Section Branding

Header Content

'It chips away at you': Misty Copeland on the whiteness of ballet

Primary Content

At first, Misty Copeland thought the pain she was experiencing was shin splits. It was 2012, and, after 12 years with the American Ballet Theatre, Copeland, one of the few Black dancers in the company, had finally landed her first leading role in a classical work.

"I knew how critical this moment was for my career," she says. "If I had gone to the artistic staff or the physical therapists and said, 'I'm in a lot of pain,' they would have removed me from the rehearsals. And I would not have been able to perform. And I knew that had that happened, I wouldn't be given the opportunity again."

So she pushed on, dancing the principal role in The Firebird, despite the fact that the pain was becoming increasingly severe. Finally, toward the end of the company's season, Copeland was diagnosed with six stress fractures in her tibia — three of which were classified as "dreaded black line" fractures, meaning that there were almost full breaks through the bone.

When the first surgeon warned her that she might never dance again, Copeland was devastated. "It was just like my whole world came crashing down," she says. "I felt mostly like I was letting down the Black community."

As a Black woman, Copeland had heard for years that her skin color, her body and her hair didn't conform to what ballerinas were supposed to look like. After finally opening a door in the ballet world to other dancers who looked like her, she didn't want that door to slam shut because of an injury.

"I must have seen seven or eight surgeons before I found the one that said, 'I see this injury in football players and basketball players that I operate on all the time and I can help you,'" she says. "And I said, 'Let's go.' "

Copeland wound up having surgery to insert a steel plate into her tibia. Eight months later, she was on stage again. She was still in pain, but it was bearable. In 2015, she became the first Black woman to become a principal dancer with the American Ballet Theater.

