Section Branding

Header Content

The unplanned, unstoppable career of composer Tania León

Primary Content

In the spring of 1967, Tania León won the lottery. Her reward wasn't any cash prize — instead, the 24-year-old budding pianist boarded an airplane just east of her native Havana, bound for Miami. León was one of an estimated 300,000 Cubans who left as refugees on the so-called "Freedom Flights," a program that ran from 1965 to 1973, organized by the U.S. and Cuban governments in a rare cooperative effort.

Although she came from a poor family, with a mother who couldn't read or write, León had rich dreams — as well as the support of a few well-wishers in her community who invested in her talent, including the gift of a piano. From the U.S., a mere stepping stone in her grand plan, she hoped to travel to Paris, where she would continue her studies and launch a career as a concert pianist. But her dream was deferred: As a refugee from Cuba, she learned she was required to stay in the U.S. for five years. She couldn't go to France; she couldn't even return home.

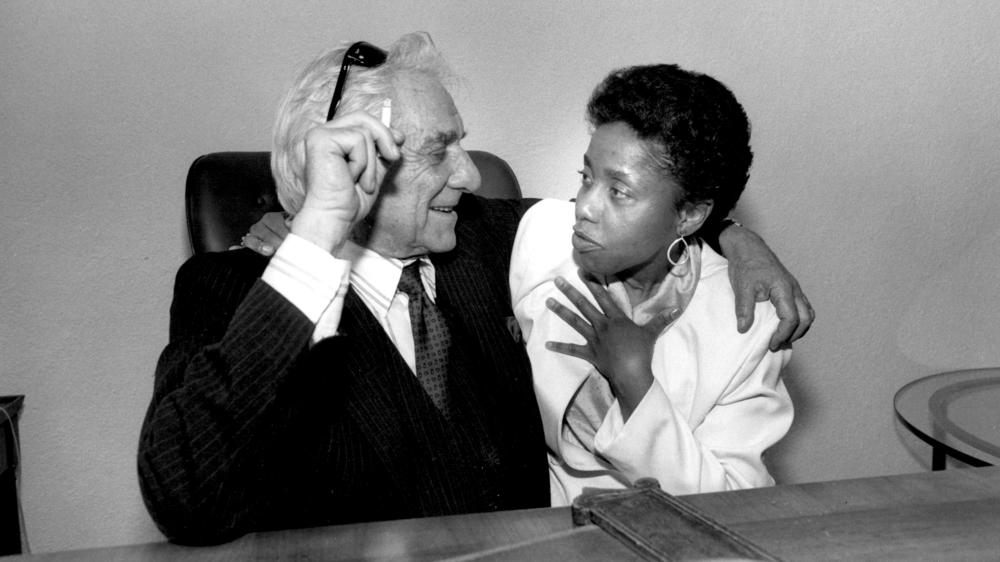

León quickly made her way to New York, where she met the dancer and choreographer Arthur Mitchell, who was busy with a dream of his own. After hearing her play, Mitchell asked León to help him establish the Dance Theatre of Harlem, and encouraged her to compose music for the company. The writing of that first ballet came so instinctively to León that she changed her major at NYU from piano to composition. She has followed it with six more ballets, an opera and a broad range of instrumental and vocal music.

León says she never planned to become a composer, much less one who earned a Pulitzer Prize. She won the award in 2021 for Stride, her orchestral work inspired by Susan B. Anthony's activism and premiered by the New York Philharmonic. She also never thought she'd be a conductor, but a little nudge from composer Gian Carlo Menotti and studies with Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa proved that she possessed that skill within her too. And through her 35 years as an educator at the City University of New York and the founding of Composers Now, a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting and celebrating living composers, she's found ways to reinvest those skills into her field.

In July 2022, León achieved another lofty distinction: Kennedy Center honoree. The gala ceremony, which includes fellow honorees George Clooney, Gladys Knight, U2 and Amy Grant, takes place Dec. 4 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and will be televised Dec. 28. On a video chat from her home in Nyack, N.Y., the now 79-year-old composer explained how one fateful plane ride forced her to reimagine herself several times over, throughout a singular career.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tom Huizenga: We spoke in 2021 on the day you won the Pulitzer for Stride, and you said then that the women's rights activists who inspired that piece had really taken a "failure is not an option" approach. I'm wondering if you had a similar idea in mind when you, at age 24, stepped onto that plane out of Havana.

Tania León: I come from a very poor family, a family integrated by people of different cultures. But what we had in common was the fact that we were poor and dreaming of something that was virtually impossible. It was my grandmother who got an idea that I liked music because of the way I reacted to music on the radio. She would tell me, "You're going to see your name in the marquees of the theaters." And I saw these people scraping pennies, literally, to provide me with my education. That man who bought me a piano when I was 5 years old — to this day I say, "Was he crazy?" You don't buy a secondhand piano for a child. But it was to provide us with the best education possible, and the talk was always positive: "You can do this, you can do that."

