Section Branding

Header Content

Savannah surpasses other police departments in solving murders. Why?

Primary Content

Jake Shore, The Current

As violent crime and killings are on the rise across the United States, Savannah has become a symbol of success in one vital metric: The city’s ability to solve homicides far exceeds the national average, according to police statistics.

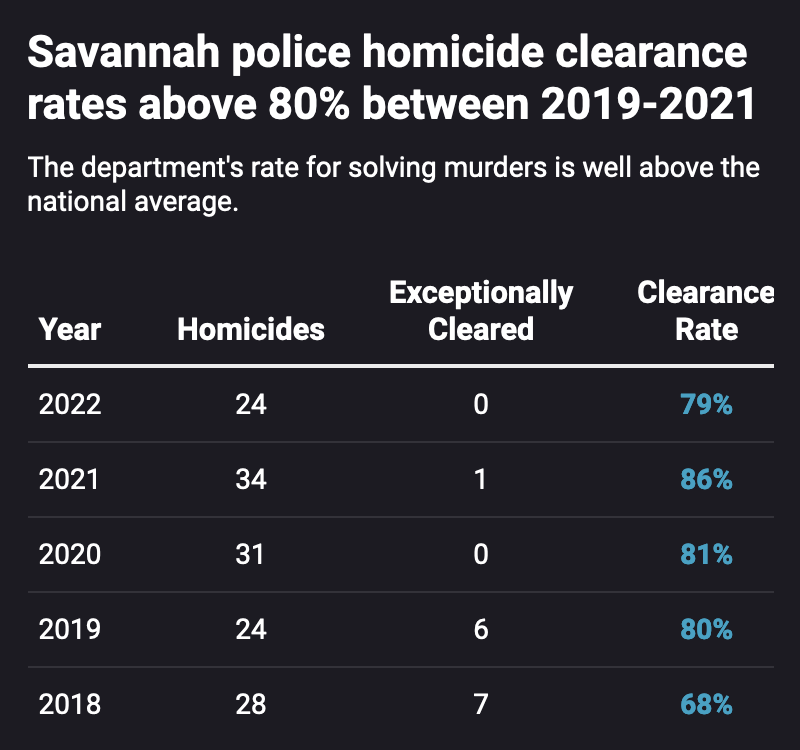

From 2019-2021, Savannah Police Department homicide clearance rates — the rate at which crimes are solved by police — were above 80% for each year. So far in 2022, detectives have a clearance rate of 79%.

The statistics outperform police departments in bigger cities like New York and Los Angeles, where homicide clearance rates in 2020 were 27% and 55% respectively, according to data. Cities similar in size to Savannah like Charleston, S.C., reported a 59% clearance rate, and Knoxville, Tenn., had 37% in 2020.

Lt. Zachary Burdette, who oversees Savannah’s homicide unit, says his team’s numbers reflect the quality of his officers and their operating procedures as well as trust they have among the communities where killings occur.

“They’re tenacious, once they get the phone call that there’s been a homicide. Their main goal is to get justice for the victim,” Burdette said of his team, which is made up of two sergeants and eight detectives.

The snapshot of successful detective work is a mark of pride for a department that has struggled in recent years with morale inside the force and its ability to foster community good will. Yet behind this important metric, the force faces steep challenges to stem gun violence and increase the perception of safety in Georgia’s oldest city.

To some public safety experts the statistic carries little weight, given the perception of rising violent crime in Savannah and Chatham County.

Who is killing whom in Savannah?

While some gun crimes, such as aggravated assaults, are on the rise in the city, homicides in Savannah have remained largely consistent through the years and have dropped from a peak of 53 in 2015, according to data.

So far in 2022, there have been 24 reported homicides.

In 2021, the police department recorded 34 homicides and in 2020, there were 31 homicides.

In the last 35 years, FBI crime data shows the highest amount of murders reported in Savannah was in 1991 with 59 homicides.

The U.S. murder rate fell by around 50% between 1991 and 2014, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

To analyze the reasons and context behind Savannah’s homicides in 2022, The Current compiled a list of the killings, obtained copies of police reports and indictments, and interviewed police officials.

