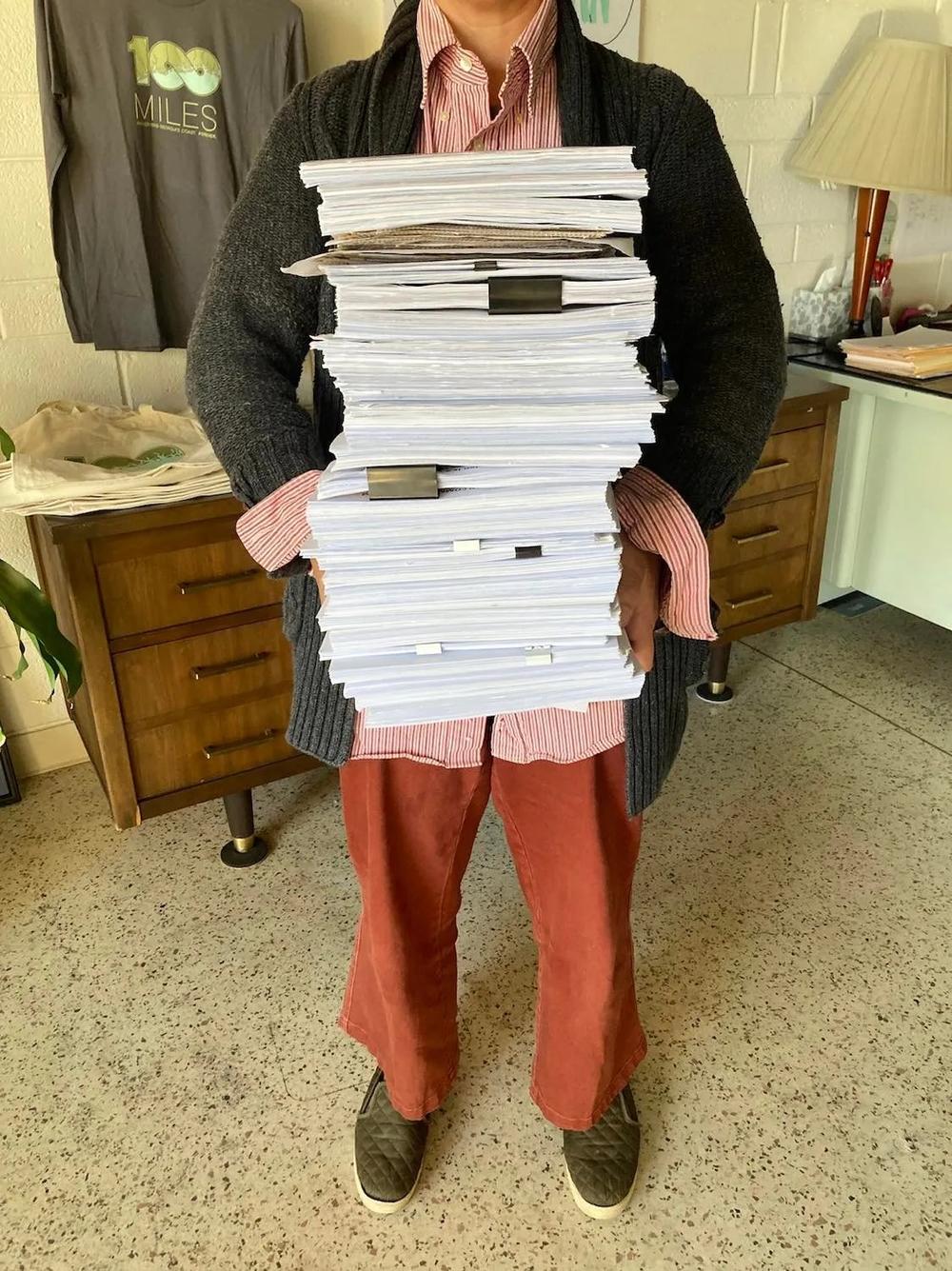

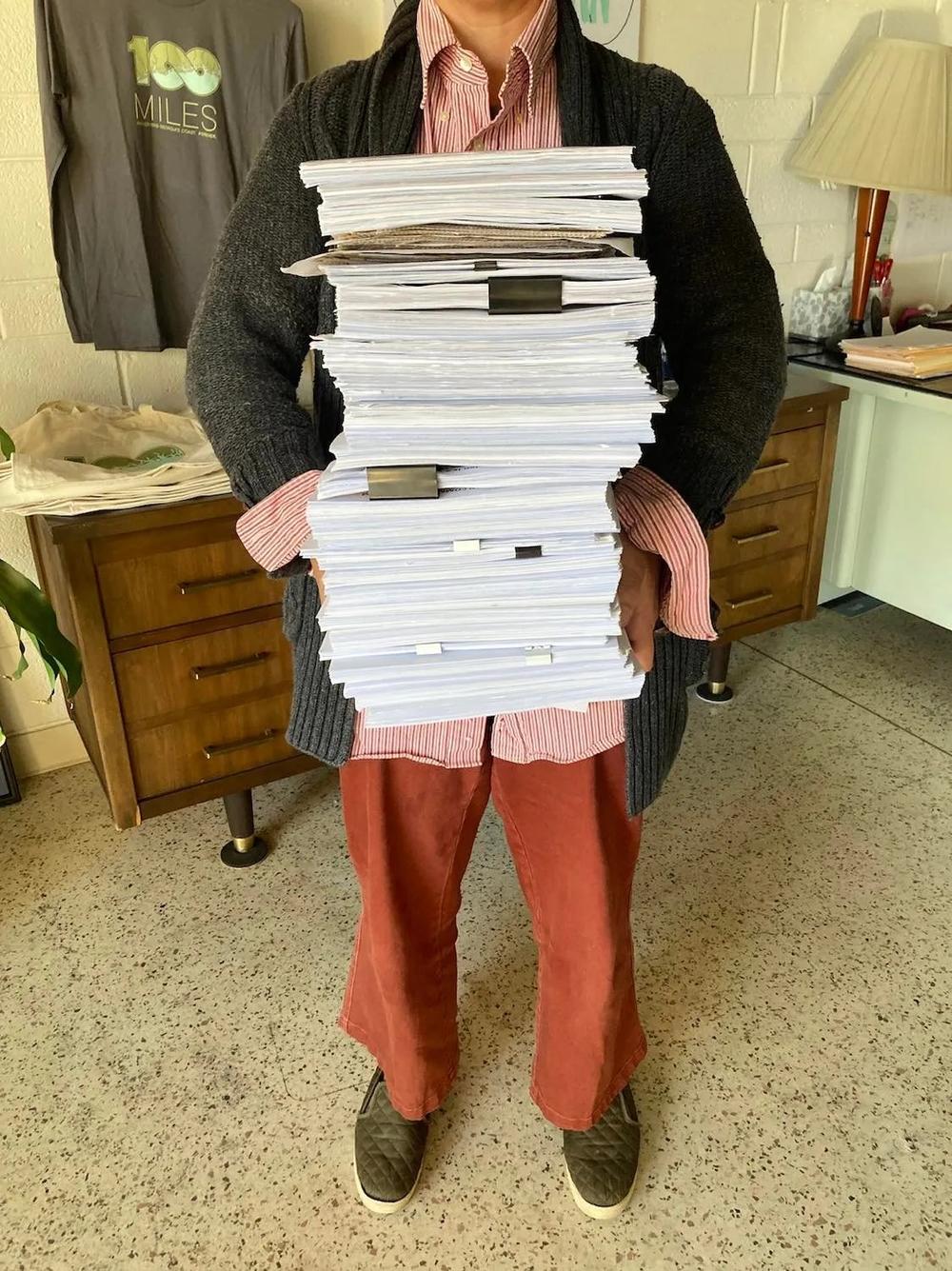

Caption

Megan Desrosiers holds the stack of petitions collected to force a referendum on the purchase of land for Spaceport Camden.

Credit: One Hundred Miles

Megan Desrosiers holds the stack of petitions collected to force a referendum on the purchase of land for Spaceport Camden.

Mary Landers, The Current

When a group of Camden citizens decided they were fed up with the county’s plan to develop a spaceport, they turned to the Georgia Constitution for a plan of action. There they found what they believe is a blueprint for recalling a county government action: Write a petition, get 10% of the county voters to sign it. Then, have a judge vet the signatures to trigger a referendum on the issue.

County residents like Jackie Eichhorn had already tried to talk officials out of the plan, first announced in 2015, to launch rockets from a former industrial site over residential property on nearby Cumberland and Little Cumberland islands. She wrote letters to the editor, made public comments at County Commission meetings and submitted written and oral public comments to the Federal Aviation Administration, which had to approve licensing for Spaceport Camden.

Camden resident Jackie Eichhorn comments at a June 2022 Camden County Commission meeting.

But the licensing process kept progressing. So in 2019 spaceport opponents began collecting signatures. By December 2021, after the county had spent more than $10 million on the spaceport plan, petitioners reached their 10% goal and submitted the signatures to the local Probate Judge Robert C. Sweatt, Jr. At the same time they requested an injunction to prevent the county from buying the spaceport property until after the referendum.

The following week the FAA issued a launch site license for the spaceport, contingent on the county purchasing the Union Carbide site it planned to develop as the launch facility.

