchises people,” said Coley-Pearson, who blames Southern political leaders for throwing up hurdles. “It’s by design, I believe, because they want to maintain that power and that control.”

Conservative politicians have long used harsh tactics against voters who can’t read — poor, often Black and Latino Americans who have been failed by the U.S. education system and who conservatives feared would vote for liberal candidates. Some states have required voters who needed help to sign an affidavit explaining why they need assistance; some have prevented voters who couldn’t read from bringing sample ballots to the polls and limited the number of voters that a volunteer could help read a ballot. Time and again, federal courts have struck down such restrictions as illegal and unconstitutional. Inevitably, states just create more.

Over the last two years, the myth of election fraud, supercharged by former President Donald Trump in the wake of his 2020 loss, has fueled a barrage of new restrictions. While they do not all target voters who struggle to read, they make it especially challenging for voters with low literacy skills to get help casting ballots.

Last year, Georgia passed a law limiting who can return or even touch a completed absentee ballot. Florida expanded the radius around election locations in which volunteers are prohibited from asking people if they need help. Texas passed a law prohibiting voters’ assistants from answering questions or paraphrasing complicated language on the ballot; a federal judge struck down several sections of the law in June. But the court left other provisions in place, including ones that increase penalties for helping voters who don’t qualify and require people who assist voters to fill out more paperwork. Texas did not appeal the decision.

To appreciate the impact of voter suppression, consider that recent elections have been determined by a narrow sliver of the electorate:

Despite losing the popular vote, Trump secured the presidency in 2016 by winning Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan by a margin of just under 80,000 total votes.

President Joe Biden prevailed in 2020 by winning Arizona, Georgia and Wisconsin by just over 40,000 votes combined.

Coley-Pearson recognizes the importance of this moment for Georgia, which is no stranger to close elections. Republican Gov. Brian Kemp faces another challenge from Democrat Stacey Abrams, and Sen. Raphael Warnock is attempting to hold on to his seat in a race that could tip the Senate back to Republican control. But to Coley-Pearson, helping people vote isn’t only about politics or even just about their rights as individuals. It is about the future of democracy at a time when it seems like the views of the majority are being marginalized by the actions of the few.

The Gladys Coley resource center in Douglas, Ga., is named for Olivia Coley-Pearson's mother.

A memorial plaque in Coffee County bears the name of Gladys Coley.

As a child in the 1970s, she’d watched as her mother, Gladys Coley — who stood just above 5 feet and had only an eighth grade education — rose to the helm of the local NAACP and challenged the discriminatory school system and police department. Her mother begged her not to return from college in Atlanta, but Coley-Pearson wanted to fight for the people of Coffee County, too. As she headed to the polls on primary day this past May, though, she couldn’t subdue her fear that by helping Jones and Fillmore, she was putting a target on her own back.

Over the course of several years, she’d become tangled in an investigation of supposed voter fraud, which took aim at her attempts to assist voters who requested help. She had pleaded her case to television cameras and at a hearing before the state’s highest election official. She had even wound up in jail.

“Intimidation is real,” Coley-Pearson said. “If we don’t continue to vote, they’re going to have us right back where it used to be.”

Coley-Pearson was born in an era when Southern states forced convoluted literacy tests on voters to keep Black people out of the polls. In those days, local voting officials often made exceptions for white people who couldn’t read. In 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act prohibiting racial discrimination at the polls. That didn’t stop white conservatives, especially in the South, from continuing to discriminate against voters with low literacy skills, who, due to centuries of oppression, were disproportionately Black.

An excerpt from a Louisiana voter literacy test that was in use around 1963.

Conservatives argued that removing barriers for voters who couldn’t read would allow the federal government to overrule states’ decisions on how to run local elections and would hand more votes to liberal candidates. Clearly, they said, voters with low reading skills would be easily swayed by anyone assisting them, leading to rampant fraud.

“Today the bureaucrats are issuing certificates to vote to people who cannot read the ballot nor even the instructions on a ballot or on a voting machine,” segregationist Alabama Gov. George Wallace declared in late 1965. “The left wing liberals need as many illiterates as they can get to vote in order to keep them in power.”

