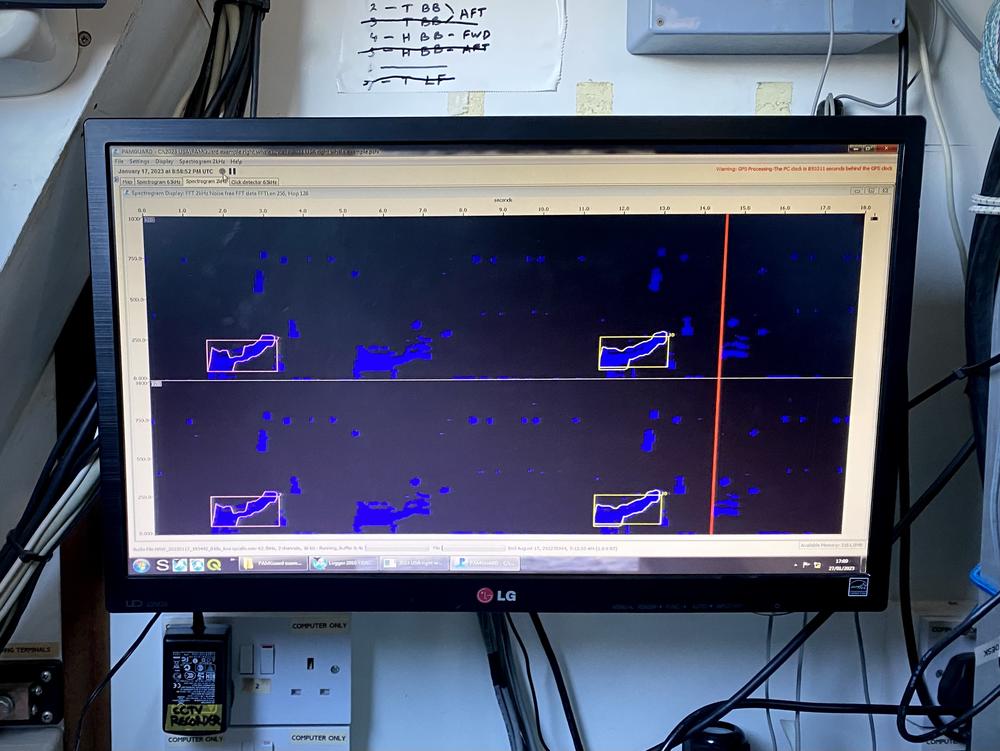

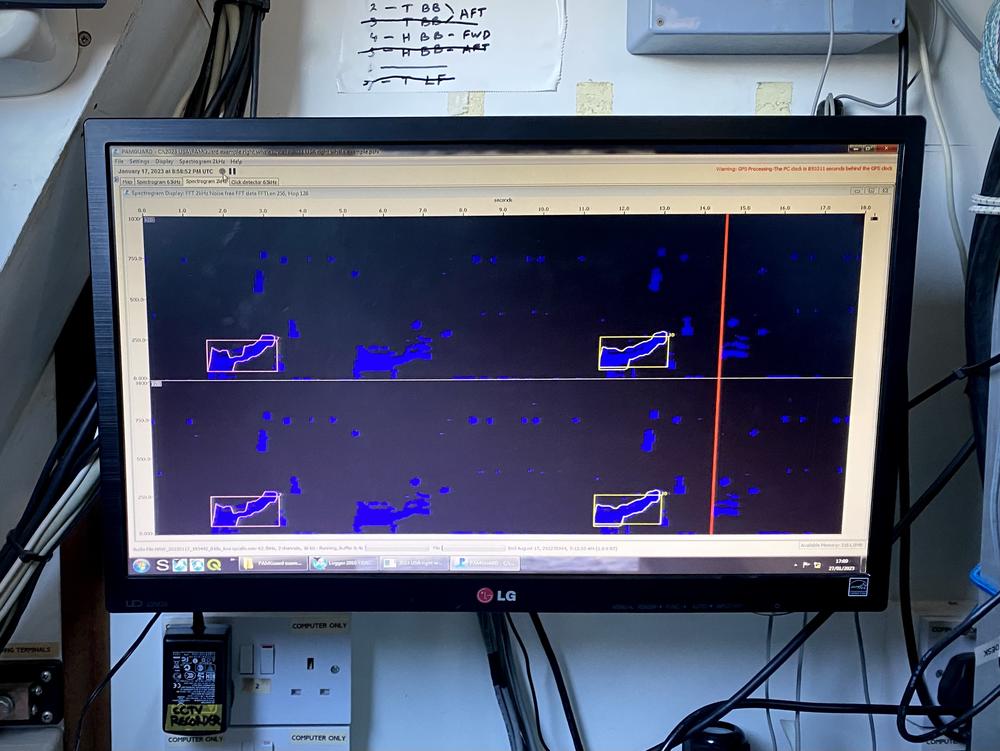

Caption

A computer visualization known as a spectrogram shows North Atlantic Right Whale calls, as recorded by the ship's hydrophones.

Credit: Benjamin Payne / GPB News

LISTEN: Crewmembers opened their floating research station to the public on Friday along Savannah's riverfront. GPB's Benjamin Payne reports.

——

With a decadent, three-story riverboat docked along the shore of the Savannah River, it would have been easy to miss the sailboat sitting nearby, were it not for its name: Song of the Whale.

Below the deck, it quickly becomes apparent that the vessel lives up to its name: an otherworldly voice reverberates throughout the cabin.

It's the call of a critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, as recorded about 10 days prior near Fernandina Beach, Florida, on one of the ship's underwater microphones, known as a hydrophone.

Anyone lucky enough to have been ambling down Savannah's riverfront on Friday had the rare opportunity to hop aboard what the International Fund for Animal Welfare calls one of the quietest marine research vessels in the world.

“Our work here has been primarily with the mothers and calves, trying to record them and trying to implement findings into some of the early warning systems,” senior research scientist Oliver Boisseau said. “The whales produce very distinctive, idiosyncratic calls. If these are detected, the Coast Guard is alerted, and then the Coast Guard can, in turn, alert passing vessels.”

North Atlantic right whales are “notoriously slow swimmers,” according to IFAW, which commissioned Song of the Whale in 2002. If ships can be alerted to a whale's presence early enough to slow down, that can give the creatures enough time to avoid a fatal collision.

Vessel strikes are just one of many existential threats facing the species, which also include entanglements with fishing lines and ocean noise pollution.

But this floating research station — which is operated by the U.K.-based nonprofit Marine Conservation Research International — emits almost no noise pollution by relying primarily on its sails to get around. When an extra push is needed, a five-bladed propeller similar to that of a stealth submarine helps it remain undetectable to the understandably skittish species.

A computer visualization known as a spectrogram shows North Atlantic Right Whale calls, as recorded by the ship's hydrophones.

“They used to span the entire North Atlantic,” Boisseau said. “They were found over in the U.K., which is where this vessel sailed over from in December. But unfortunately, their range — through commercial whaling — was restricted to just the Eastern seaboard of the [United] States and Canada.”

In addition to gathering acoustic recordings through hydrophones, researchers use cameras to identify individual whales, which each have unique patterns on their heads thanks to calcified skin patches known as callosities.

“I'm always very much in awe when we actually see a whale,” crewmember Judith Matz said. “So, my favorite part is seeing whales. But it's also the kind of dynamics that develop between the different people, because we constantly have new people on board. We have local visiting scientists. It's great to see how we can work together. I love those moments.”

The crew will follow the roughly one dozen calves and their mothers for the next several months, finishing at their feeding grounds off the coast of Canada in August.