Section Branding

Header Content

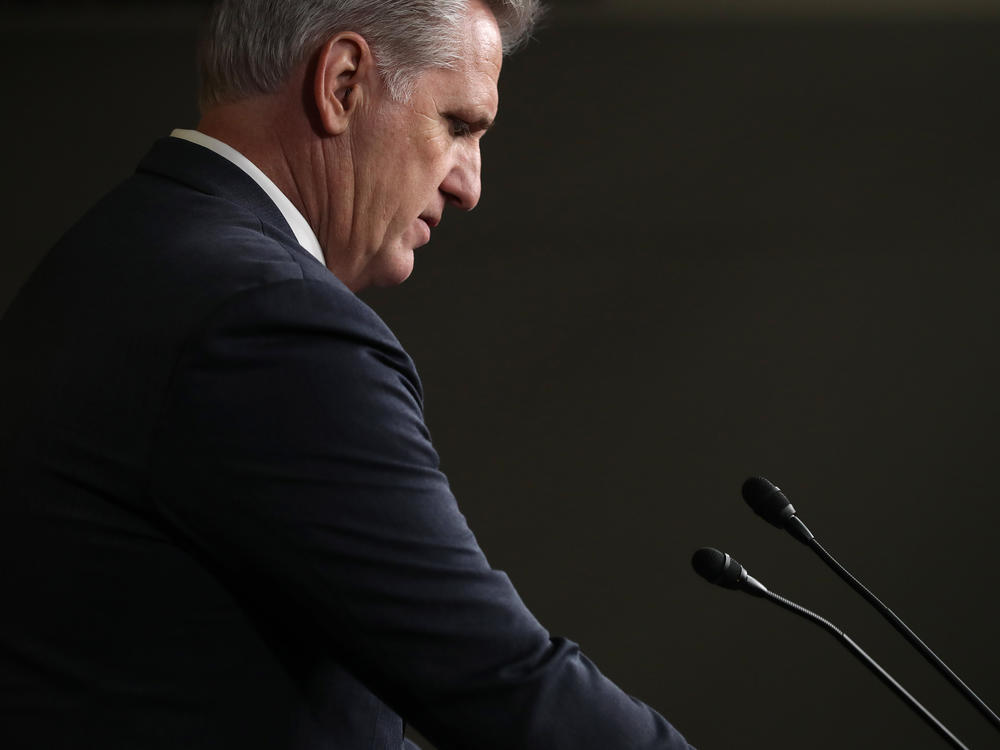

This was supposed to be Kevin McCarthy's moment. Instead, GOP chaos reigns

Primary Content

Updated January 4, 2023 at 10:00 PM ET

This one had to hurt.

"Maybe the right person for the job of speaker of the House isn't someone who has sold shares of themself for more than a decade to get it," Matt Gaetz, the hard-right Florida congressman, said on the House floor before nominating Ohio Rep. Jim Jordan for speaker before a second round of voting Tuesday.

This was supposed to be Kevin McCarthy's moment, one he had contorted himself into political knots to get to.

The California congressman has wanted to be speaker — badly — for years. He seemed willing to do a lot of things to get the job, including burrowing into former President Donald Trump's good graces.

But none of it has been enough. Congress adjourned Tuesday without McCarthy — or anyone — as speaker after three ballots of voting, the first time the voting has gone beyond one round in 100 years. McCarthy lost an additional three rounds on Wednesday without a resolution.

The House without a speaker cannot move forward, no other votes can be held, no legislation can be considered. How this gets resolved is an open question — either McCarthy somehow wins over the hard-right members who are steadfastly holding out against him or he bows out, clearing the way for someone else.

Who that is, however, also isn't clear.

It's an untenable position for the country. But how we got here is something of a Washington tragedy — for McCarthy and for governance.

From Benghazi to Trump

Republicans — and McCarthy — have been here before.

The rise of anti-establishment intransigence among a hard-right faction in the GOP can be traced with a straight line back to the Tea Party — and put on steroids by MAGA Trumpism.

