Section Branding

Header Content

Jaime Jarrín is going, going — kiss him goodbye!

Primary Content

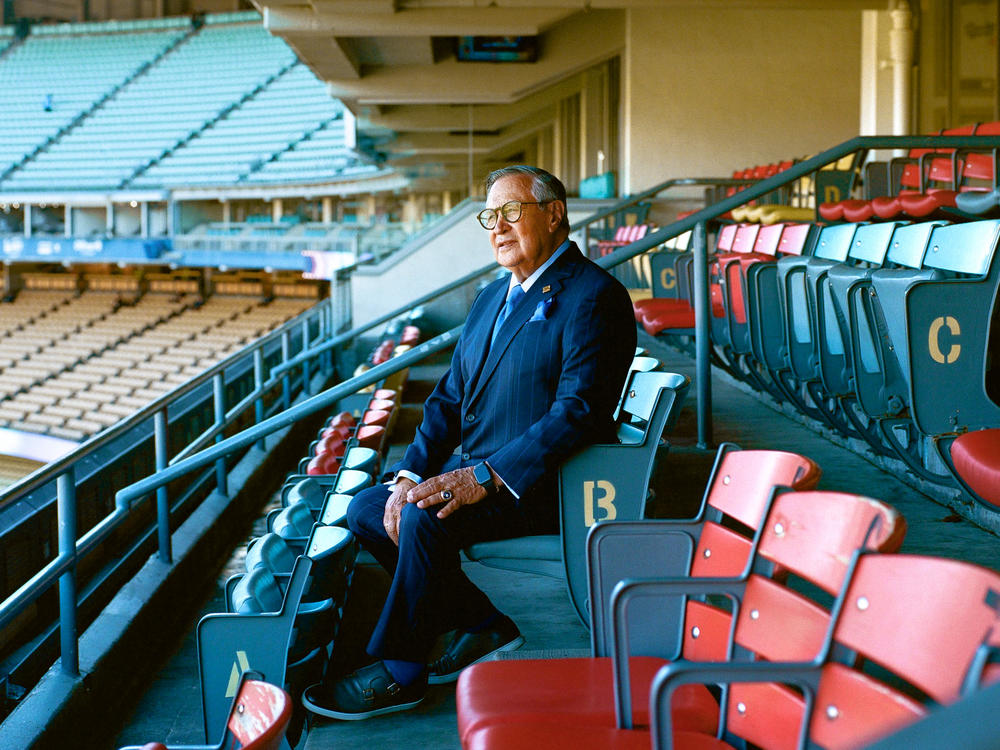

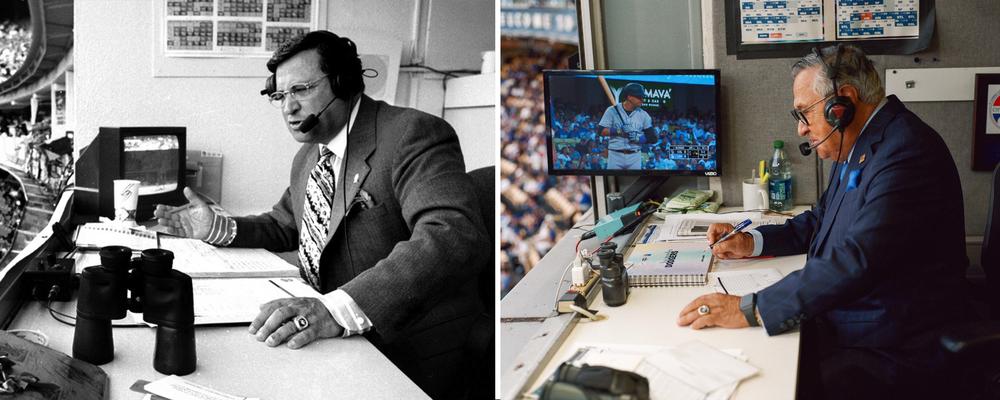

Jaime Jarrín has done the same job, at the same company, for the past 64 years.