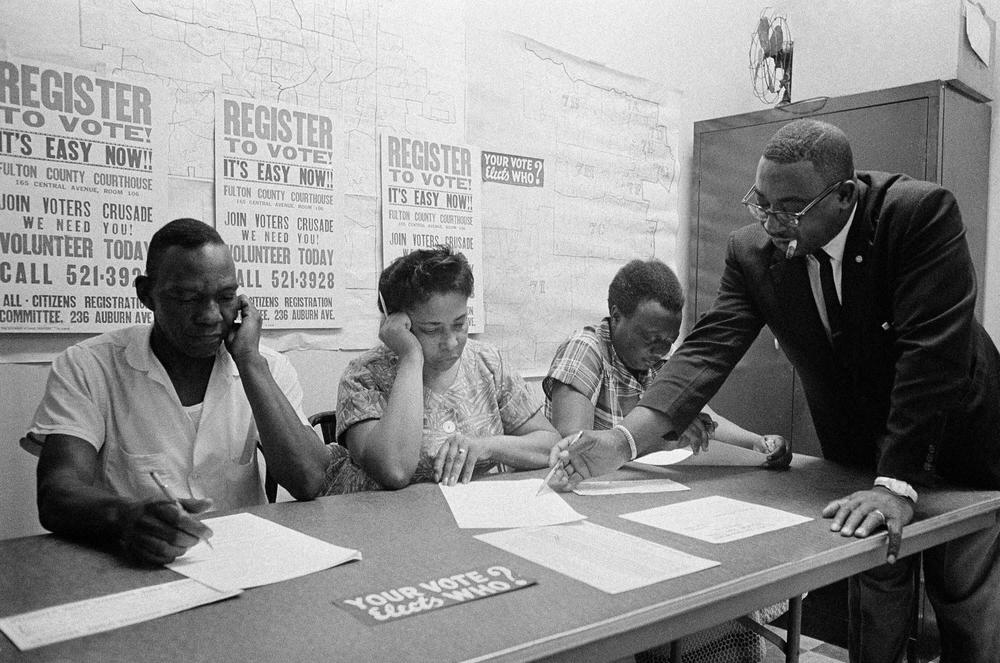

The Rev. Fred C. Bennette Jr., a civil rights movement organizer, right, instructs Black people in Atlanta how to fill out registration forms in 1963.

By 1981, voters of color, including those with low literacy levels, still faced “white resistance and hostility,” according to a U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report. “For many minority voters, the kind of assistance that they receive at the polls determines whether they will vote,” the report stated. “If minority voters who do not speak English or who are illiterate receive inadequate assistance, they may become too frustrated and discouraged to vote or they may mark their ballots in such a way that they will not be counted.”

Congress amended the Voting Rights Act in 1982 to affirm that voters who need help due to an “inability to read” could bring someone, other than their employer or union representative, to assist them in the voting booth. A string of subsequent lawsuits shows this federal action again failed to eradicate the discrimination.

In a 2001 case, the federal justice department claimed that white poll managers in Charleston County, South Carolina, were intimidating Black voters who requested assistance. According to testimony given in the case, the poll workers launched a barrage of questions at these voters, such as, “Can’t you read and write? And didn’t you just sign in? And you know how to spell your name, why can’t you just vote by yourself? And do you really need voter assistance?”

A federal judge found that there was “significant evidence of intimidation and harassment,” but said evidence of the mistreatment was too “anecdotal” to take direct action.

In 2012, the chairman of Coffee County’s board of elections filed a complaint against Coley-Pearson and three other residents, alleging that they’d assisted voters who didn’t legally qualify for help. Georgia law only allows voters to receive assistance if they are disabled or cannot read English. The secretary of state’s office, then under Kemp’s leadership, initiated an investigation.

Alvin Williams

The following summer, a 52-year-old line cook named Alvin Williams answered his phone to find a state investigator on the other end. The man had questions about the 2012 election. “It looks like you were assisted by Olivia Pearson,” said state investigator Glenn Archie, in a recording obtained by ProPublica. (Archie did not respond to a request for comment.) “It’s not marked why she assisted you and I was wondering why you needed assistance.”

The tone of the man’s voice made Williams nervous. “Because I can’t read. I’m illiterate,” Williams told Archie. He’d dropped out of school at 16 to work full time catching chickens and selling them to the local poultry plant, a job he’d skipped classes for since he was 11 to help support his family.

“I’m sure she read the candidates to you,” Archie said. “Did you get to pick the people you wanted to vote for?”

