Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia Today: Hawks president stepping down, Georgia's WWII Heritage City, NE Georgia airport rehab

Primary Content

LISTEN: On the Friday Dec. 23 edition of Georgia Today: The Atlanta Hawks' president is stepping down; Georgia has a new World War II Heritage City; Gainesville's airport is getting a makeover.

TRANSCRIPT:

Peter Biello: Welcome to the new Georgia Today podcast from GPB News. Today is Friday, Dec. 23. I'm Peter Biello. Coming up on today's episode: The president of the Atlanta Hawks is stepping down. One of Georgia's cities has been added to the list of World War II heritage cities. And as we move closer to the year's end, we'll take a look back at some of these most memorable stories that you may have missed. That's all coming up on Georgia Today.

Story 1

Peter Biello: City officials in Northeast Georgia's Gainesville have approved a $5 million rehabilitation project for the city's airport. The project will improve the airport's runway, and most of the funding for it will come from the Federal Aviation Administration. Agency records show the airport had 38,000 takeoffs or landings over the last 12 months, almost all of it general aviation. Officials say the airport is important for economic development, making the community accessible for corporate jets.

Story 2

Peter Biello: The Atlanta Hawks said this week that its president, Travis Schlenk, is stepping down and moving into an advisory position and general manager Landry Fields will assume control of daily operations. The move comes after Fields was promoted to general manager earlier this year. Schlenk was hired in May 2017 and took the lead in rebuilding a team which won only 24 games in the 2017-2018 season. Schlenk will report to principal owner Tony Resler in his new role. The Hawks made it to the Eastern Conference finals in 2021, but are 16 and 16 so far this season.

Story 3

Peter Biello: The National Park Service has added Savannah to its list of World War II heritage cities. GPB's Benjamin Payne reports.

Benjamin Payne: The honor commemorates communities where the civilian workforce played a pivotal role in the war effort. For Savannah and Chatham County, that role was driven in large part by the Port of Savannah, which shipped about one and a quarter million tons of supplies and weapons. In addition, local shipbuilders churned out minesweepers and cargo vessels, and local citizens bought enough war bonds to purchase a B-17 bomber, aptly named "City of Savannah." The selection by the National Park Service is especially meaningful as each state can only receive a single World War II Heritage City designation. The agency also commended Savannah for its numerous memorials and monuments to World War II service members and civilian workers. Among the other Southern cities added to the list this month are Pensacola, Fla. and Oak Ridge, Tenn., just outside Knoxville. For GPB News, I'm Benjamin Payne in Savannah.

Story 4

Peter Biello: And we'll turn now to GPB's Sofi Gratas for one of the stories you may have missed this year. Many rural counties in Georgia don't even have one primary care physician. And that's a problem in a state that ranks near the bottom in multiple health indicators. But some programs in South and middle Georgia have actually been successful in bringing doctors to places that don't have enough.

Sofi Gratas: The town of Moultrie sits in the middle of Colquitt County. It's emblematic of most small Southern towns with a historic square, one Piggly Wiggly and miles of farmland on the periphery. Moultrie also has the only hospital in a county of about 45,000 people. That's Colquitt Regional Medical Center. It offers the only specialty care within an hour's drive. Without the hospital, things like obstetrics and cancer treatment would be nonexistent in the area. But now, through the hospital's new residency program, Colquitt County has three additional psychiatrists — the first to be trained in Moultrie.

Anthony Cimino: I see it personally as a benefit for me because I'll be able to secure a position here after residency.

Sofi Gratas: Anthony Cimino is happy to be one of those new psychiatrists.

Anthony Cimino: Actually, that was one of the attracting features to me, was to join a brand new program and like be the inauguration class. I loved that aspect of it.

Sofi Gratas: Colquitt County is officially a medically underserved area. That's a federal designation based on death rates, poverty and doctor-to-patient ratios. Over half of Georgia counties fall below state averages for per capita access to primary care, and 141 counties, both urban and rural, are medically underserved. In a 2020 survey of students from five Georgia medical schools, only about a quarter of students wanted to practice at a rural hospital in an underserved community. Far more expressed interest in what the survey called inner-city practice. But Colquitt Regional has managed to keep seven doctors on full time after the family medicine residency since the program's start in 2016. That's because some people just like it here. Jermaine Robinson graduated from residency this year and is staying on as a hospitalist.

Jermaine Robinson: Everyone is just so welcoming. And I love that feeling and I wanted to keep that feeling.

Sofi Gratas: And second-year family medicine resident Rickey Patel says. If he doesn't stay at Colquitt, he's likely to continue his practice in North Georgia, another area that's lacking doctors.

Rickey Patel: I mean, I like the community and it is good to be able to see some of your patients just, you know, out and about in the town. And then they come in and it just helps build a better patient relationship.

