Caption

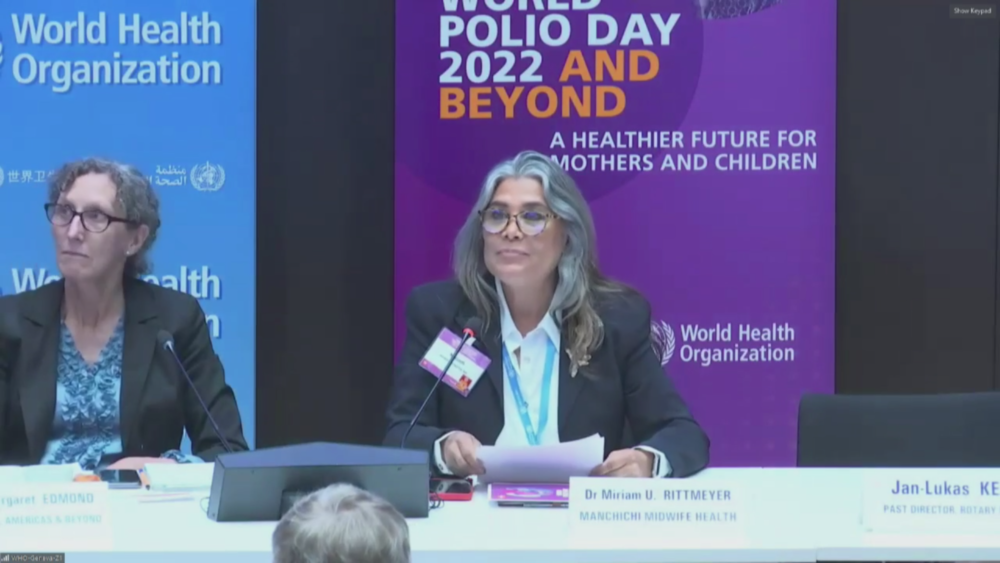

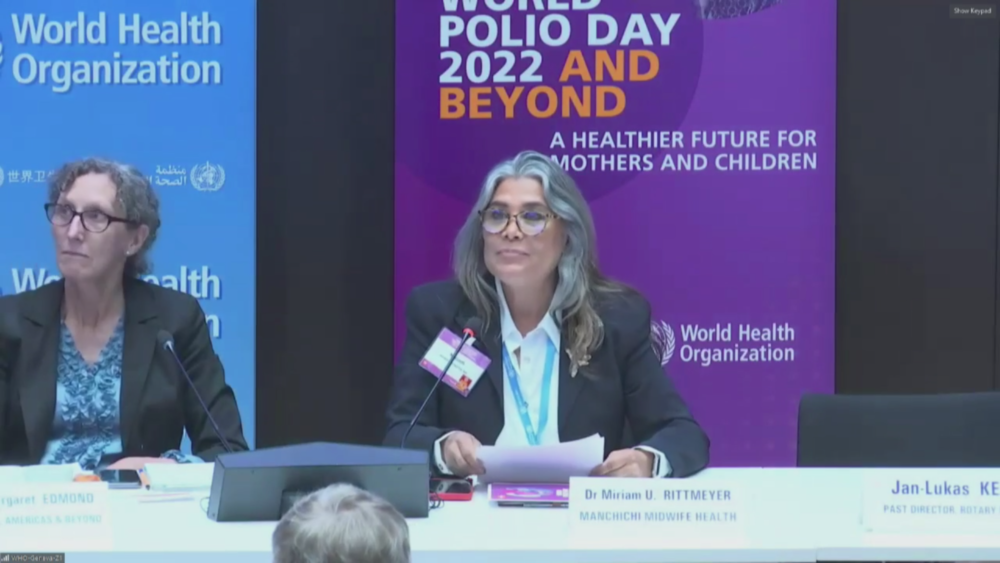

Dr. Miriam Rittmeyer speaks at the “World Polio Day 2022 and Beyond” summit in Geneva, Switzerland.

Credit: World Health Organization

LISTEN: Dr. Miriam Rittmeyer of Savannah was invited to the WHO's headquarters in Switzerland to present on her nonprofit's efforts to combat maternal mortality in Central America. GPB's Benjamin Payne reports.

Dr. Miriam Rittmeyer speaks at the “World Polio Day 2022 and Beyond” summit in Geneva, Switzerland.

A Savannah-based expert on maternal health addressed the World Health Organization in Switzerland on Saturday, sharing insights from a midwife education program that she helped develop in her native Guatemala.

Dr. Miriam Rittmeyer, who leads the international nonprofit Phalarope, presented at the “World Polio Day 2022 and Beyond” symposium, a two-day event in Geneva hosted by the WHO and Rotary International.

Rittmeyer spoke about Phalarope's Manchichi Program, which provides medical training to indigenous midwives in Guatemala and Panama in an effort to reduce pregnancy-related deaths in rural communities.

“We invest directly in training the local people, while acknowledging the previous work these midwives have done for generations,” Rittmeyer said at the summit.

Through the 12-month training, Rittmeyer said, midwives learn how to operate medical equipment and conduct prenatal care visits and physical exams, which can help them identify and refer high-risk pregnancies to doctors for treatment.

In addition, midwives are taught how to educate mothers themselves on unhealthy behaviors to avoid, such as alcohol consumption and smoking.

“We also teach these midwives how to assess fetal growth and position, as well as proper labor and delivery practices, which includes instrument disinfection,” Rittmeyer said. “Finally, we teach the midwives to [identify] signs of infection or conditions in both the infant and the mother during the postpartum period.”

It's not just the curriculum itself that has helped the Manchichi program expand to several indigenous communities in Panama — where it's being evaluated by the country's health ministry as a pilot program for all of Panama — but also the way in which that material has been taught.

“A key feature of the program is our culturally sensitive approach that is adapted to the local culture and language,” Rittmeyer said. “This increases patient adherence to treatment and the overall acceptance of the program.”

This culturally sensitive approach means respecting and incorporating long-held indigenous customs; for example, Rittmeyer said, many communities practice a tradition in which, after a mother gives birth, the placenta is burned to ashes and spread across the soil as a symbolic expression of fertility.

“As a fellow Central American myself, I appreciate the project's nature to be as inclusive as possible for our indigenous populations and to be culturally sensitive,” said summit moderator Dr. Nyreese Castro-Espadas after Rittmeyer's presentation. “It's something that is lacking quite a bit in our traditional health care system.”

By raising the standard of maternal health care among the most vulnerable of women, Rittmeyer told GPB News that she hopes her organization's work can inspire similar efforts elsewhere, including in Georgia — which ranks among the highest states for pregnancy-related deaths.

“We need to think about these programs as very important interventions,” Rittmeyer said. “In the U.S., there is access up to a level for certain women. But still, there is a lot of things to be done.”