In 2010, Republicans rode the Tea Party wave to win control of the House, but the cost was steep. Fights over raising the debt ceiling – something that had been routine and protected U.S. credit — and five years of an inability to get much of anything done, even with each other, frustrated John Boehner as speaker.

Back then, McCarthy was the expected successor. But that effort was derailed — by himself.

"Everybody thought Hillary Clinton was unbeatable, right?" McCarthy said on Fox News. "But we put together a Benghazi Special Committee, a select committee. What are her numbers today? Her numbers are dropping."

Whoops.

The ostensible reason for the GOP-led Benghazi investigation was to find out what happened in an attack on an American embassy in Libya, where four people died — not to hurt Clinton. But Clinton, who was secretary of state in the Obama administration, was the front-runner for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination.

McCarthy said the quiet part out loud.

It was a head slapper. He was contradicted by Boehner and others. McCarthy had to go back on Fox News and backtrack.

But the damage was done.

After all, the speaker of the House, in addition to conducting the House's business and being a key cog in the process of passing legislation important to people, is also a leader in party messaging.

McCarthy, someone the right was already skeptical of, was viewed as anything but a great messenger for the party.

Along came Trump

McCarthy, who was trying to claw his way back to the political limelight, hitched his wagon to the then-president.

"Where's Kevin?" Trump said at a luncheon days into his presidency. "There's my Kevin."

My Kevin.

It was a clear sign that McCarthy had gotten himself into Trump's good graces.

McCarthy knew Trump — and winning over the hard right, of which he is no founding member — was his path to power.

That's why McCarthy didn't believe he could stick to his criticism of Trump after Jan. 6, heading down to Trump's Florida home just weeks after the insurrection and posing for a photo with him.

The pair were able to use each other — Trump for normalizing what he did Jan. 6 and in the runup; McCarthy for the speakership.

Trump maintained his power with the base and endorsed scores of candidates in the 2022 midterms. They did well in primaries, but many lost in competitive swing districts.

There is a great irony to the fact that had there actually been a red wave and Republicans won more seats, McCarthy could have had enough votes to win the speakership and wouldn't even be in this position.

Over the last seven years, McCarthy has tried to court the hard-right faction in his conference

In the runup to the speaker vote, McCarthy tried everything. He tried to acquiesce to the hard-right's demands — even willing to give the faction the ability to remove him from the speakership if they didn't like the job he was doing.

At the 11th hour, he tried to play tough guy, threatening the defectors with stripping them of committee assignments. That appeared to have the reverse effect of what he and his allies were intending.

And that was all after years of placating these members and walking a tortured line as GOP majority leader in dealing with them.

But none of it worked. Even Trump hasn't been able to win over the Never Kevins.

There's some question how hard Trump actually tried. On the day of the vote, and in the days leading up to it, for example, he hadn't posted anything on his social media platform to boost McCarthy.

Trump did post Wednesday, however, implying that he spoke with members Tuesday night and encouraged them to vote for McCarthy.

"[I]t's now time for all of our GREAT Republican House Members to VOTE FOR KEVIN, CLOSE THE DEAL, TAKE THE VICTORY," Trump said, in part, reserving his ire for Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell. Trump added, "REPUBLICANS, DO NOT TURN A GREAT TRIUMPH INTO A GIANT & EMBARRASSING DEFEAT. IT'S TIME TO CELEBRATE, YOU DESERVE IT. Kevin McCarthy will do a good job, and maybe even a GREAT JOB."

For all of McCarthy's contortions, backtracks and acquiescence, he's still short of what he needs to be speaker, the job he's wanted for so long.

The hard right has long been skeptical of McCarthy, and he — to this point — just does not have their trust.

The question now is — not just for McCarthy but for anyone who has ambition and has to make choices between what they believe and what they're willing to compromise — was it worth it?

At the end of the day, the job of speaker isn't supposed to be about one person's ambition but what they can get done to fix problems in the country, and this is taking place at a time when people are already cynical about the intentions of politicians in Washington and what they are trying to accomplish.

For all the talk in Washington of "Dems in disarray," this is again another example of the chaos that continues to surround House Republicans. With just a four-seat majority, how can they govern if they're going through all this just to pick a leader?

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.