Sofi Gratas: Plus, rural residency programs typically aren't as competitive as other ones. Residents don't have to fight for slots and medical rotations where they work with attending physicians on surgeries, deliveries and other types of primary care.

Rickey Patel: We get better training as far as procedures go because there's no one else, you know, we are it.

Sofi Gratas: But there are challenges to being a rural doctor, too. For one, doctors can be overrun with patients. And smaller cities might not offer as many amenities or job opportunities for spouses or family. Some federal and state programs offer financial incentives in exchange for a stint in rural, underserved areas for these reasons. OB-GYN Sheena Favors works in Albany, serving patients from surrounding rural counties. She says cities need to do their part in keeping doctors around, even after those program incentives are gone.

Sheena Favors: That's the little piece that I think a lot of rural areas haven't really figured out: What can they do to bring people to the city, to see the city, to explore, and come here to visit, to see if they like it and be like, "Oh, maybe this is a place I could live."

Sofi Gratas: Back at Colquitt Regional Medical Center, psychiatry resident Anthony Cimino says the town of Moultrie is growing on him.

Anthony Cimino: I've lived in urban areas my whole life, New York City for a while. I was used to that fast pace. Go, go, go. Rat race mentality. But honestly, I — I'd had enough of it, you know?

Sofi Gratas: So odds are after residency, he'll stay. For GPB News, I'm Sofi Gratas in Macon.

Story 5

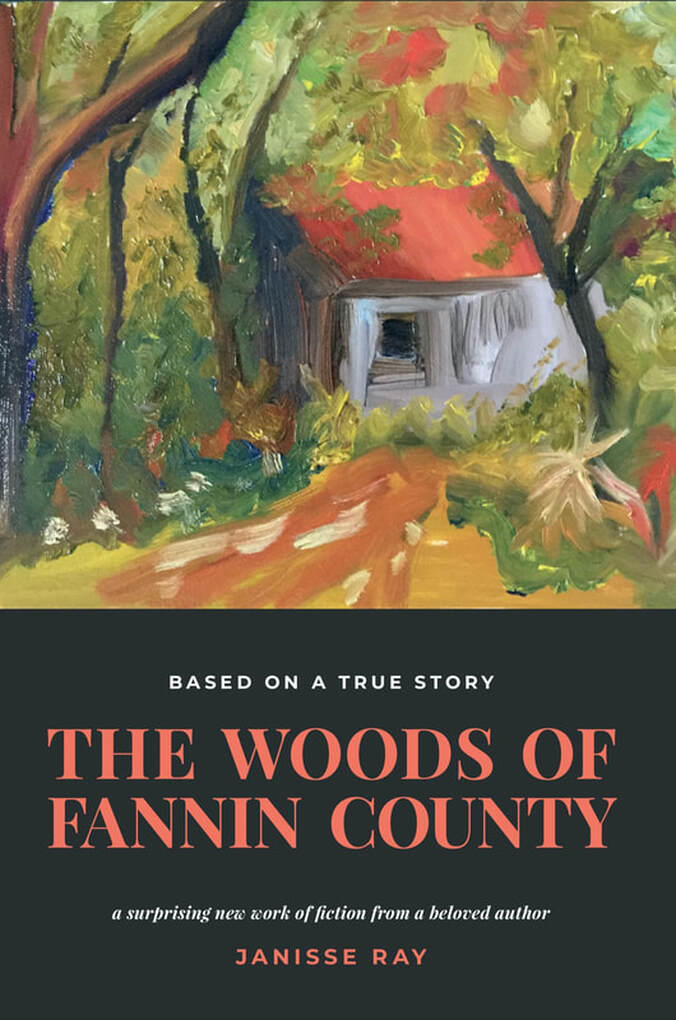

Peter Biello: In the 1940s, eight children were taken into the North Georgia mountain woods and left to die. They survived. And now their story is a page-turning novel. GPB's Orlando Montoya talks to author Janisse Ray.

Orlando Montoya: South Georgia writer Janisse Ray has released her first novel. Ray is best known for her 1999 literary breakthrough Ecology of a Cracker Childhood and other memoirs and essays about nature and the environment. The Woods of Fannin County marks her first work of fiction. It's based on a true story about eight children who, in 1945, were taken to a remote shack in the mountains of North Georgia and abandoned. They survived there by themselves for four years. It's a harrowing story about hope and resilience. And Ray joins me now to talk about it. Thanks for joining me.

Janisse Ray: Thank you, Orlando.

Orlando Montoya: How did you come to know about this story?

Janisse Ray: I was raised in a little town in South Georgia called Baxley and the Georgia Baptist Children's Home was there. And that was the orphanage where these children were taken when they were rescued. So one of the children grew up and owned an antique store in town. My dad was visiting him one day, and for some reason Mr. Woods was ready to tell his story. It was something that he hadn't talked about really ever. And he told my dad. And my dad called me instantly the minute he got home and said, "there's a story you need." You know, once you're a writer, everybody's telling you these great stories. So I went with my father and mother on a Sunday afternoon to visit Mr. Woods. He had brought his sister in from Alabama, and they told me their story.