So far in 2022, 45 % of Savannah’s homicide victims have been under the age of 25. Eight of them were 18 years old or younger.

Almost all of the suspects charged with murder this year were Black men.

Homicides occurred across the city, but a few were concentrated: two in Yamacraw Village, two in the Historic District, and two in West Savannah.

Like most U.S. cities, the majority of killings in Savannah happen by guns.

The Current filed an open records request to the Savannah Police Department for all reports from this year’s homicides. The department responded by providing initial reports sparse on detail.

What the police see

Lt. Burdette said Savannah’s cases didn’t reveal definitive trends. Most murders, he said, are between people who know each other and are not random acts.

An exception, he said, was a road rage incident at Bull and Broughton streets at around 2:30 a.m. on May 8. That resulted in murder charges for a 23-year-old man.

Burdette said most of the guns used in homicides this year were not reported as stolen.

Like many states, Georgia has seen gun sales spike in the past three years. According to data compiled by The Trace, close to 650,000 guns were purchased in Georgia in 2020, more than the amount bought in 2018 and 2019 combined.

In April 2022, Georgia legislators relaxed restrictions, allowing most anyone to carry a gun publicly without a permit or background check necessary.

Burdette said homicides involving gangs were “not a large number” of cases in 2022.

A Savannah police car parked outside the department’s headquarters on Habersham Street on Aug. 17, 2022.

That’s a change from when former Savannah Police detective Robert Santoro supervised the homicide unit. He said neighborhood groups and gangs were “a big part of a lot of our violence” during his 11 years on the force. He left the department in 2020.

According to Burdette, increased access to guns means an increased possibility of altercations becoming violent.

“The idea of, you know, teenagers and young adults carrying guns instead of just … doing things the way we used to do (fighting),” Burdette says, “It blows my mind every single time that we have one of those.”

Best practices

Santoro, who now works as a detective in law enforcement in the Midwest, said the Savannah department has quality detectives and has done well to recruit officers from different precincts to the unit.

According to Burdette, the unit’s structure promotes collaboration.

“Anytime there’s a homicide, during normal business hours, everyone at work goes,” Burdette said. “Once they’re done with the scene, they get in (and) they all have partners.” It’s so one detective is a check on the other one and that no information will be missed, he says.

Problems with measuring clearance rates

Good detective work has resulted in quick arrests among many of Savannah’s violent killings. But measuring clearance rates, however, can be a problematic way to measure police department performance.

Although police have reported a 79% clearance rate for 2022, that number includes arrests made in the calendar year for murders from past years.

Excluding arrests from past years, in 2022, there has been at least 1 arrest in 14 homicide cases out of a total of 24 homicides, according to an analysis by The Current.

Another problem with clearance rates, according to Philip Cook, a researcher at the University of Chicago Urban Labs, is that police don’t typically include homicides in which police officers are the alleged shooters.

Savannah PD does not include officer-related shootings in its clearance rate unless “they result in indictment from the (District Attorney’s) office,” police spokesperson Bianca Johnson said.

Savannah officers have been involved in five shootings in which victims have been killed this year. Each incident is still under investigation and they are not included in the city homicide rate.

None of these police-involved shooting cases have been cleared, as Chatham County District Attorney Shalena Cook Jones hasn’t announced prosecution decisions.

Historic killings sometimes stay unsolved

Savannah Police’s emphasis on above average clearance rates doesn’t impress Janice Hall.

Her son Curtis,, 32, was killed in west Savannah on January 20, 2011. His killing remains unsolved, and his mother still struggles with closure.

“Pretty much, it feels like it didn’t happen,” Hall said . “But it did happen.”

Curtis was found with gunshot wounds between New Castle and Comer streets. Police told Janice that there was an altercation and her son was running away when he was killed, Hall said.

He wasn’t a perfect person, Hall said, but her son was the father of five girls. He would call his mother three to four times a day, she said. Their family cooked dinners to sell and he would help sell their meals, Hall said.

