Section Branding

Header Content

All the president's men: Why succession may pose a problem for Xi Jinping and China

Primary Content

BEIJING — Chinese leader Xi Jinping is now unrivaled.

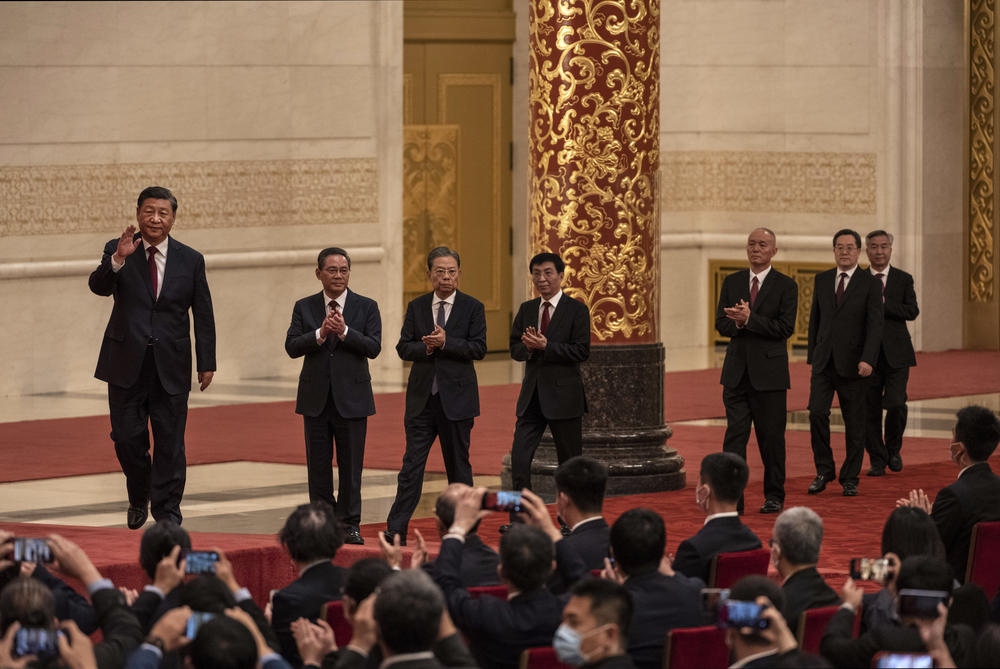

At a Communist Party congress that ended over the weekend he extended his rule beyond the standard 10 years, sidelined opponents and stacked the leadership with allies.

What the 69-year-old strongman did not do was anoint a successor.

Analysts say that's likely an effort to retain maximum power in order to see through an ambitious policy agenda — but it raises the political stakes, and puts China's hard-won stability at risk.

"History shows very clearly that the problem of succession creates political instability," said Jorgen Moller, an expert in succession at Aarhus University in Denmark.

Most attempts flopped

Most attempts at leader succession in China since the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 have flopped.

Founder Mao Zedong's first anointed successor, Liu Shaoqi, was eventually purged during the Cultural Revolution and died in prison in 1969. His next choice, Defense Minister Lin Biao, perished in a mysterious plane crash as he tried to flee the country in 1971, possibly after attempting a coup.

When Mao died five years later, his last pick, Hua Guofeng, took over. Hua managed to hold onto power for a few years, but was eventually sidelined by Deng Xiaoping.

