Section Branding

Header Content

She was denied entry to a Rockettes show — then the facial recognition debate ignited

Primary Content

One evening in late November, New Jersey attorney Kelly Conlon was chaperoning her daughter's Girl Scout troop to see a Rockettes show at Radio City Music Hall.

Soon after arriving at the historic New York City venue, she was pulled aside by security and asked to confirm her identity. They told her their facial recognition system already knew who she was, and more importantly, where she worked, Conlon told The New York Times.

She was denied entry.

The issue was her law firm was involved in litigation against Radio City Music Hall's parent company, Madison Square Garden Entertainment (MSGE). As a result, Conlon — as well as lawyers at other firms pursuing litigation against MSGE — had been placed on an "exclusion list" at a string of popular venues owned by the group.

The story has become a flashpoint in the debate around facial recognition technology. While proponents say it has the ability to keep people safer, critics counter that there is little to support this idea, and warn that unchecked use of the technology could have untold consequences.

"Experts believe that facial recognition is so uniquely dangerous, and is something more akin to nuclear or biological weapons, where it's so profoundly harmful, it has such an enormous potential for harm to our basic human rights, [and] to people's safety," says Evan Greer, the director of Fight for the Future, a digital rights organization.

How does facial recognition software work?

Facial recognition is a form of biometric surveillance that works basically by comparing two images to each other, says Greer.

"You have a database of targets, and then you can use an algorithm to sift through footage or still images," they said. "Or in [Conlon's] case, they were doing real-time facial recognition, where effectively the surveillance cameras in the venue were constantly being analyzed by software looking for specific people."

It doesn't take much to add a new person into the system, Greer said. Taking a headshot from a company website, a mugshot from an arrest database, or even a screenshot from a social media profile can be enough for the algorithm to target and then attempt to identify a person.

When asked about Conlon's case, MSGE said its policy was to not allow attorneys from firms pursuing active litigation, regardless of whether the individual lawyer was involved in the case.

"While we understand this policy is disappointing to some, we cannot ignore the fact that litigation creates an inherently adversarial environment," MSGE said in a statement. "All impacted attorneys were notified of the policy. We continue to make clear that impacted attorneys will be welcomed back to our venues upon resolution of the litigation."

Currently, facial recognition technology is legal in New York City. There is no federal law that specifically deals with facial recognition, leaving some places like San Francisco, Boston, Portland and the state of Illinois to pass varying types of regulation or bans on the tech in the last few years.

This slow crawl of patchwork regulation at a state level worries privacy experts.

For one, it's the simplicity of adding targets to a database that makes this technology so potentially dangerous for user privacy, says Albert Fox Cahn, the executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (STOP) based in New York. Then there's the fact that biometric data is unique to your features — and permanent.

"You can change your name, you can change your social security number, you can change almost anything, but you can't change your face," Cahn said. "So if your biometric data is compromised once, it's compromised for life."