Orlando Montoya: How much of the book is true and how much of it is your imagination?

Janisse Ray: This is a a question a lot of people ask me, Orlando. Every bit of it is true. What happened, though, is that the children were so young when they were taken — he oldest was 10 and the youngest was a newborn — that, you know, in the way of children, they didn't remember many exact details, but they would say to me, "well, we cleaned out the fireplace and there was a snake in the fireplace." So I would just keep asking questions like, "Well, what kind of snake was it? What color was it?" And a lot of times they didn't know and they would say they didn't know. And the liberty that I took with this as a novel would be in filling out the details. But the story itself, the scenes themselves, all those things happened.

Orlando Montoya: How did these children survive? I mean, you could take that as a big question or a small question. I mean, obviously, they survived by finding food or finding shelter and all number of things that we know about survival. But how did they survive with a capital "S"?

Janisse Ray: Well, they definitely believed in each other. They were not going to lose any of them. And in terms of of exactly how they survived, they did it by ranging the woods, eating Paul Pauls, which they called hollyhocks and all kinds of nuts, like hickory nuts and pig nuts. But they also learned to steal. They stole from apple trees, from root cellars. They're incredibly resourceful.

Orlando Montoya: But the townspeople knew they were there. Everybody knew they were there. It was sort of like a collective — a collective guilt on everybody that these children were abandoned.

Janisse Ray: It was definitely a collective abandonment. I wouldn't say the entire town knew, but multiple adults did know, including the mother and the father — who were divorced from each other, and he still lived in Michigan and — and Orlando, I think it's also important to say that they weren't 100% abandoned. The mother would come back up to the cabin and check on them. The longest time they believed that she was gone was four months. But in general, they would say to each other after about three days, you know, it's time for mama to come home. And she would she would come home and make another very large vat of hominy in a kettle outside. And then she would leave again. They did not talk about this until they were adults. And when they finally all got together — it was a Thanksgiving; all were grown and they met at one of their homes and they began to talk and and they all came to the conclusion that they were put there to die. So there's no excuse for what happened. But she didn't abandon them fully.

Orlando Montoya: I like your choice of language in the story. Galax, meaning a type of herb. Timothy, meaning a type of grass. Ramp, meaning a type of wild onion. These are not words that you can study in order to sound smart using, you have to know them. How did you learn about the natural landscape in this story?

Janisse Ray: I went to undergrad at North Georgia University in Dahlonega. It was in the mountains. And so, you know, in a person's life, that place where you come of age embeds very deeply in your psyche. And for me, it was the Blue Ridge Mountains of the Appalachians. But once I was really working on the book in a deep and pointed way, I just did a lot of research and a lot of visits back up to the area.

Orlando Montoya: What did you see on your visits?

Janisse Ray: I couldn't find the cabin itself. You know, it had a distinctive stone fireplace. So it I think stones from the fireplace would have to still remain somewhere. But I was never able to find it. And in fact, some of the children have returned and they report the same. But isn't that true for many of us, that the world is changing, the human environment is displacing the natural environment at such a rate everywhere across the globe that often we can't go home again because "home" just can't be found.

Orlando Montoya: There's a lot of cruelty in the book, but a lot of hope as well. And I'd like to lift up two sentences that-that spoke to me: here Bobby, the oldest child, is talking about his grandmother. "Sometimes I think maybe all the meanness started with her like she was a fire and the flames crept along next to the ground and he don't even know it's spreading until you see smoke rising a few feet away. But I think life would be a lot harder if you could see everything burning around you, burning down your life." What does this story say about surviving that type of fire?

Janisse Ray: I think that we have had a romanticized notion of motherhood often in this country. I did not write this book to address the MeToo movement or Roe v. Wade. Not at all. But I think that we can't assume that all children born are planned and wanted. And Orlando, that's been a very surprising reaction. I get a lot of mail from people who had some kind of similar thing happen to them, that they were given up by their parents, but their grandparents raised them or they were in an orphanage. We just have to be very particular in how we romanticize or characterize motherhood and fatherhood.

Orlando Montoya: Janisse Ray wrote The Woods of Fannin County. Thank you for talking about it with me.

Janisse Ray: Orlando, your questions were brilliant. Thank you for reading it. And the pleasure is all mine.

Peter Biello: And that's it for today's edition of Georgia today. For more news from GPB, you can subscribe to our newsletter at GPB.org/Newsletters. You can also visit our website any time. Just go to GPB.org/News for the latest from our newsroom. Your feedback is appreciated, of course. You can send it to us by email. The address is GeorgiaToday@GPB.org.

I'm Peter Biello. Have a great and restful weekend. We'll see you on Monday.