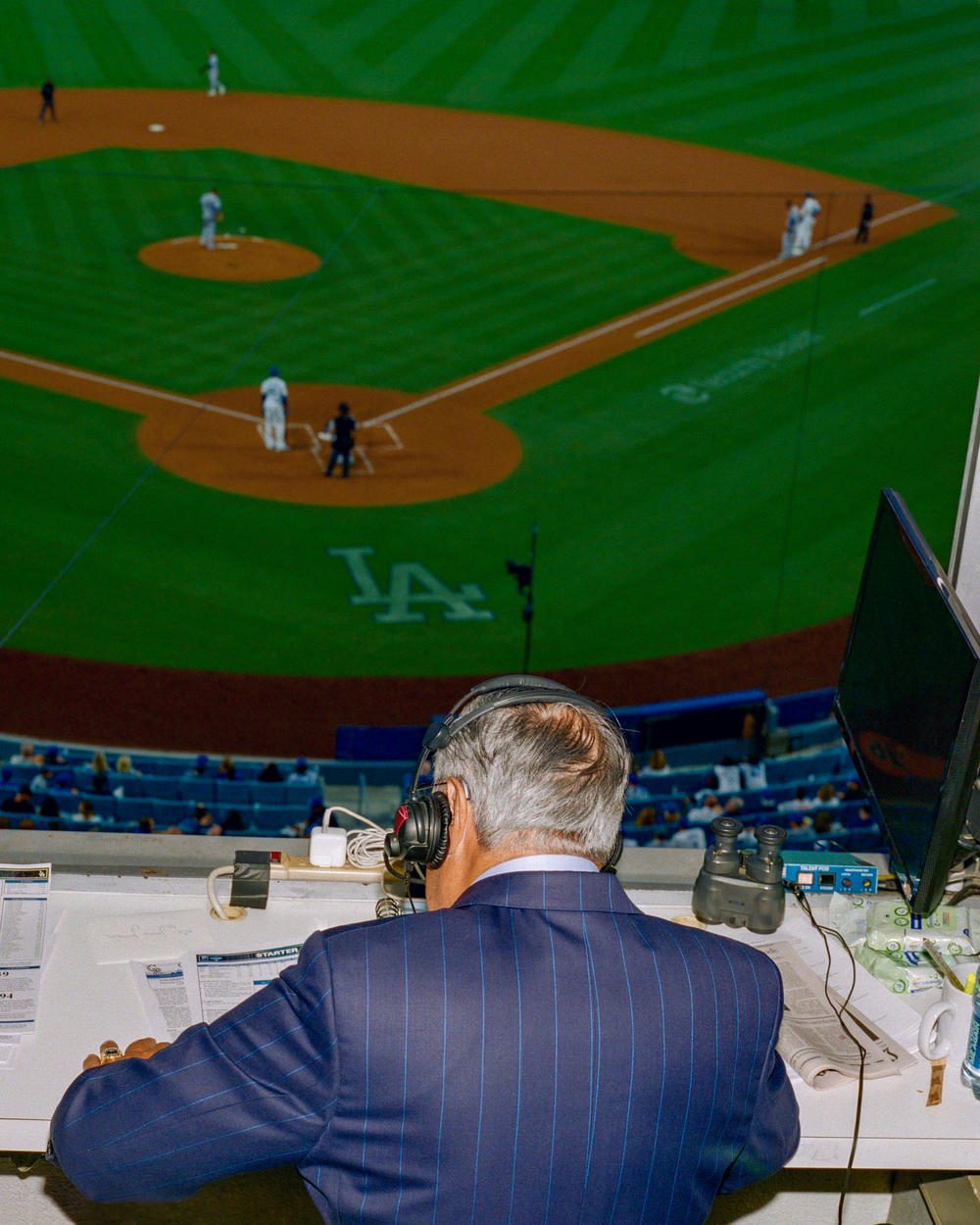

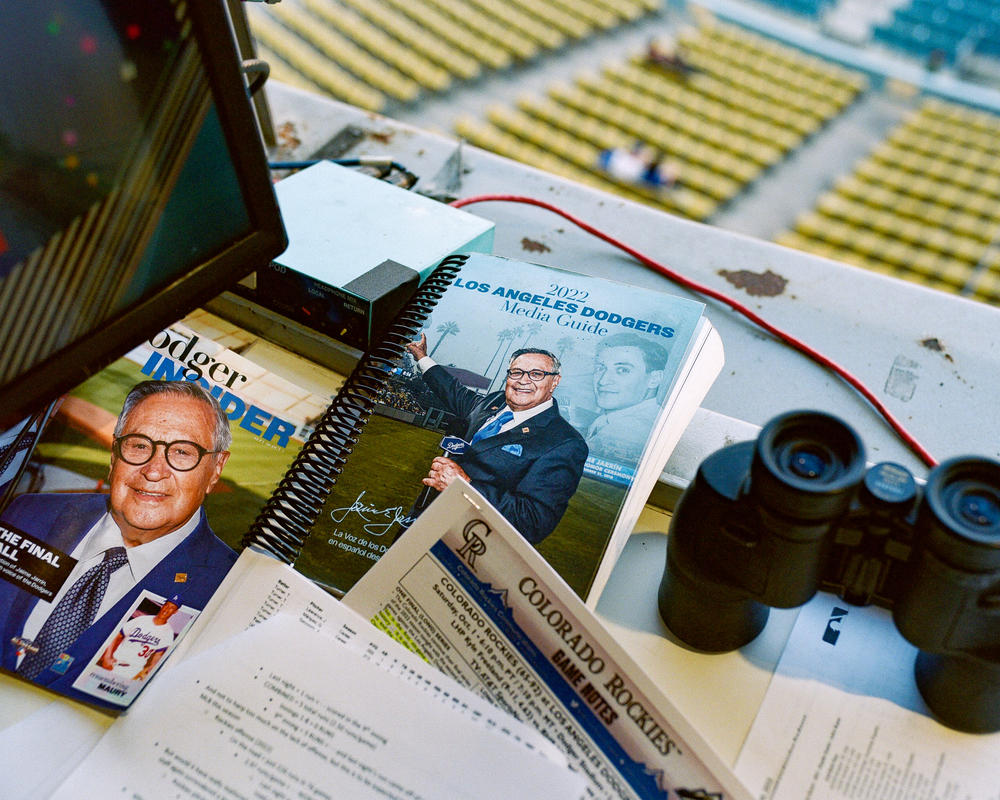

It's not as monotonous as I may have made it seem, because Jarrín, 86, is the Spanish-language radio play-by-play broadcaster for the Los Angeles Dodgers, and he's been at the mic for them since 1959.

This is his hallmark home run call: "Se va, se va — y despídale con un beso!"

In English, it translates to: "It's going, it's going — kiss it goodbye!"

Trust me, it sounds sooo much prettier to hear him say it in Spanish.

The thing is, he won't be saying it for much longer. That's because whenever the Dodgers finish their playoff run, Jarrín is going to call it a career. And what a career it's been.

'I never saw a baseball in my life'

Jarrín's time has served as a historical and generational bridge for Spanish-speaking baseball fans in the city of Los Angeles. He called the Dodgers first World Series win in L.A. in 1959, along with the next two they won in the '60s, the two they won in the '80s, all the way through to their most recent championship in 2020.

His voice, combined with his skill, earned him the highest honor a baseball broadcaster could ever hope for in 1998 when he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Looking back on Jarrín's career now, his relationship with Los Angeles baseball feels timeless — something that seemingly has always been there. But when he first started that part of his career, that wasn't exactly the case.

"I never saw a baseball in my life, a bat, or nothing, until I came to this country," Jarrín told me. The reason why is because Jarrín was born and raised in Ecuador — a place where soccer dominates. There, kids grew up wanting to play in the World Cup, not the World Series.

His first love was radio, a world introduced to him by his cousin Alfredo who was an up-and-coming radio announcer making a name for himself in Ecuador's capital city of Quito. Jarrín says Alfredo opened the door to a world that would one day become his life.

"He used to take me to see the shows on Saturday nights, and I fall in love with radio when I was 10 years old," Jarrín said. "Then, a couple of years later, he says, 'Jaime, I think you have a microphonic voice.'"

From there, Alfredo took that nascent 10-year-old "microphonic voice" and helped Jarrín develop it by making sure he did plenty of reading, but in a confident and conversational way.