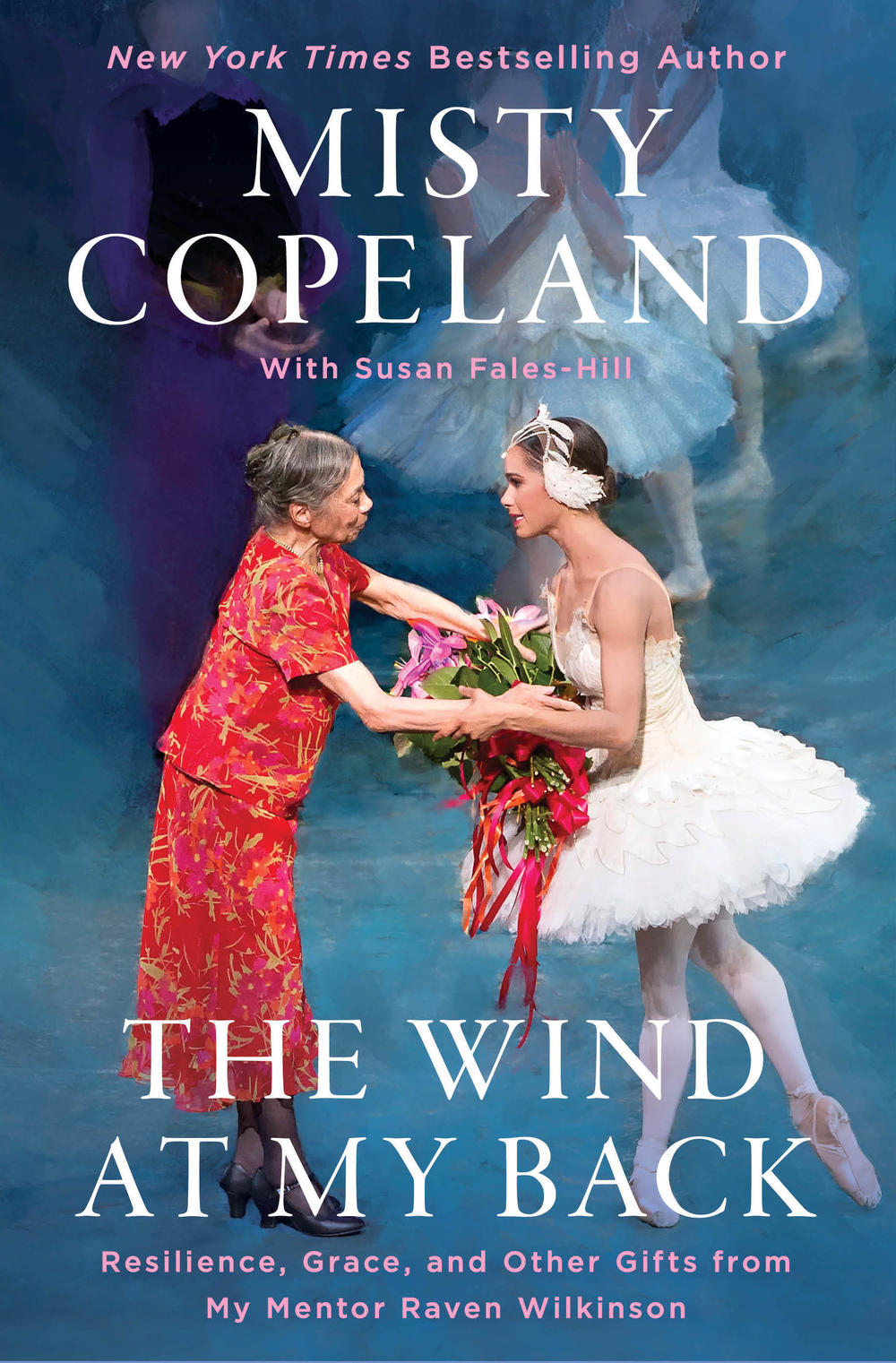

In her new memoir, The Wind at My Back: Resilience, Grace, and Other Gifts from My Mentor, Raven Wilkinson, Copeland chronicles the barriers she had to overcome to become a star in the ballet world. And she writes about her mentor, Raven Wilkinson, who, in 1955, became the first Black ballerina to receive a contract with a major ballet company, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

Back then, segregation was legally mandated in much of the South, and Wilkinson was not allowed to stay with the rest of the company in hotels or eat with them in restaurants. Ku Klux Klan members once stormed the stage of one of the company's rehearsals, looking for her. Wilkinson eventually quit the company and continued her career outside of America with the Dutch National Ballet. Copeland credits Wilkinson with helping her bridge the gap between her on- and offstage lives.

"All that she had experienced and gone through and learned throughout the course of her life, she channeled into her performances," Copeland says. "That was something that I hadn't quite done before I met her — was connecting the person I was trying to become off stage to the person I was on stage. Being a representation for young Black and brown people on the stage. Being comfortable in my skin and having a voice ... she kind of showed me that I could be all of those things off- stage as well."

Interview highlights

On experiencing homelessness as a kid and finding refuge in ballet

We were constantly moving [in with] people that I didn't know that were friends of my mom's. We were staying on their couches. It was literally from week to week, month to month that we were moving between people's homes or between motels. It was really difficult to be in school. I felt that I couldn't get close to anyone because I was so embarrassed about my home situation. I didn't want anyone to know what was going on, whether it was the relationships my mom was in and the abuse that was happening in the household. I just kept everyone at a distance because I didn't want them to know. And it was really stressful. It was really stressful to kind of keep up this façade of happiness.

It wasn't until ballet came into my life that I started to feel that I could be a person, a person in the world, like I could express myself. It was like I'd gone 13 years of my life without truly expressing what was inside of me or feeling comfortable in my skin. And it was ballet. And it was being in the studio, which felt so sacred. It felt so protective. And the same with the stage. I know it's like the opposite of what people would think of performing. You're up there and you're so exposed and naked — and I felt the opposite. I felt like I finally found this place of comfort for the first time in my life.

On how living with her dance teacher Cindy Bradley changed her life

I was severely underdeveloped in every way, physically, mentally, emotionally. ... When I lived at Cindy's house, I started to develop physically because I was getting nutritious food. I was having conversations with Cindy and with her husband, conversations that I'd never experienced my entire life. Being one of six children, it's hard for my mom, who's working several jobs and just trying to survive, to keep us off the street, to have these intimate conversations with each one of us. I also just don't think it was really in her nature because of the way she was raised as well, this lack of communication. And I was forced to do that at Cindy's house and I grew and developed immensely in the three years that I lived with them.

It also was the first time I was in a stable environment that wasn't chaotic, that I could hear myself think. It was peaceful. And I could really just focus on the training, which is why I moved in with them, was to be able to catch up on all the training that I missed out on by starting at 13 years old, which is late in ballet standards, because I would eventually go on to join American Ballet Theater with only four years of training under my belt.

