Section Branding

Header Content

8 listeners share the powerful ways they keep in touch with their ancestors

Primary Content

How do you stay in touch with your ancestors?

Last month, we asked our audience to tell us about their relationship with family members who have passed away. And we were overwhelmed by their beautiful responses.

A dad tells us about a blue die he keeps because he believes it was given to him as a gift by his late son. A woman tells us about the altar she created to pay homage to her Icelandic heritage. And an artist explains about how she honors the relatives she lost in the Holocaust: by creating artwork about them.

Here's a selection of their moving tributes and stories. These responses have been edited for length and clarity.

'The last gift I ever got from my son'

On the day of my son Eric's funeral, who was 31 when he died, I was getting ready and I heard something hit the floor. I looked down and there was a blue die there that I had never seen before. My house is very clean and clutter-free, so it was as if it fell from another dimension.

I never did figure out where it came from. But as far as I'm concerned, it came from him. So I keep this die in a black dish in the bathroom where I get ready for work each day. I see the blue die and it reminds me of him. And it's just the last gift I ever got from my son. —Jeff Stout

They call on their ancestors in big life moments

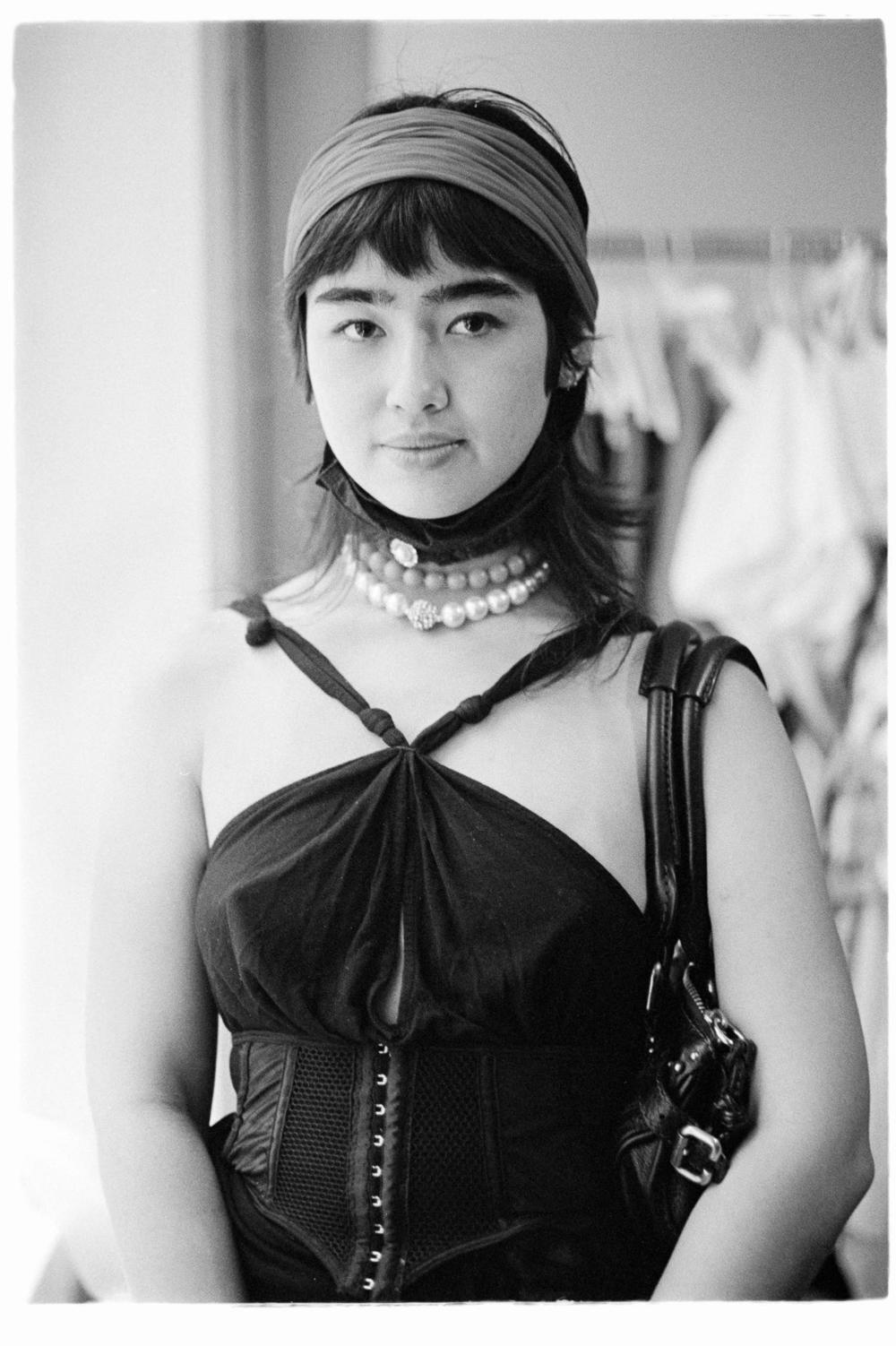

I am an only child of mixed race — I am Chinese and white from Australia — and I've been living in the U.S. without my parents since I was 15. [I have this] comfort thing [that I do with my ancestors] to bolster me in [big life] moments.