"He put me in a corner of a room to read every day, about 30 minutes, in the newspaper El Commercio Quito. He said, 'I'm putting you in a corner because you will hear yourself the way that we hear you.' So, that was my first lesson: reading the newspaper, 30-minutes every single day."

All that reading paid off, because within just a few years, Jarrín started to resemble his cousin. When he was still a teenager, he had a two-hour show on Saturdays and Sundays and was beginning to make a name for himself in Ecuador as a rising radio star.

A bumpy move — and then a big break

OK, so you're Jaime Jarrín, it's the mid-1950s and you've already made some pretty big moves in the world of Ecuadorian radio. What's next?

Well, this is where Jarrín's story becomes something a lot more recognizable to many Americans. Just like countless people before and since, Jarrín went in search of a better life for himself and his family. The only question was where he'd find it.

He considered New York and Chicago, but eventually Los Angeles started to look more attractive to him. It was the post-World War II boom in which the country was suburbanizing, building out its interstate highway system, and California with its palm trees and sunny weather seemed like the perfect place to be.

Especially for an immigrant like Jarrín.

"I start reading about Southern California and I start reading about Los Angeles and how many Spanish-speaking people were here. So I said that's the place I have to go," Jarrín said.

Between 1940 and 1950, Los Angeles County's population grew more than 48% to more than four million people. And with that growth came opportunity. Just not the opportunity Jarrín was looking for — at least not at first.

"I took a job making metal fences in East Los Angeles," he said.

At the time, L.A.'s lone Spanish-radio station didn't have any open positions. But more than that, the people at the station took issue with the way Jarrín spoke Spanish. They felt that his Ecuadorian Spanish would sound strange to Southern California's large Mexican population.

Now, you might think, it was the 1950s and it was a different time. Well, 40 years later when I was starting my radio career in Los Angeles doing traffic reports in Spanish, I too was told my Ecuadorian Spanish would sound strange to Southern California's Mexican population. So, just as I was told to do, Jarrín worked on neutralizing his Ecuadorian accent.

"I went to study Spanish at the Cambias School Los Angeles," he said. "I was there 7 o'clock to 11 o'clock in the morning. I keep going until finally, they give me a job on weekends," he said.

Jarrín wound up becoming the news and sports director for KWKW. But then in 1957, the world of baseball was turned on its head. The Brooklyn Dodgers, the team where just a decade prior Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, were contemplating a move from New York. The Dodgers were trying to get a new ballpark to replace tiny Ebbets Field, but things didn't work out, and in 1958 they moved to Los Angeles.

William Beaton owned KWKW and when he secured the broadcast rights he made a decision that changed Jarrín's life forever.

"Mr. William Beaton called all the announcers to his office to let us know that they signed the contract to do the games in Spanish," Jarrín recalled. "And looking at me, said, 'I want you to be one of the two announcers.'"

That meant Jarrín, who was fluent in English and Spanish but only barely literate in the language of baseball, became part of the first crew ever to call Dodger baseball games in Spanish.

So, once again, just as he did when he learned to be a broadcaster in his teens, Jarrín educated himself by becoming a student of the game. He attended minor league games around Los Angeles, he got his hands on all the newspapers he could to keep up with the league, and he really immersed himself in America's pastime.

"I'd listen to every single broadcast on radio in 1958. So in 1959, I said, 'I'm ready.' So I started little bit, little bit — to one inning first, to two innings, to three innings."

Within a few years, Jarrín established himself as a standout announcer. It was also around this time when other teams started to realize how much money could be made by catering to Spanish-speaking audiences.

"When they saw the success of the Dodgers with Latinos, they started wondering, that's a great source of income also for the ballclub," Jarrín said. "What you have to do is hire a couple of announcers, hire a salesman, send him to the street, to sell Spanish broadcast, and it's a great, great way of making money."

Jarrín found himself pioneering what we might call today "diverse marketing", and a short while after that, he found himself at the center of a mania taking over the world of baseball: Fernandomania.