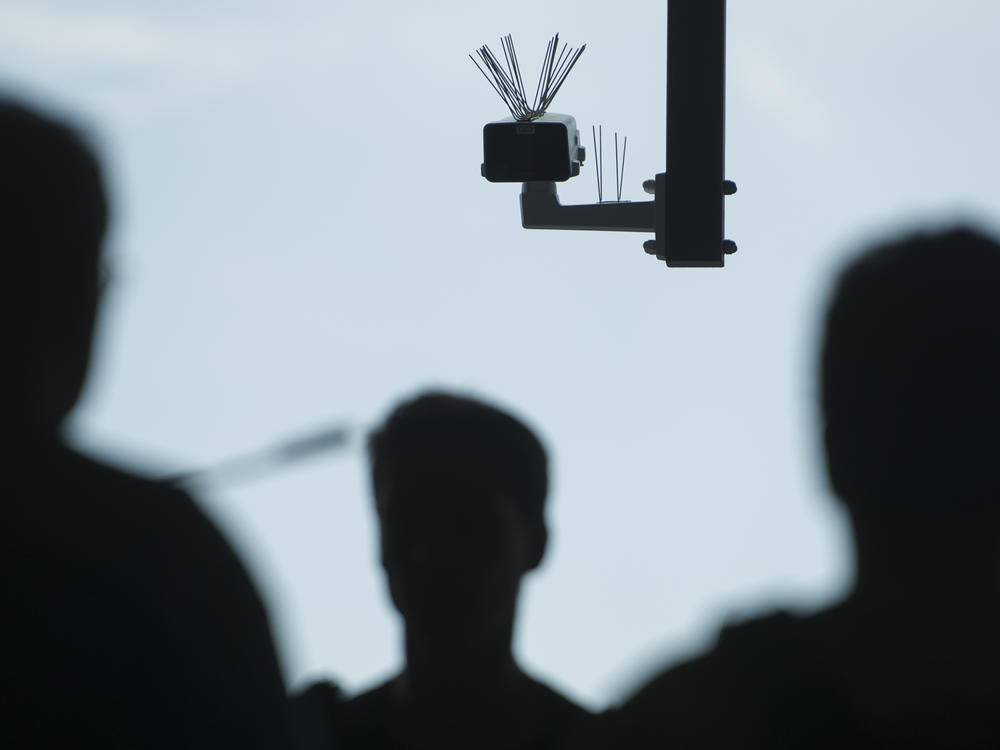

There are also concerns about who could potentially suffer most from the technology. While there are signs at MSGE venues stating facial recognition is being used for security purposes, critics say that there hasn't been much evidence of the tech upholding that purpose.

If anything, flaws inherent in the software exacerbate existing discrimination towards minority groups, putting them at a higher risk of being falsely accused of crimes, says Hannah Bloch-Wehba, an associate law professor at Texas A&M who specializes in privacy, technology, and democratic governance.

"Facial recognition technology tends to misidentify people of color, and in particular, women of color," she said. "And so I could see a serious concern about the sort of racial and gender bias implications of this kind of tech being used to screen people."

Some versions of the tech have shown to be less adept at differentiating between people with darker complexions in the past. And Greer says that traditional law enforcement surveillance has also historically led to the over-policing of communities of color. They fear combining the two could lead to an amplified effect.

"Because of the legacy of racism within policing in the United States, arrest databases are disproportionately filled with the faces of Black and Brown people, and particularly Black men," she said. "If you get stopped, and they scan your face with facial recognition, you're simply more likely to get a match if you're a Black man than if you're a white man because of that kind of racist legacy that's now being exacerbated using this technology."

Over the past few years, a number of Black men have been falsely identified as suspects in criminal investigations that used facial recognition software, in some cases resulting in wrongful arrests and charges.

In Detroit, a Black teenager was kicked out of a roller rink in 2021 after facial recognition technology mistakenly identified her as someone who had previously gotten into a fight at the property.

"We may hear these high profile stories about attorneys," says Greer, "But in the end, we know that this technology is disproportionately used on marginalized communities, and disproportionately harms marginalized communities."

A question of safety

In a statement to NPR, MSGE said facial recognition technology was widely used throughout the country, including in the sports and entertainment industry, and in shops, casinos and airports "to protect the safety of the people that visit and work at those locations."

"Our venues are worldwide destinations and several sit on major transit hubs in the heart of New York," it said. "We have always made it clear to our guests and to the public that we use facial recognition as one of our tools to provide a safe and secure environment for our customers and ourselves."

To critics like Bloch-Wehba, the idea of safety requires more nuance.

"We have to ask, who are you trying to keep [patrons] safe from?" she said. "How are you deciding who poses the threat? Is that a decision that the management of the venue is making, or is it a decision that the technological product is making? And who is checking that decision?"

Fox Cahn says that a lack of regulation for facial recognition technology in New York City leaves him unsurprised by the recent headlines that garnered so much attention.

"New York has given businesses free rein to use facial recognition in their properties. And it was only a matter of time before we saw owners using it to retaliate this way," he said.

STOP, and other advocacy groups like Amnesty International and the Immigrant Defense Project, are working towards legislation that will curb the use of this software in public places in New York, and hope for a federal ban down the line as well.

The process hasn't been quick, which Fox Cahn said added to the challenge of keeping up with the ever-evolving technology.

He said many New York City lawmakers were eager for regulation, but that he believed some people at the city council were blocking progress. He attributed the lack of support to concerns some politicians may have about clashing with the New York Police Department and the companies that supply the city with this kind of technology.