On being told her body was "wrong" for ballet

What's interesting is when I started ballet at 13 years old, I was told I had everything that it took to be a ballet dancer, physically, artistically. So that's why there's kind of this interesting dichotomy when I think about Black women specifically in ballet and the language that's being used in telling us that we are wrong for ballet. Again, I had the ideal body when I joined American Ballet Theater. Of course, I went through puberty — and like a lot of dancers who become professionals between the ages of 16 and 18 ... my body did change. But once I became a professional, that's when people started to really see me as a Black woman in a company where there weren't any. And that's when the language started to change around me fitting in.

Still, to this day, I will read things that [say] I don't belong because my breasts are too large, my muscles are too big, I'm too short. But these are all excuses because there are so many dancers who are not of color, who have similar body types to me that are shorter, that have larger breasts and bigger muscles. So throughout the course of my professional career, it's really been about me understanding the language that's being used and having conversations about that because that's been what's turned so many Black women away from ballet is because they're told those things.

On being told she should do modern dance instead

When you think about these cultural art forms and dances, people often see Black Americans and they think, "Well, you should be doing your cultural dance," whatever that is ... whereas white Americans aren't told they can't do this European art form. So that's just kind of been this pattern with Black and brown dancers is that they feel that we should be doing African dance or with our bare feet, modern dance — and that shouldn't be the case. I think everyone should have an opportunity to be a part of this art form and experience it. And it makes it so much more full and rich and layered to see different people with different perspectives and different life experiences and different cultural backgrounds all approaching the same craft and art form you dance.

On how whiteness has been traditionally considered to be intrinsic to classical ballet

The norm is that everyone wears pink tights and that's representative of white skin. So it was something I was aware of when I was 19 and came into ABT that I would have to wear pink tights ... and then have to go on stage and attempt to make my skin look like the other dancers. It chips away at you. The more that I look around and not see people who look like me, not see other women who look like me, and I'm painting my skin over and over, it was something I started to talk about. ... And eventually, I don't know, maybe seven, eight years later, I would have that conversation with the wardrobe department, with hair and makeup and kind of debate what the sole purpose of this tradition is. ... If it's just to make us look otherworldly, then why can't I have brown powder to powder my skin to take that shine away? Why am I changing the color? And I did it as a principal dancer the last time I performed the role of Swan Lake, I did that and in other roles where I was told to paint my skin white. So I did push back. But we have a long way to go, still.

On the pressure that came with being the first Black principal ballerina with ABT

When I was making these debuts in big, leading roles, for most dancers, you'll make your debut on a Wednesday matinee. And some people will come and there probably won't be a critic there at all to critique your show or talk about it. And I had the exact opposite experience. Every time I was making a debut in a role, The New York Times was there. There were blogs and people writing, "Will Misty succeed? And if she doesn't, what does that mean for her career? What does that mean for the African American dance community?" So there was a lot of added pressure outside of just being an elite athlete at American Ballet Theatre and all that it takes to perform these roles, which is extremely pressure-filled and difficult.

On performing while in terrible pain and not showing it

I think any ballet dancer, any ballerina would tell you that it's a part of the training. We are athletes, but we are also performers and we're also artists. So we're not just training in the ballet technique, but our goal is to tell the story, to make it look effortless, never to show any weakness or pain. It's just a part of what we have to do when we go on stage, it's a switch that turns on where you almost don't even feel the pain. There's so much adrenaline rushing through you and you enter into this fantastical world of whatever ballet you're performing, whatever character you're portraying — and it's like you're no longer human. And that was the case even in that last performance [of The Firebird] when I could barely walk when I was off stage, but I'd get on stage and somehow could muster up all the energy and courage to keep jumping and performing.

On 'going into performance mode' while giving birth

People think I'm so crazy when I talk and I write about it. But I really enjoyed being pregnant. I enjoyed labor. I enjoyed all of it. There's something about, I think, being an athlete and being used to the physical pressures. ... Something clicked in me where it was like, "This is so familiar." I know what it takes to get my mind mentally prepared and focused for a difficult physical feat — and that's how I felt giving birth to my son. ... The actual labor was 15 hours, but the delivery ... was quick. My doctor said to me right when I started pushing, she said, "This could take three to four hours." And I was like, what? That was never mentioned. And I said, "This is not going to take three to four hours! I'm not going to let that happen!" And I pushed Jackson out in 28 minutes.

Lauren Krenzel and Seth Kelley produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.

Copyright 2022 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.