Late in the 1980 season, Fernando Valenzuela (who was born in Sonora, Mexico) was brought on to pitch for the Dodgers. The following year he won the National League Cy Young and Rookie of the Year award while helping the Dodgers win the World Series. But more than that, Jarrín says, he helped further open up the world of American baseball to Spanish speakers.

"He created so many new baseball fans — it was unbelievable. People didn't know baseball at all, so we had to teach them. They cared only about soccer and boxing and that was it," Jarrín said.

And the learning process did not stop there. In addition to broadcasting in Spanish, Jarrín worked as an interpreter for Valenzuela, helping him handle media appearances. Not only did this help further open up baseball to Spanish-speakers, it raised Jarrín's profile as well.

"Up to that day, I was very well known only in Southern California. Nobody knew about Jaime Jarrín in New York, Chicago, or San Luis (St. Louis). Then when I had to travel with Fernando and be with him in front of the media, they know about who Jaime Jarrín was."

An inspiration during a time of change

In the years Jarrín has been in the league, the impact and influence of Latinos in baseball has only grown. When he first started broadcasting in 1959, around 6.5% of all MLB players were Latino. When Valenzuela joined the Dodgers, that number grew to 11%. And on Opening Day 2022, more than a quarter of all MLB players were Latinos.

You can also see that growth in the stands too. I was only 11 years old when Fernando Valenzuela broke through, but I remember noticing a lot more Spanish speakers at Dodger games. They'd have transistor radios in their hands to listen to Jarrín's broadcast.

Alex Padilla was among them. He grew up in Los Angeles' San Fernando Valley and now serves as California's first Latino United States Senator. Padilla grew up bilingual but his parents only spoke Spanish. So in order to enjoy Dodger games as a family, they would all listen to Jarrín's voice narrate the action. Padilla says Jarrín was an inspiration.

"It was smooth. It was so descriptive," he told me. "It was literally, you can close your eyes and just listen to him and know exactly what was happening on the field because of how descriptive his voice was. But as a Latino, as a bilingual Latino, great to sort of be seen by his voice."

Jarrín's voice gave Padilla a sense of pride in his Latinidad and in his cultural identity that shaped the adult he later became. And it was also helpful that while Jarrín had a lot of ears listening to him, he was also aware there were a lot of eyes watching him.

"I think, whether it was intentional or not, he carried himself as a role model," Padilla said. "I think he knew he had that sort of on his shoulders, if you will, not just to be a good broadcaster in the booth, but, you know, being a symbol, an icon for so many Latinos throughout Southern California and beyond."

"He knew there was a responsibility that came with that, in terms of your contact at work and outside of work. It's something that I've tried to emulate in my own career."

As well as setting a positive example for Latinos to look up to, Padilla also appreciates how Jarrín looked out for the Latino community.

"In my conversations with him and his observations about life in Los Angeles and the Latino community broadly, it was clear that he was also listening to us and he had thoughtful conversations about advocacy for our community, justice for the Latino community," he said. "It was clear that he was watching as the population grew, as the population evolved, not just in the seats of Dodger Stadium, but throughout."

Today, after more than six decades in radio, Jarrín says his priorities have shifted. He's less focused on the day-to-day work and more focused on broader, loftier things, such as impact and legacy and with creating opportunities for a new generation through the Jaime and Blanca Jarrín Foundation, which he started with his late wife.

In many respects, Jarrín's resume speaks for itself.

He's in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, he's got his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and he's even received an Honorary Doctorate from Cal State University, Los Angeles. He's also in the Smithsonian Institute and the Museum of American History.

But he says the highest honor he's received doesn't come from any institute or committee or museum.

"What really fills my heart is when I am going to a supermarket or whatever, people approach me," he said. "They stop me and say, 'Mr. Jarrín, we just wanted to thank you very much, because thanks to you, I spend more time with my grandfather. Thanks to you, my father used to spend more time with me. So we just wanted to thank you for that.' And that really is the most appreciated compliment that I can receive."

If the Los Angeles Dodgers wind up winning the World Series or fall short, know that whenever they play their last game of 2022, it will also mark the end of a more than seven decade journey. One that started with reading the newspaper for 30 minutes a day in Quito, Ecuador when he was 10, to eventually becoming one of the greatest broadcasters of all time.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.