When I have so much emotion inside me, either good or bad, I envision it shooting out into the universe as a signal [to my ancestors]. Then once I've signaled them, I [picture] all these faceless figures gathered around me.

It's kind of like an energy or a vibe that I've imagined for myself. So for example, if I get an amazing job offer, instead of just texting my mom or dad, I'll [share the news with my ancestors]. Those people are there and you can bring them around whenever you need them. —Alyson Cox

She makes 'personal time' to celebrate her grandma

On the day of my [grandmother's] passing, I don't schedule plans with anyone. This is for me to have personal time with my grandma.

I make Korean zucchini pancakes and potato chips that my grandma used to make for me whenever I went over to her place. And I write a letter to her in my journal. I try to write these in Korean because I want to make sure she understands what I'm saying. [I try to imagine that] I'm having a conversation with her — and think of how she might advise me on some of my hardships with warmth and love. —Alicia Lee

An altar that started out as a tribute to his late wife

After losing my wife Teresa [in 2019], I built two console tables where we keep pictures of her and our family, flowers and religious symbols. They are beautiful reminders of her.

Then when my father passed away in [2021] I began to think about a creating a place where I can keep objects that remind us of those who have died recently and many years ago. I began our ancestral altar earlier this year. The objects relate to my wife, my father, my mother- and father-in-law and my grandparents. Each of the objects has many layers of meaning and symbolism.

They are all kept in a secretary, given to my great grandparents as a wedding gift in 1910. —Paul Manley

A connection to her Icelandic heritage

My mother immigrated to the U.S. from Iceland in 1971. Even though I was not born in Iceland and I did not grow up with the language, I strive to stay connected with my ancestry by teaching myself Icelandic, traveling to Iceland as much as I can, staying in touch with my cousins, aunts and uncles [who live in Iceland] on social media and learning about the culture and history of Iceland.

I keep a little altar in my house and decorate it with reminders of my ancestry, such as photos of my grandparents, flowers and other things. It also has a photo of my maternal grandmother, Kristín Elín Théodórsdóttir, and behind her is a cat that she embroidered in 1929 and gave to me as a Christmas gift when I was a child. —Lilja Klempan

'It allows me to remember who I am'

I started an ancestor practice in 2020 to help me deal with depression and anxiety. I light incense and list all the things I am grateful for in this life.

I say the names of my ancestors, going back to my great grandparents. I also say the names of aunts, uncles, cousins and friends who have passed on. I then pray that they help my mother, who languishes in a memory care ward with advanced Alzheimers. I then meditate to understand what kind of thoughts and feelings are running through my mind.

This practice has helped me in a multitude of ways, mostly in making me feel purposeful, grateful and connected to my people. It allows me to remember who I am and where I came from. —Sunny BenBelkacem

'It makes me happy to teach him that our ancestors live on'

We created an ancestral altar for Día de los Muertos to honor my father, Eduardo Quiñones, who passed in 2021. Even though I didn't grow up making altars in my home in Tijuana, Mexico, it is now an important annual tradition in my own home in California. I struggled with whether to take the altar down this year, but when my four-year-old son Beni asked me to keep it up, I happily obliged. It makes me happy to teach him that our ancestors live on. —Daniella Quinones

'I keep their memory alive through my artwork'

I sometimes question the process of remembrance when there are no memories. So many of my ancestors are lost, forgotten or hidden. My nana escaped the Nazis. She had to leave everything behind in Vienna, Austria. Her parents and grandparents were murdered in the Holocaust.

If it were not for them, I would not be here. I would like to pay my respects to their resting places but unfortunately, there are no burial plots for them. So I keep their memory alive through my artwork. Through this process I honor them. My ancestral artwork has become my version of their gravestones. —Marina Heintze

Thank you to all those who responded to our callout.

The digital story was edited by Beck Harlan. We'd love to hear from you. Leave us a voicemail at 202-216-9823, or email us at LifeKit@npr.org.

Listen to Life Kit on Apple Podcasts and Spotify, or sign up for our newsletter.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.