Tiffany Cabán, a city council member representing New York City's 22nd district, sees a clear connection between political will and maintaining the status quo.

"Part of it is the age-old tale of money in politics," she said. "If you are pumping money into the system and people see themselves as accountable, or [see that] your contributions are responsible for them holding their office, or being in a position of power, then it's not going to be in their best interests to push forward legislation that inhibits those folks' ability to do the things that they want to do."

A former public defender, Cabán recalls faulty technology being used as evidence in criminal cases, and she would like to see it banned.

"There have been efforts to introduce and pass legislation that increases police accountability. And I think that legislation surrounding facial recognition would be part and parcel to that," she said. "So I am hopeful at least that we will see some of those things coming out and in this next year that we've just started."

The call for law and order is strong

The divide among New York politicians starts at the top, with Mayor Eric Adams advocating the technology in a recent POLITICO interview.

Adams, a former NYPD captain, campaigned on a platform of public safety, and sees facial recognition technology as one tool in his arsenal.

"It blows my mind how much we have not embraced technology, and part of that is because many of our electeds are afraid," Adams said. "Anything technology they think, 'Oh, it's a boogeyman. It's Big Brother watching you.' Big Brother is protecting you."

The NYPD is also no stranger to the technology. An FAQ on its website states it has been using facial recognition since 2011 to identify suspects in various types of crimes.

"[The NYPD] knows of no case in New York City in which a person was falsely arrested on the basis of a facial recognition match," the FAQ reads.

"Safeguards built into the NYPD's protocols for managing facial recognition, which provide an immediate human review of the software findings, prevent misidentification."

Jake Parker is the senior director of government relations for the Security Industry Association, a trade association for security companies, and advocates the use of facial recognition technology.

Amid the criticism of MSGE's use of the tech in the Conlon case, Parker said its enforcement demonstrated some of the potential security benefits, too.

"It makes me think about how many times someone subject to a restraining order showed up without warning at a workplace and committed violence despite the restriction. And unfortunately, this happens all the time, and women are often the victims," Parker said.

He believes the tech can help secure public spaces like schools, airports, music venues, and other places that may require identity verification — as well as make them more efficient.

"With almost any application of facial recognition, it is augmenting and helping a human control process become faster, more accurate," he said.

"The position of the technology leaders in this space, we believe any technology, including facial recognition, should only be used for purposes that are lawful, ethical and non-discriminatory."

Both Parker and the NYPD refute the claims that people of color are more likely to suffer from this software.

The NYPD says people identified by the technology are routinely reviewed, meaning "erroneous software matches can be swiftly corrected by human observers."

Parker, meanwhile, cites studies from the federal government's National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

"You look at the most recent data from the federal government's evaluation program, which most of the leading providers participated in, the top 150 technologies are more than 99% accurate overall, and even across Black, white, male and female demographics," Parker said.

A spokesperson for the NIST's facial recognition team said this interpretation of their data appeared to be correct, but they noted the studies were done in lab settings, with dedicated lighting and cooperative participants.

"Without this cooperation we'd expect, as shown in our testing, the 99% value to decline," they said in a statement. "NIST testing on cooperative subjects has shown improvement in demographic difference performance. Issues with image capture, such as lighting, can still exist and impact performance."

The possibility of widespread regulation for facial recognition technology is a top priority for activist groups, not only because it could curb scenarios like the one at Radio City Music Hall, but because who it applies to could be hugely impactful.

Bloch-Wehba says that there is already more existing regulation around facial recognition technology for government and law enforcement use in the U.S. than there is for private businesses.

"If we just were to regulate police use of facial recognition, but any private agency or business can use it however it sees fit, then that creates a dynamic where we've allowed the private sector to, in some ways, become more powerful than the government itself," Bloch-Wehba said.

This past week, New York lawmakers rallied outside Madison Square Garden in protest of MSGE's policy, saying another person had been ejected at a venue.

Meanwhile, a number of law firms are now suing MSGE over the policy, with the cases working their way through the courts. The outcomes are being closely watched.

"The decisions that we make about technology and the policies that govern it are going to shape not just the next 10 years, but the entire future of human civilization," says Greer. "The stakes really are that high."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.