“Yes, sir,” Williams said. “I can’t read. That’s why she was helping me.”

“That’s no problem,” the investigator assured him. “She can assist you if you have problems reading.”

But the call left Williams humiliated and fearful of how his vote could be used against him or Coley-Pearson. “I don’t fool with the law,” he said in a recent interview. “And I don’t do nothing for them to fool with me.”

Some other voters told investigators that they had requested and received help even though they could read. The investigation found that Coley-Pearson and the other volunteers neglected to verify whether some voters qualified for help and incorrectly filled out forms indicating why voters needed assistance. It also found that election workers failed to include required information on many forms and turned them in without making sure they were accurate.

Testifying at a 2016 hearing chaired by Kemp, Coley-Pearson maintained that she hadn’t broken any laws. In response to a poll worker’s claim that she’d touched the voting machine, Coley-Pearson said she’d merely accompanied voters who had requested her assistance and stood by to answer questions about the process or read names on the ballot. She said she followed the instructions of the poll workers, signing forms when directed.

“If someone asks me for help, I felt an obligation to try to assist if I could,” she testified at the hearing, stressing that she never told anyone who to vote for. Coley-Pearson suspected there was a deeper significance to the investigation and told the board, “Sometimes things are done to try to maybe dis-encourage, or whatever, other people from voting, and I don’t feel like that is fair.”

The state election board chose not to recommend her case for criminal prosecution, but a local district attorney’s office prosecuted her anyway, which made national headlines in BuzzFeed. It charged her with two felonies for improperly assisting a voter and for signing a form that gave a false reason for why a voter needed assistance. The trial ended with a hung jury. One of two Black people on the jury told a local reporter that she was the only holdout; everyone else voted to find Coley-Pearson guilty. She was tried again in a nearby county and, after about 20 minutes of deliberations, the new jury acquitted her of all charges. The district attorney’s office did not respond to ProPublica’s emailed questions.

On the day of Georgia’s primary elections in May, ProPublica followed Olivia Coley-Pearson to capture what it takes to ensure that voters who need help can get it.

On the day of Georgia’s primary elections in May, ProPublica followed Olivia Coley-Pearson to capture what it takes to ensure that voters who need help can get it. Credit: Mauricio Rodriguez Pons/ProPublica and Zach Read for ProPublica

Three other volunteers took plea deals in which they admitted to making false statements on forms indicating the reason that a voter needed assistance; in exchange, they got probation, after which any fines would be waived. One of them, James Curtis Hicks, said that if he had fought his case and lost, he could have faced jail time or a mountain of fines. He didn’t want to take any risks. “Around here, to me, they target the leaders, the people that are standing up for the rights of the minority,” he said in a recent interview. “To shut me and Ms. Pearson down, it would stop a whole lot of people going to the polls.”

For years, the 59-year-old truck driver had kept tabs on Coffee County voters to see if they needed help reading the ballot. But after the settlement, he stopped. “I didn’t want a focus on me to suppress anyone else,” he said. “I really felt intimidated.”

But the charges didn’t deter Coley-Pearson.

Signs are seen in a voting rights demonstration in Coffee County.

Before Jones could vote that May afternoon, she needed to get temporary identification. Dodging the pouring rain, she and Coley-Pearson scuttled into the elections office shortly before it closed. At nearly 6 feet tall, Coley-Pearson towered over the woman sitting behind a plexiglass barrier.

“She needs a voter ID, sweetie,” Coley-Pearson said, leaning in. The woman handed Jones an application.

“You need me to do it, baby?” Coley-Pearson asked softly.

Jones nodded, “Yes, ma’am.”

The woman at the counter emphasized that Jones had to complete it on her own.

“She has trouble reading and writing,” Coley-Pearson said.

After a tense moment, the woman agreed that Coley-Pearson could fill out the form. She read the questions out loud and filled in Jones’ answers, pointing out which lines to sign and date.

Shondriana Jones.

Jones is in the third generation of her family that is not able to read. Her grandmother never learned how, and her mother, Fillmore, left high school in her sophomore year, after frequently being disciplined for fighting. As an adult, Fillmore briefly attended an education program to help her learn how to read, but she felt discouraged and left.

Jones graduated from high school in Coffee County but says she reads at the same first-grade level as her mother. She remembers attending special education classes with more field trips than written assignments and says teachers never diagnosed her with a learning disability or gave her one-on-one assistance. School administrators also frequently suspended her for fighting, she said. “They were trying to get rid of me.”