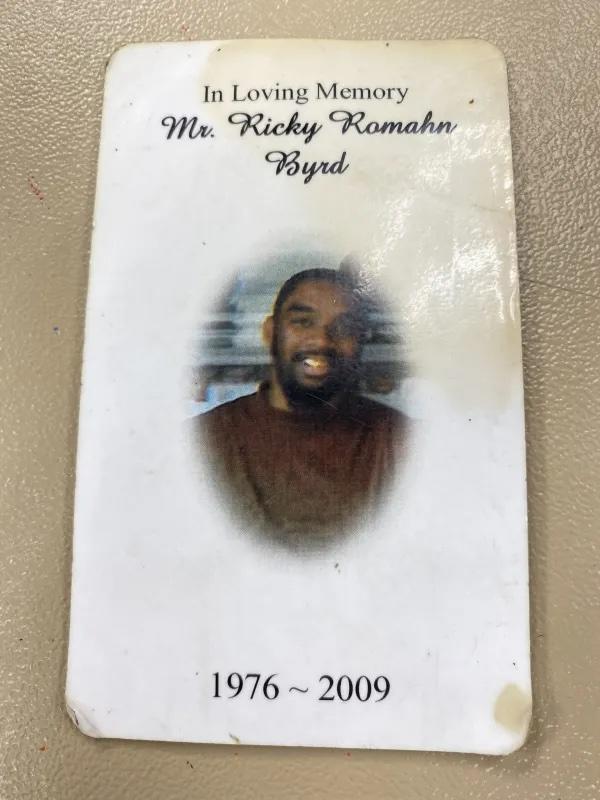

Maggie Mainor, sister of Ricky Byrd, who was killed in east Savannah on Hawthorne Street in April 2009, said her family has the same open wound from Byrd’s unsolved death. Mainor is also the aunt of Alan Mainor, a Savannah pastor who has been advocating for police reform.

Mainor said she had to keep pushing the homicide unit for updates on her brother’s case.

“They probably called me about three or four times,” Mainor said. “But most of the time I called them. I would call them once a week. I was getting aggravated with them.”

Not long after their family member’s killings, for Hall and Mainor, the calls eventually stopped and the leads went dead.

They rekindled some hope after the Savannah Police Department formed a cold case unit in 2016 under then-Chief Joseph Lumpkin.

It’s staffed by three part-time detectives, and they are assigned cases for follow-up by homicide sergeants, according to police spokesperson Johnson.

“The sergeants identify open cases with new leads or cases that may benefit from newer forensic technology. The unit is also assigned cases to review to see if they can determine” if anything was missed in the initial investigation, Johnson said.

Savannah police spokeswoman Johnson said the department has no updates on the Curtis Hall and Ricky Byrd cases.

When Hall hears about the Savannah Police Department’s high clearance rates, she wishes police would investigate cold cases with the same vigor as the new cases that come in.

“They say put fresh eyes on evidence and stuff like that, you know, on these cases, but to no avail,” Hall said. “Nothing coming from that for me.”

Reaching conviction

Sometimes, however, the slow, steady pace of detective work pays off.

Lawrence Bryan IV, 23, was shot to death in a botched robbery on Aug. 7, 2015, while coming out of an east Savannah apartment where he and a friend were gambling.

For Linda Wilder Bryan, it took a year-and-a-half after her son’s death for Savannah’s homicide unit to make a breakthrough. They finally identified and charged a 25-year-old Savannah man with murder..

Timone Hooper had been serving a federal prison sentence when he was charged.

Bryan credits former detective Santoro with dedication to the case.

“I was on the phone with him every day, all day, twice a day,” she said. “I was (saying) ‘what’s going on?’”

Santoro and the homicide unit used cell phone data to trace Hooper to the scene of the armed robbery.

Hooper was sentenced to life in prison for murder.

Through the experience, Alderwoman Bryan said her family became very close to Santoro and his family.

Now, Bryan is the godmother to Santoro’s children, she says.

“He was genuine, very humble, just a spitfire,” Bryan said. “And I just love him dearly.”

Bryan recognizes not everyone has as positive experience as she did with Savannah Police.

Bryan, who is now a serving councilwoman, said she hopes the department, under the leadership of Interim Chief Lenny Gunther, doesn’t rest on its laurels from the homicide unit’s clearance rates.

“I would want it to be 100%,” Bryan said. “So wow, that is a good number but it is not good enough. They need more detectives in that area and [with] cold cases.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.