How did you decide you wanted to leave Cuba?

When I was 9 years old, I told my family that I was going to live in Paris, and they looked at me like I was nuts. I started trying to leave when I was 17. After struggling so many years, and finally getting the support of a family in Miami through the Catholic Church ... I got a telegram telling me that I was to fly on the 29th of May. And one of the things that happened boarding the plane — I didn't know that all of a sudden I was a citizen of the world, not a citizen of my country anymore.

Not long before you boarded, you learned that once you left Cuba you wouldn't be allowed to return anytime soon. What were you thinking?

First of all, I was in shock. Second, I felt I didn't have anything to do with the other Cubans on the plane, because I've never been into politics. They were talking about things that were none of my concern. And that is how I arrived here. I was very afraid.

Afraid of what — just the act of leaving itself?

My grandmother tried to persuade me not to leave. She had a tremendous hope that the Cuban Revolution was going to really be very good for everybody and for the country itself. She thought that if I stayed there, every dream I wanted to achieve was going to be possible. But I had already took the steps. I said to her, "Look, you gave me wings, and now you don't want me to fly." I said, "Remember, if things don't work out, I'll be back." And that was something that always ruminated in me — those words and the face of my grandmother — because I promised her something that was not possible. She died four years after I was here and there was no way for me to go back. I didn't have a visa, I didn't have permission to go to Cuba, to her funeral. It was absolutely devastating.

I'm glad that before she passed, your grandmother knew that you were firmly on your path to success in New York.

At least she knew by then that I had joined forces with Arthur Mitchell, and that I was a key member of the Dance Theatre of Harlem, something that she was really very proud of. Because my grandmother was a mixed-race woman. Her father had origins from Spain, her mother was one of the different manifestations of the African people, and she was always leaning toward the liberation of people of African descent.

I want to go back to your early years in New York. Beside the fact that you came without speaking English, there was upheaval in the U.S. at the time. Within about a year of your arrival, both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated. What did you think about all the unrest here?

I was petrified. Cuba is not that big, and Havana, even as the capital, is a small city in comparison to New York. I had no idea that this was going on here. I saw the marches of Martin Luther King on television for the first time in my life.

It was right after the assassination that I met Arthur Mitchell, in a chance encounter. It was my first time going to Harlem and to the Harlem School of the Arts — I went to replace a classmate who got sick. And that's the same day that Arthur Mitchell went looking for a place to start his project. He heard me play the piano, approached me and asked for my number. About two weeks after, I got this phone call from somebody speaking Spanish, telling me to go to the same place. And that was the first class of the Dance Theatre of Harlem — four female dancers with a barre in the middle of a sort of gym, and a piano, Arthur and I.

As you said, your original plan was to get to Europe. That was the goal for many American musicians of your generation, especially musicians of color, who felt more doors would open for them there. Do you ever feel you may have missed opportunities in Europe by staying here in the U.S.?

Not really, because I was part of a project that, for me, was incredible — the creation of a classical company where people of color would have the chance to really demonstrate that they could actually do this art form.

[Early on,] Arthur turned to me and said, "Why don't you write something, and I'm going to do the choreography?" And that became my first ballet. After that I went back to NYU — I was already there validating my degree as a pianist — and said, I want to change my major to composition. Because the first piece I wrote was instinctual, but I wanted to really know the techniques. I wanted to actually understand the art form.

That first ballet was Tones, from 1970.

Exactly — which is dedicated to my grandmother.

Speaking of writing music, I spoke with composer Julia Wolfe recently and she mentioned your name. She said, "It's been so much easier for me than, say, the generation before me — people like Joan Tower and Tania León and Meredith Monk, they really had to get the machete out and carve a path. Nobody was really, truly recognizing women composers in that generation." Did you ever feel that you had to work harder to get attention paid to your music?

We all have a brain. We all are capable of doing anything. We have talents that don't have anything to do with the way you look or your skin tone or how tall you are or how old you may be. That has been my mantra. So therefore, I've never accepted anybody putting me down because of something like that.

The motor behind my heart has to do with my grandmother, my grandfather — all these people that, while I was growing up, had so much faith in me. They believed so much in my talent. And as [classical music] came into the house, they embraced it and wanted to participate. I have no problem saying that my mother didn't know how to read and write, but she could recognize the piano concerto by Robert Schumann. To me that was incredible — to see that they were so invested in this, that they understood what was happening, musically speaking. You know, we all dance salsa, but we were also listening to and discussing these things on a very high level.

As I understand it, after you left Cuba, your music wasn't performed there until 2003?

I have no idea. The first person that I believe interpreted a work of mine there was [pianist] Ursula Oppens — I wrote a piece for her called Mistica. In fact, the day of her recital was Mother's Day, and after she premiered the piece Ursula stood up and asked if my mother was in the audience, and gave her the score because I had dedicated [the piece] to her.

Many composers who have left home put their yearning for their homeland in their music. Have you done that at all over the years?

