Section Branding

Header Content

Art and advertising collide in 'Objects of Desire'

Primary Content

Luscious, no? Really red lipsticks, five of them, in the hands of men in World Bank charcoal and pinstripe jackets. Glamourous, kind of sexy. But look a little longer. Notice the lipsticks are pointing at one another? Like daggers, or maybe red bullets. Cosmetic warfare. The two Italian artists of Toiletpaper (sorry, that's the name of their magazine) are not making an ad for Revlon. They're making art. The work takes the vocabulary of ads (bright color, shiny surfaces, slick lighting) and manipulates, repositions, rearranges it into fine art that can hang in a museum.

The LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art) show is called Objects of Desire: Photography and the Language of Advertising. Curator Rebecca Morse says the reconfiguration started in the 1970s, when "contemporary art photography had developed suffocating parameters." It had to be black and white, had to measure 8x10, "and anything else wasn't considered art." To break those barriers, they took real ads from magazines and billboards, re-photographed and manipulated them, and got them into galleries and museums. Why? "To get viewers to look at them more critically than you would if you were just flipping through Vogue."

But ... Spam? Enthroned on a bed of aspic? LACMA bought the picture (all the works in the Objects exhibition are from the museum's collection). Does it look more appetizing on a museum wall? Food is a theme in the show. Much of it is tough on your teeth — sugary. But not this one.

Plenty of grocery stores advertise their produce — lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers. But those in Elad Lassry's piece are polished like jewels, and have the uncanny ability to lean up against each other in impossible positions. They're very green. And it's not easy being green and stand on end, gleaming.

Actual jewels appear in Roe Ethridge's Celine Bracelet for "Gentlewoman," but you don't see them right away.

The grapes are fake, the berries too. The pear is marble. The cheap cigarette lighter, however, is real. And it's a real ad! But it's odd. The pale amber-colored bracelet snaking down on the right is what's being sold. Curator Rebecca Morse points out that in the ad Ethridge uses the stylings of fashion and product photography, "studio lighting, figure isolation, enhanced color," and then adds "little disruptions that make the image his own." In the catalogue Etheridge says, "the best images are the ones where something goes wrong a little bit."

It is odd. An indictment, perhaps, of the commercialism of society? Morse thinks it speaks of spending on stuff you don't really need. Commercial ads hit our insecurities — if you buy this product it can solve that problem (pale lashes, rumbling stomach). "The ads are colorful and commanding. But when you really look, fine art photographs are showing us overconsumption, the thought that we can satisfy our desires with products," Morse says.

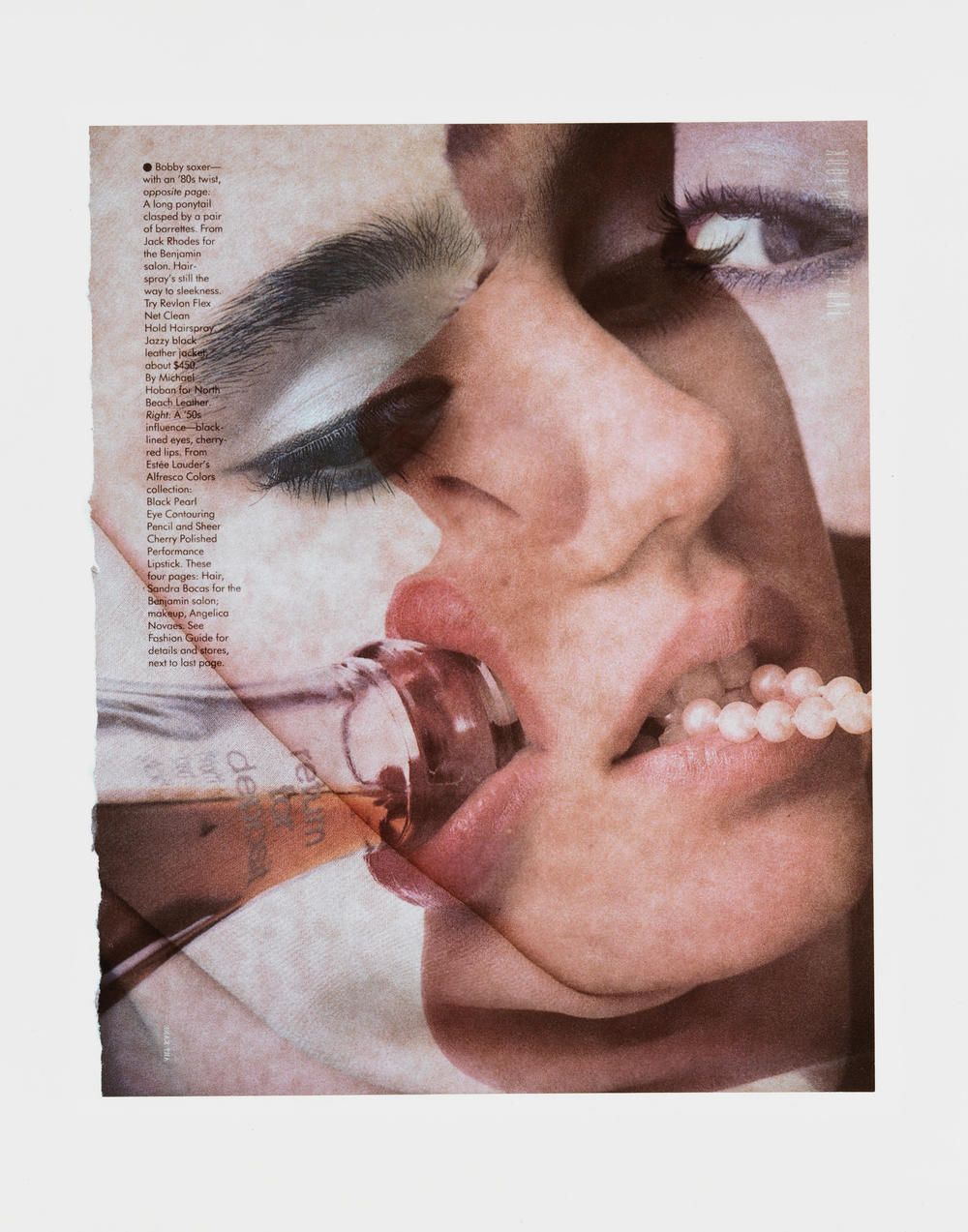

While I see Picasso, Morse sees something unnerving, even sad in this picture. It's an example, she says, of "how women are used to sell products." If Heinecken showed just a single face — the profile, drinking soda — "it would be OK." But the two black and white eyes, and the colored three-quarter face with pearls, propels the piece into mystery and desire. "It makes you stop and think, 'What are we doing with our space and our time and money, and the things we're being conditioned to covet?' " Morse asks.

To me, the work is also about truth and reality. Advertising's job is to enhance and manipulate both. You test whether pearls are real by rubbing them along the rim of your top teeth (do not try this while eating caramel). If they feel a bit gritty, they're real pearls. If not, well ... think Spam could pass that test?

Art Where You're At is an informal series showcasing online offerings at museums you may not be able to visit.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.