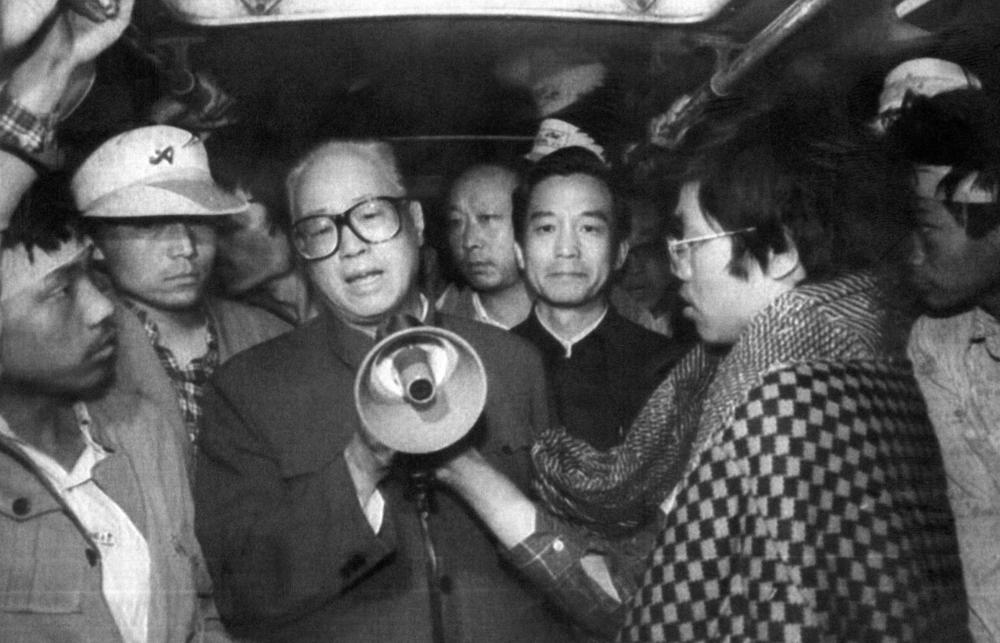

Deng, too, had problems with succession. Reform-minded party chief Hu Yaobang was ousted by hard-liners. Zhao Ziyang, who followed him, was ejected and spent his final years under house arrest for siding with the protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

But then things settled down.

Deng managed to get buy-in from other party power brokers for an unwritten system that set somewhat flexible retirement ages, capped leaders to 10 years at the helm, and promoted and groomed would-be successors several years out.

Benjamin Kang Lim, a journalist in Beijing with Singapore's Straits Times who has covered every party congress since 1997, says the first big test was the 16th Party Congress — and the party passed.

"Back in 2002, it was the first orderly transfer of power since 1949," he said. "There was a logic to it, right? There was the retirement rules, seniority."

To be sure, when Jiang Zemin handed the reins of the party to Hu Jintao that year, he held onto his role as chairman of the Central Military Commission, effectively commander-in-chief — an example of the flexibility of the purported rules on succession.

Nevertheless, two years later, the full transition was completed when Jiang gave up the military post.

Bucking historical trends

According to Moller, China was bucking historical trends. He says authoritarian regimes have typically stumbled with succession because institutions are unable to constrain rulers; laws are seen to exist to serve the regime.

"The Chinese case was then used as an example in the literature on authoritarian systems that sometimes you can actually have institutions that seem to do the job," he said.

Although Deng's rules were often bent, Xi Jinping seems to have jettisoned them altogether.

Xi cashiered two men who a few years ago were promoted into positions that analysts said made them likely successors, finally pushing one to the side at the party congress that just ended. He abolished the norm on term limits. And he's concentrated and personalized power to a degree unseen since the Mao era.

"And so when Xi Jinping at some point has to retire, there's no clear model for how that will be done," said Moller.

That's potentially dangerous for the world's second-biggest economy, and a budding superpower with a growing nuclear arsenal. If elites don't know what to expect after Xi, analysts say, they risk losing out when the leader dies or moves on — and it raises the stakes.

"In historical terms, that could be a very big problem," Moller said. "It could cost elites their land. It might even cost them their lives." Or lead to war.

The new line-up of the seven most powerful men comes at a precarious time for Xi and his country. China's economy is set for its slowest growth in decades, tensions with the U.S. are high and escalatory rhetoric over Taiwan has become shrill.

"He's not going anywhere"

Rana Mitter, a historian at the University of Oxford, says none of that is lost on Xi.

"Xi Jinping wants to make it very clear that he's not going anywhere and the people shouldn't spend time speculating about who comes next," Mitter said.

Xi has rejected collective leadership and espoused "the idea that he personally is very much associated with the next phase of development," he said.

At the party congress, Xi's ruling ideology and policy priorities won full-throated support. Mitter says Xi has consolidated power and doesn't want it diluted while pursuing those goals.

Benjamin Kang Lim, the journalist, says he expects that eventually Xi will put in place a new system for succession. Just not yet.

"Political succession, of course, is important," Lim said. "But I think it takes a backseat to where this leader or future leaders will take this country."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.