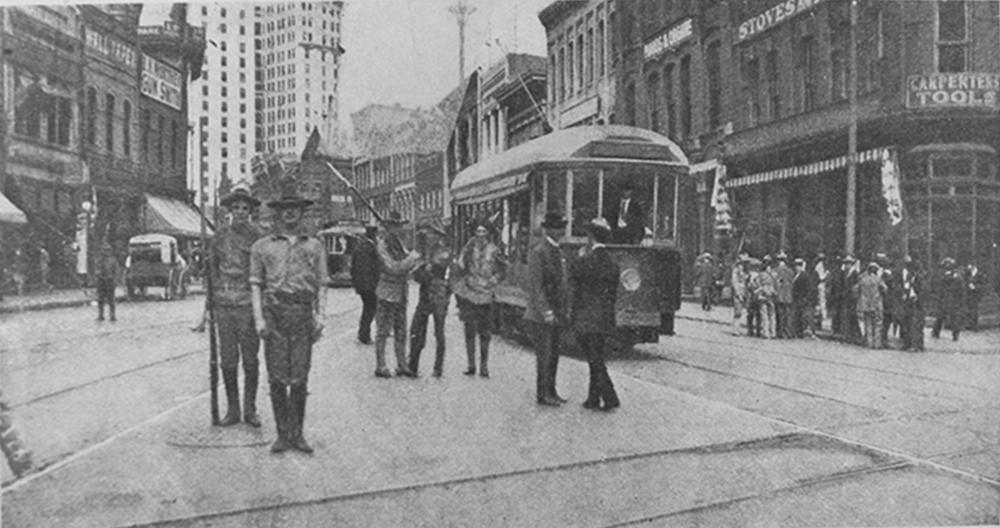

Caption

View of militia at the scene of the 1906 race massacre at the intersection of Walton Street and Peachtree Street in Atlanta, Georgia taken from Harper's Weekly.

Credit: Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center. Used by Permission.