A series of court battles ensued. Ultimately, the petitioners prevailed. The property sale was postponed and the referendum was held March 8. Spaceport opponents won by a nearly 3-1 margin.

County officials immediately discounted the vote, saying too few voters participated. But at 17%, the turnout was on par with other single issue elections in Camden. (Only 7% of the county electorate voted in the 2019 Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax initiative.) The county appealed the election’s validity to the Georgia Supreme Court, arguing the constitutional provision regarding petition-driven referenda doesn’t apply in this case. The case is officially Camden County vs. Judge Robert C. Sweatt, Jr., and James Goodman and Paul A. Harris, the latter two being intervenors on behalf of Sweatt.

The Georgia Supreme Court will hear the case Thursday, Oct. 6, in Augusta.

Camden County Commission Chairman Gary Blount chats with County Attorney John Myers as Probate Court Judge Robert C. Sweatt Jr. sits off to the left waiting for a hearing to begin earlier this year.

In the meantime, property owner Union Carbide announced it’s no longer interested in selling to Camden and isn’t contractually obligated to do so. The county disagreed and is suing Union Carbide, a subsidiary of Dow Chemical Co., one of the largest chemical companies in the world. That separate case is proceeding in U.S. District Court in Brunswick.

On Thursday, each side for the state constitutional case will present its case backed up by one friend of the court brief.

The petitioners based their actions on the “Home Rule” provision of the state constitution that allows for repeals of county resolutions by a petition containing signatures from 10% of registered voters in a county Camden’s size, which is over 50,000. “In the event the judge of the probate court determines that such petition is valid, it shall be his duty to issue the call for an election for the purpose of submitting such amendment or repeal to the registered electors of the county for their approval or rejection,” Article IV, section 2 of the constitution reads.

A voter enters the polling place at Woodbine City Hall during the March 8, 2022, referendum on the county land purchase for Spaceport Camden.

The petitioners argue in their brief that the plain language of the Constitution supports their actions.

The county argues the petitioners misconstrue the Home Rule provision, saying it’s more complicated than that and allows the electorate to repeal only certain types ordinances, resolutions and regulations, namely those that effect a change to state law.

The Association of County Governments of Georgia weighed in with a friend of the court brief saying the issue is important to its members, the 159 county governments of the state.

“Should this Court rule in Respondents’ favor on this issue, the consequence will be cycles of actions by elected county and city governing authorities, followed by voter petitions to overturn those actions, then new local government actions and potential new petitions/referenda — all in contravention of the constitution’s establishment of governance by a county governing authority as the elected representatives of its citizens, they write in their brief.

Larry Ramsey

Despite now anticipating a flurry of challenges to county decisions should the spaceport referendum stand, one of authors of the brief in February told The Current that an attempt like that of the Camden petitioners was rare.

“I can’t tell you of a similar situation either about a voter referendum to overturn a county decision,” said Larry Ramsey, general counsel of the Association of County Commissioners of Georgia. “This is the first time I’ve seen this go that far.”

The University of Georgia School of Law First Amendment Clinic and the Georgia First Amendment Clinic, along with petition organizers Jackie Eichhorn and Ben Goff, who’s running as a write-in candidate for county commission, wrote a friend of the court brief in support of the intervenors James Goodman and Paul Harris.

They argue that “Democratic principles that animate the First Amendment right to petition equally undergird the Georgia Constitution’s county referendum power” and “The referendum power provides voters with a nuanced interim remedy during non-election years.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.

——

The four briefs related to the case Camden County, Georgia, Petitioner-Appellant, v. Robert C. Sweatt Jr., respondent-appellee, and James Goodman and Paul A. Harris, intervenors-appellees are available at the following links:

Camden County’s principal brief was written by County Attorney John Myers and attorneys William B. Carver, Russell A. Britt and Pearson K. Cunningham of Hall Booth Smith PC in Atlanta.

The Association of County Governments of Georgia’s brief in support of Camden County was written by ACCG attorneys Larry Ramsey and G. Joseph Scheuer.

Appellant’s reply brief is here, also written by Myers and the attorneys at Hall Booth Smith.

The response brief from appellee Judge Robert C. Sweatt Jr. was written by attorney Kellye C. Moore of Perry-based Walker, Hulbert, Gray and Moore.

The intervenors’ response to Camden’s brief was written by attorneys Dana Braun, Kimberly Cofer Butler and Philip Thompson of the Savannah firm Ellis Painter.

The friend of the court brief in support of the intervenors and appellee was written by Clare R. Norins of the UGA Law School First Amendment Clinic.

Reporter’s note: This article was updated on Oct. 4 with links to two previously omitted briefs and to correct the names of the intervenors, James Goodman and Paul Harris.