Coffee County has long failed to provide an equal education for students of color. In 1969, federal officials sued its school board for refusing to integrate white and Black schools. Even after the school system was integrated, Black students continued to receive fewer academic resources and harsher punishments than their white peers. A decade ago, the district acknowledged its shortcomings in reading instruction and the need to rectify its problems with literacy, which were more pronounced for Black students.

The county’s lower literacy rate is related to its high poverty rate, and since integration, the district has worked to increase opportunities for students of color, Coffee County School District Superintendent Morris Leis said in an email; he added that the district does not use discipline to “push out” children who have academic challenges, and it has reduced racial disparities in discipline after it initiated a new program in 2014. By that time, Jones had graduated.

She aspires to learn how to read through an adult education program and to eventually work at a child care center, but she cannot do so without steady transportation. She has not applied for a driver’s license; though she could take the written test orally like her mother did, she hasn’t been able to find someone who has time to help her study the examination booklet.

Ordinary tasks are often insurmountable for her. She owns a smartphone, but mining the web for information is daunting. After she fell several months behind on her electric payments, she could not read the notice that warned her lights would be cut off. She likely qualifies for low-cost internet, but she cannot navigate the instructions for accessing it. When she takes her son to the doctor’s office, she prints his first and last name on the forms but asks the staff for help with the rest. Unable to decipher her most valuable documents, like her birth certificate, she entrusts them to her aunt, who can read and helps determine what she needs for appointments and applications.

Jones worries most about keeping up with her 4-year-old son as he grows. She can read beginner books to him, but she knows his knowledge will soon surpass her own.

For Jones, the voting process itself is like a literacy test. If she changes her address, she cannot easily update her registration. If she enters the polling booth alone, she may recognize a few names on the ballot, but any unfamiliar words could confound her, particularly when it comes to the often-confusing constitutional amendments. She prefers voting by mail, which allows her more time to process her choices, but Georgia’s new election law is making that more difficult. The law has banned outside groups from mailing out absentee ballot applications that have the resident’s information already filled in, and it has limited who can submit the applications on voters’ behalf. The law does include exceptions for people helping “illiterate” voters, but experts say its limit on assistance could still discourage those voters from requesting help.

“Any law that limits assistance is going to have an impact on voters with limited literacy,” said Sean Morales-Doyle, acting director of voting rights at the Brennan Center for Justice. “Whether or not that’s the intention of the lawmakers, that’s always a difficult thing to say. But I do think sometimes it may very well be the intention.”

It is impossible to say precisely what role literacy plays in voter turnout. There are many other factors that contribute to lower participation, including some closely intertwined with literacy, such as income and education level. But to put the importance of reading ability in perspective, ProPublica analyzed data on turnout from the three most recent national elections and compared it to average estimated literacy levels for over 3,000 counties. (Read more about our analysis, and the data used, in our methodology.) Our analysis found that if low-literacy counties had turnout similar to high-literacy counties, they could have added up to about 7 million votes to the national total for each of those three elections.

Across the country, people like Jones are stumbling through inscrutable election processes fraught with poor ballot design and rigid registration rules. Some are choosing not to vote at all. (Read more about how some states are trying to make voting more accessible.) “We know in general that the more barriers we put in front of people, the lower the participation rate,” said Donald Moynihan, a professor of public policy at Georgetown University. “Even if someone with lower literacy has the same desire to vote as someone reading this article, they have to overcome more barriers.”

In 2014, for example, Ohio legislators began requiring voters to fill out more complicated versions of absentee and provisional ballot forms while at the same time limiting the assistance they could get from poll workers. Minor errors in the paperwork could lead to people’s votes not being counted. In a lawsuit, the Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless claimed that the laws disproportionately harmed poor, nonwhite and low-literacy voters who would be more likely to have their ballots rejected for minor errors.

Data submitted as evidence shows that thousands of forms were tossed in the 2014 and 2015 general elections for simple problems such as incomplete addresses and birthdays. Poll workers refused one form because the street name “Cuthbert” was misspelled as “Cuthberth.” Several others were rejected because birth dates were listed as the current date, an indicator that voters may not have understood the instructions.

