Section Branding

Header Content

Video games are tough on you because they love you

Primary Content

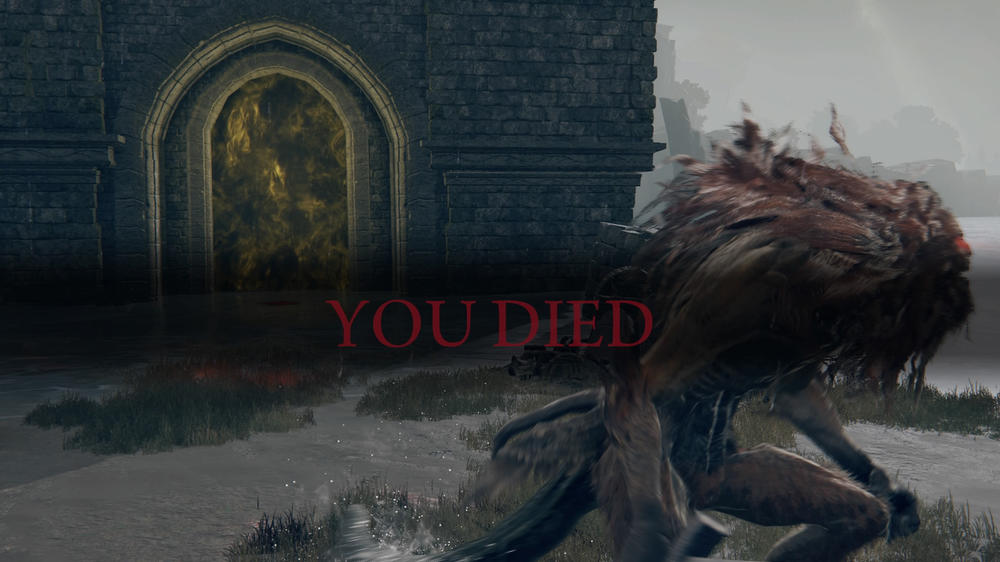

"Game Over." "You Died." "Wasted." These phrases are rites of passage, a chiding to video game players ill-equipped for the task ahead. Whether you're controlling Leon Kennedy's ragdoll body spinning from an exploding tripwire in Resident Evil 4 or losing a fight to a cheap low sweep in Super Street Fighter 4, dying sucks.

But that doesn't mean you do.

It's easy to attribute a loss — or several losses in a row — to being "trash" at a given video game. The genesis of the "git gud" mantra hinges on the premise that you're just a bad gamer.

But that couldn't be further from the truth. Failure in games has always been a stepping stone to discovering the kind of player you are.

