Section Branding

Header Content

Europe fears its industries will jet to the U.S. as energy costs force plant closures

Primary Content

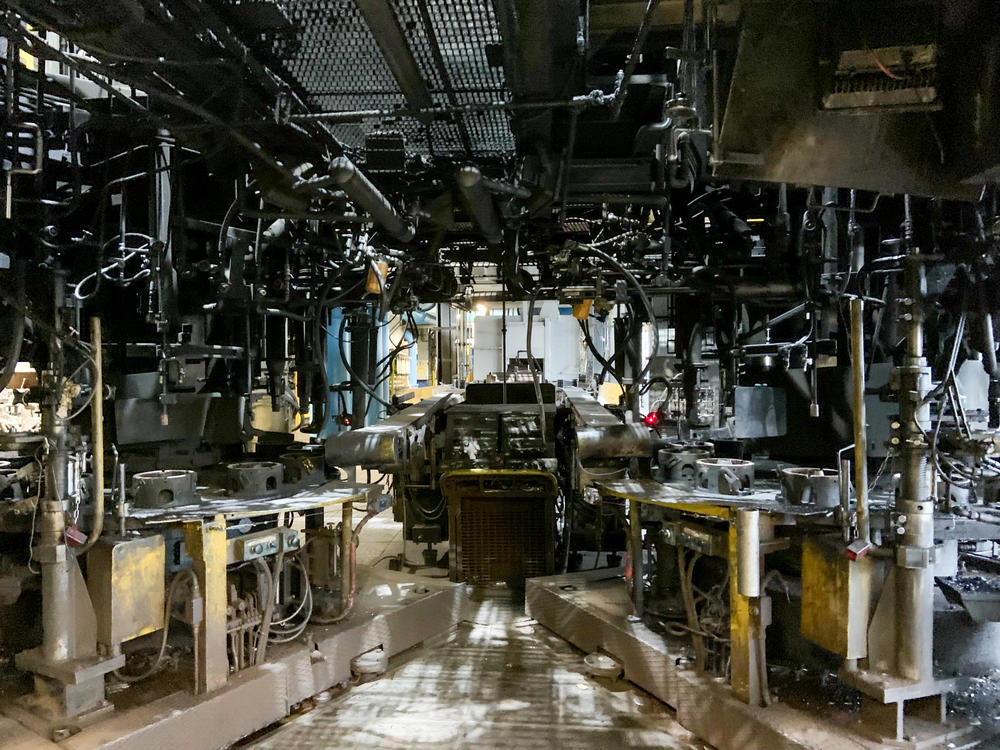

ORLÉANS, France — The assembly line at the Duralex glassware factory sits idle, its massive industrial equipment lies dark and still.

On a normal day, 250 employees work around the clock producing 200,000 sturdy glasses and bowls.

But earlier this month, the plant in Orléans suspended operations because production costs had spiked after Russia throttled its natural gas exports to Europe. That put many of its workers on furlough.

Skyrocketing energy prices could shatter the image of this iconic glassmaker — and alter the industrial landscape of Europe, as European policymakers and analysts increasingly worry that businesses could pack up and leave for the United States.

Guillaume Bourbon, a forecast manager for Duralex, says the company had to halt production when natural gas soared to 40% of operating costs from as low as 4% a year ago.

"It's crazy for us," he says on a tour of the plant. "We can't pay that much for energy. It's simply not possible."

Duralex, which exports 80% of its products, has had many highs and lows since its founding in 1945, says Bourbon. But he never imagined this.

He says the company negotiated a much lower, three-year energy contract starting next April 1 and will resume operating. But the volatility makes projecting business costs beyond that impossible.

Companies across Europe are going into sleep mode. Gas-heavy fertilizer makers have all but halted production. Steelmaker ArcelorMittal has temporarily shuttered mills in France, Spain, Germany and Poland.

None of this is helped by America's recently passed Inflation Reduction Act. It provides $369 billion in spending that includes subsidies to support companies investing in renewable energy. The incentives, combined with cheaper energy prices in the U.S., have raised fears of an exodus of European manufacturers to America.

"My concern as a European citizen is that these industries will be closed and will not start again," says François-Régis Mouton, regional director for Europe at the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers.

Europe has focused on climate

Mouton blames more than the war in Ukraine and Russia's decision to effectively slow its gas exports to a trickle. He says the European Union's policymakers should have tempered their ambitions for fighting climate change and considered efforts toward Europe's energy independence.

"They kept saying 'fossil gas, we have to kill fossil gas.' OK, we've killed it but how do we survive?" he says. "Instead of doing that they could have said it would be better to produce it in Europe and not be dependent on Russia. As a consequence of this, domestic energy production is declining a lot in Europe. Because we don't invest."

The EU dismissed fossil fuels in its effort to reach carbon neutrality by 2050, says Thierry Bros, a specialist in global energy at Sciences Po university in Paris.

"We've been saying to this [fossil fuel] industry that it's passé, that we don't need it," he says. "Well at the end of the day, if people want to heat themselves, if you want to cook, if industry needs to continue to produce, you need fossil fuels."

Now coal is back

And European leaders are aware of the serious energy needs to make it through winter. To fill the void from Russia's gas cuts, some countries are once again turning to coal.

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, Germany had committed to phasing out coal by the end of the decade. But instead of closing several coal-fired power plants by the end of this year, 20 are being resurrected — or extended past their closing dates — to ensure the country has enough energy to get through the winter.

European countries are also searching for gas for the coming winter. Much of the continent's current needs will be met by liquefied natural gas (LNG) imported from the United States.

But it won't be enough, says Bros.

Companies could leave for the U.S.

"Quite a few of these industries will never reopen in Europe," Bros says. "They're never going to get enough energy anyway so why on Earth would you use gas in Europe if it's coming from the U.S.? You're much better off putting your chemical company in the U.S."

There is increasing talk of a coming deindustrialization of Europe, bringing unemployment, a change of lifestyle and possibly social unrest.

This is exactly what Russian President Vladimir Putin wanted, says Bros. "He started two wars," he says. "One in Ukraine, and one against the EU using gas as a weapon."

Experts say European companies that shutter could move operations to the U.S., where energy is plentiful and much cheaper.

"Europe is faced with the flight of its industry, jobs and capital towards the U.S," French economist and historian Nicolas Baverez wrote recently in the magazine Le Point. He estimates it will take several years to compensate for Russian gas, and during this period energy will be rationed and expensive in Europe.

Fabrice Le Saché, a spokesperson for France's largest business association, MEDEF, calls the potential to lose businesses to the U.S. "a disaster for our economy."

"It's not a winning situation when you have your closest ally becoming very weak," he says. "It is not in U.S. interest to see our industry collapse."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.