READ MORE

In 2016, a federal judge struck down the measures, concluding they disproportionately harmed Black voters. The 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed that state rules requiring perfect completion of absentee ballot forms posed an undue burden to voters. But the panel said the other measures were minimally disruptive and left in place regulations that limited the assistance voters could get from poll workers and the amount of time voters were given to correct errors on absentee and provisional ballots.

“What the case demonstrates is the indifference of officials from one political party, and of unfortunately many federal judges, to voting rights and to the need to make voting not only secure, but relatively unburdensome,” said Subodh Chandra, an attorney for the plaintiffs.

A similar law in Georgia suspended voter registration applications when the information on the form didn’t exactly match a driver’s license or social security record. (If voters didn’t correct the information within 26 months, Georgia could cancel their registrations.) When then-Secretary of State Kemp ran for governor against Stacey Abrams in 2018, his office suspended the applications of an estimated 53,000 voters, most of them Black, due to these discrepancies. Kemp won the election by about 55,000 votes.

A federal judge ordered Georgia to ease the restrictive program, calling it a “severe burden” on some voters. Politicians, academics and advocates have accused Kemp of voter suppression not only for suspending registration applications over minor discrepancies, but also for purging tens of thousands of infrequent voters from the rolls — a more aggressive effort than is made in other states.

Kemp press secretary Katie Bryd disputed the allegations and noted that Kemp had implemented automatic voter registration through the state’s department of motor vehicles in 2016, which added hundreds of thousands of eligible voters to the rolls. “Politically driven, irresponsible accusations of voter suppression alleged at Governor Kemp have been repeatedly found void of basic facts and validity,” Byrd said in an email.

Today, voters flagged for minor discrepancies in their registration paperwork can no longer be removed from the rolls, but they do have to show a photo identification before they vote.

A voting sign in Coffee County is seen.

As Coley-Pearson parked at the polling station, her thoughts flew back to a similar day not long ago when she wound up handcuffed in the back of a police cruiser.

In October 2020 — more than two years after she was cleared of the felony charges — she was standing in a voting booth helping a young woman with low literacy skills read a ballot, as is allowed by law, when the county’s election supervisor, Misty Martin, confronted her. Martin yelled at Coley-Pearson to not touch the machines and told her she was barred from returning to the polls. Coley-Pearson said she wasn’t touching any machines. “We’re done,” she told the young woman after she finished voting. “Let’s go.”

Martin, who also has used the last names Hampton and Hayes, called the police to report that Coley-Pearson was disruptive, and the department issued a trespass warning barring her from the polls indefinitely. Later that morning, when Coley-Pearson returned to drop off another voter, she was arrested in the parking lot and charged with criminal trespassing. The Georgia Bureau of Investigation is looking into election interference claims in Coffee County, including an incident in which Martin allowed several computer experts connected with Trump’s efforts to challenge the 2020 results into her offices, where they may have had access to election systems; Martin resigned from her county post under pressure last year. She did not respond to ProPublica’s questions related to either incident.

The charge hung over Coley-Pearson for nearly two years; this past June, a state judge agreed to drop the case if she signed a consent order agreeing to follow election law. “There was no evidence of any crime here,” Coley-Pearson said. “It feels like you’re fighting a losing battle.”

Her daughters see how the last several years have worn her down. AiyEsha Coley said she would sometimes wake up at 4 a.m. to feed her newborn and would find her mother on Facebook, reading through disparaging comments. Her daughters have long campaigned for her to retire from city commission, scared that the stress might eventually kill her. She’s starting to come around, and she plans to leave her post next year.

Now peering into her back seat, Coley-Pearson worried her presence could interfere with Jones and Fillmore’s ability to vote. “I did not want any type of confrontation, I did not want any kind of accusations, I just didn’t want any hassle,” she said.

She told them she would not be going in with them and instructed two close friends to help them instead. “When you get through, you all come down there to the tent,” she said, motioning to where her volunteers were sitting out of reach of the rain.

Coley-Pearson watched the women shuffle into the building and fretted as she waited, leaning on her mobile walker at the edge of the parking lot with a group of volunteer canvassers. She had reminded her friends of the rules, but she knew that sometimes, following them was not enough. “They might try to look for anything they could use against them,” she said.

After nearly an hour, Jones and her mother emerged, beaming.

Coley-Pearson’s nerves settled, at least for the moment.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with ProPublica.