Growing older and wiser

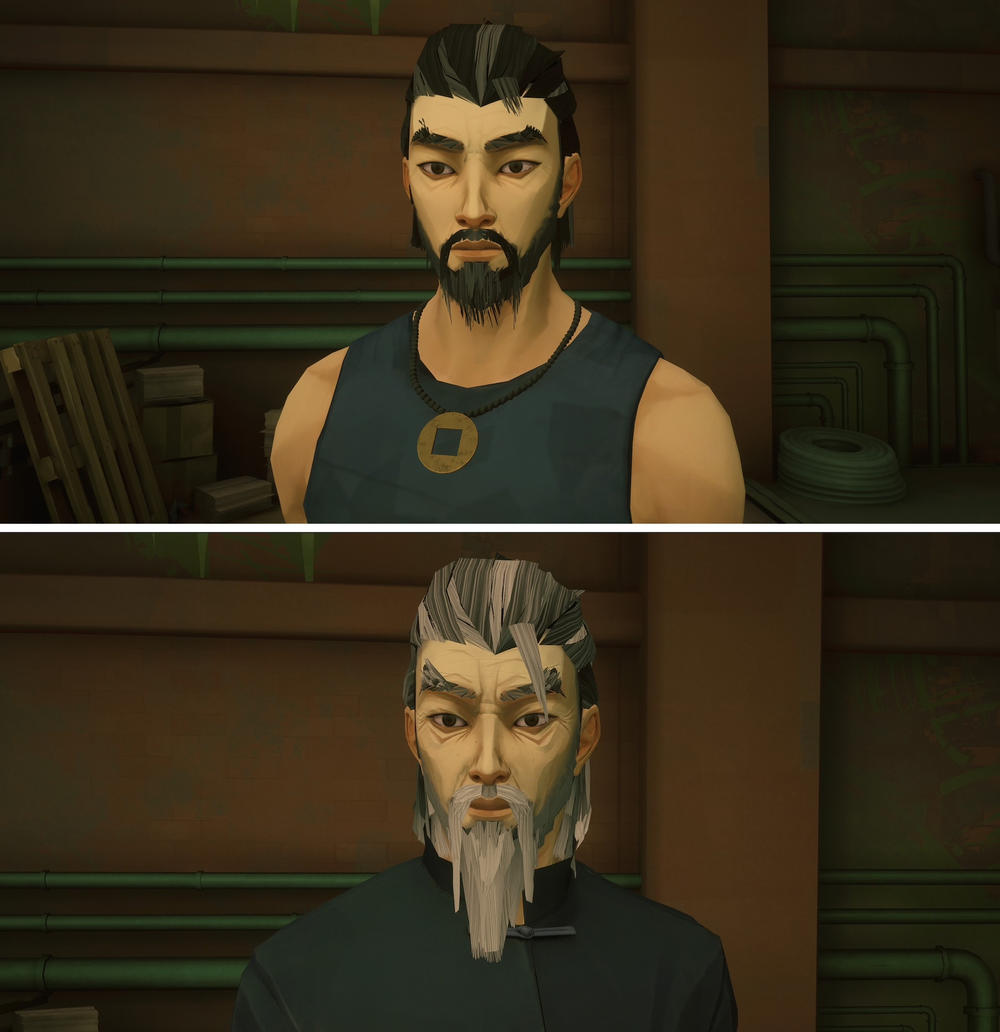

In February, French studio Sloclap released Sifu, an action beat 'em up title that tested the mettle of players looking for a challenge. The difficulty was so intense that it literally ages the game's protagonist. It throws legions of goons at you, and upon dying, you get upgrades as your character gains wrinkles and gray hairs.

The result was a grueling, rewarding, wholly-maddening experience that reignited the polarizing conversation of what it meant to be skillful in games. Were you good at Sifu because you played without dying or taking damage? Maybe you were better because you stuck to Master difficulty when a patch was later released to flatten the difficulty curve?

Dying in Sifu doesn't mean you're playing the game wrong — it's an essential feature of the game that leads to greater potential for your character, while building a unique narrative of aging and revenge. And it's not the only big title this year to pit players against their own wits and to reward "failing forward."

Gathering around the Ring

FromSoftware's Elden Ring was the latest in a portfolio of grim commercial hits, and when it also released in February 2022, its popularity surprised even its publisher.

Spiritual predecessor Dark Souls epitomizes the toll death takes on a player — that series' macabre atmosphere and Lovecraftian horrors have cultivated a space where community has thrived. Elden Ring is no different, as it utilizes the same cooperative features to help players lean on each other, in addition to plentiful guides and walkthroughs posted online.

Despite the availability of these resources, some fans assert that if you use these tools to beat the absurdly challenging bosses in Elden Ring, you never really played it as intended. Community members on Reddit and other message boards have called out "gatekeepers" who shame players for summoning allies — a co-op feature present in FromSoftware titles since 2009's Demon's Souls.

Dying in Elden Ring or other Souls games doesn't mean you suck either. Instead, failure pushes you towards channels of communication and cooperation that could otherwise be missed. It fosters a space for new and veteran players to exchange ideas and to create some silly content.

It also taught me that wandering can be a good thing — I've died far too many times to count to Elden Ring's hulking ogres, knights, and bears. I initially hated its obtuse systems. Yet through the support network built around it, I learned ways to cope with the game's overwhelming challenges.

Dedicated fans are eager to prop up signposts when players grow understandably frustrated at the new and lethal things lurking in the Lands Between. It's a testament to the universal struggle we share in recovering from a death screen.

Can't catch 'em all

Death and dying aren't exclusive to the dark and dreary. Even franchises like Pokémon have courted challenges meant to fluster the most accomplished trainers.

Fans have long designed "Nuzlockes" as ways to ramp up the difficulty of these otherwise tame games. A "Nuzlocke" run involves self-imposed rules a player must keep while navigating the Pokémon game of their choice.

The phenomenon is not unique to these titles but has thrived because of community efforts to share as much information as possible to beat a given "Nuzlocke." These arbitrary rules may force you to only catch the first Pokémon you encounter on any route, or could limit how many Poké Balls you could carry or purchase.

Pokémon Emerald Kaizo is widely regarded as one of the most difficult "Nuzlockes" to complete because of its unforgiving rules, with enemy variety that trumps the base game's original design. There is also a gentler route for those wanting to meander a bit, like I did with a custom randomizer for Leaf Green that changes every Pokémon you encounter, including starters.

Failing a "Nuzlocke," aging in Sifu, or even summoning in Elden Ring are not indicators of a bad player. Conversely, they're challenges that build community and self-growth — they force you to learn how to be better at the thing you love playing.

If failure is the stuff of life, then it should count doubly in the digital space, where stakes are far more forgiving. The next time you hit 'play again,' remember what Michael Jordan, one of earth's mightiest athletes, said in that classic Nike commercial: "I've failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed."

Jamal Michel is a freelance writer whose work focuses on video game culture, entertainment and the stories in between them. He is currently a member of the Life Kit and It's Been a Minute teams.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content