It is not so much the entire island of Cuba, because, due to our financial situation, I don't know Cuba. I know a little bit of Havana. As a child, in school, they took us to see the Viñales Valley, so I knew a little bit of that province. I know Varadero because of the beach. And before I left Cuba, my mother took me to Sagua la Grande to say goodbye to her older sister. [But] I don't really know the country where I was born.

You said in an interview, "Composing is internal. Your music has to come from inside of you from that spiritual part, the part of you that really talks to you deeply." In your own work, how do you know when you've reached something profound?

Well, I am very close to my pieces. When I listen to them, I go to that moment of the sound — not the images or the places that connect me to a sound, but the moment of the creation of that sound. This happened with Stride: I was writing that piece and all of a sudden there's something like these gigantic steps — I felt them. I was writing the piece and this thing came into my mind.

I'm not a composer, but I imagine it must be an amazing feeling — like it's something almost bigger than yourself.

Exactly. All of a sudden, I heard this thing, and it was like seeing the marches of Martin Luther King again, and imagining the march of Susan B. Anthony. Every time people want to ask for something they feel they've been deprived of, they collect themselves and they march. That came in, and I trusted it. And the more that I wrote that passage, the more that I had the vision. I don't know how it works. I just hear this thing, I trust it, and put it on the paper.

Paper? Many composers these days use computer software to help them write out a score, but it sounds like you are old school — you still write directly on manuscript paper?

All these musical tools for us to work with now are fantastic, but I don't like the computer to tell me what to do. For me that's just mathematical — it doesn't have the movement. I mean, you and I are talking, and yet we have an incredible clock going that is in a different tempo, and that is a beating of the heart. Computers cannot breathe.

This might be a good time to talk about rhythm, because it plays a key role in your music. That role can be very obvious, like the Brazilian beats and instruments in your ballet Inura, or more complex, such as in a solo piano piece like Momentum. What is it about rhythm that fascinates you?

Rhythm has to do with my inner culture, the culture where I grew up. You go to Cuba, to Puerto Rico, you go to the Caribbean, this is something rhythmical. I worked with a musician in Europe who plays the kanun [zither]. He is from Turkey, and I felt very comfortable with what he was doing. Mentally I can hear the different layers and how they communicate. I think that has to do with the training we had — cultural training that is so rooted in rhythmical ambience.

One of my favorite pieces of yours is Horizons, the orchestral work you wrote in 1999 for a festival in Hamburg, Germany. I love how you described the piece — you said, "Rather than being in a fixed form, Horizons is more like a stream that widens and narrows unpredictably, following a winding course." I'm wondering if that description is almost a compositional philosophy for you? Because the music is meticulously thought out, but it sounds like a winding, unpredictable river.

Well, you just hit it on the nail. One of my dreams that I was able to realize is that there are pockets of that piece that are navigating in a different tempo from the majority, so all of a sudden you feel this rush. One of the composers that inspired me to do that was Charles Ives. It is my exploration, something that I really would like to continue doing, but I realize is very difficult for an orchestra because it requires a lot of rehearsals.

I want to note that you spent a few decades as an educator at the City University of New York's Brooklyn College, beginning in the mid-1980s. I know you're retired now, but what would you say is important for young composers to understand these days?

One of the things that I try to inspire in a composer from the very beginning is to get in touch with precisely what we are talking about — the internal drive that actually makes them write music. If you are compelled, it's because you feel that you have something to say in the world of sound. When you study the early works of any composer, there are traces that grow into the later compositions — you find the seeds there. So if you as a student want to get into this, you have to pay attention to what you're doing from the very beginning.

You'll be 80 next year, and in the run up to that milestone you've been recognized with two particularly big American awards: In 2021 you became a Pulitzer winner, and this July you were named a Kennedy Center honoree. Were there any little thoughts in the back of your mind wondering why these two awards didn't come earlier?

No, not really. In fact, I was surprised, because I have always been doing my own thing. Years back, we used to describe the different trends [in New York Music]: "uptown," "downtown," "midtown," whatever. And I always said that I was "out of town," because I knew everybody, I loved everybody. I was a good friend of John Cage. I remember when Julie [Wolfe] and David [Lang] and Michael [Gordon] started Bang on a Can. I was the first defender of Philip Glass. By the same token, I had a fantastic friendship with Charles Wuorinen, and have been sort of an assistant to Joan Tower from the very beginning. I mean, I love composers regardless of what they write — it could be Broadway or musical theater or electronics, it could be anything. They are the kings and queens of sound.

I ask the question because when you won the Pulitzer, I heard many people saying the same thing: "It's about time."

I heard that. People wrote me and said: "Long overdue." When I got the call from Kennedy Center, I was ready to say, "Are you sure it is me?" Because I have not played the politics — I have never put my name into any competition, so they have been real surprises to me. Those things don't determine the way I want to write, or the way I'm going to be manifesting myself as a musician. How much longer am I going to be on this planet? I don't know. I'm not concerned about that. I keep going.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.