Section Branding

Header Content

Activist Alice Wong reflects on 'The Year of the Tiger' and her hopes for 2023

Primary Content

For many Asian and Asian American communities, the Lunar New Year, celebrated in late January this year, represents a chance to start anew. It also comes with it a new zodiac animal: 2022 was the Year of the Tiger. In 2023, the baton passed to the rabbit — or for those in the Vietnamese community – the cat, a symbol of luck.

But, so far, this year hasn't felt so lucky. In the first three days, there were two mass shootings that directly impacted Asian American communities in California. Several days later, a video showing footage of Memphis police officers beating a Black man, Tyre Nichols, to death, was made public — reigniting calls for police reforms and further scrutiny of specialized police units. All the while, the Biden Administration is preparing to loosen more precautions around the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected older adults, communities of color and people with chronic illnesses or disabilities.

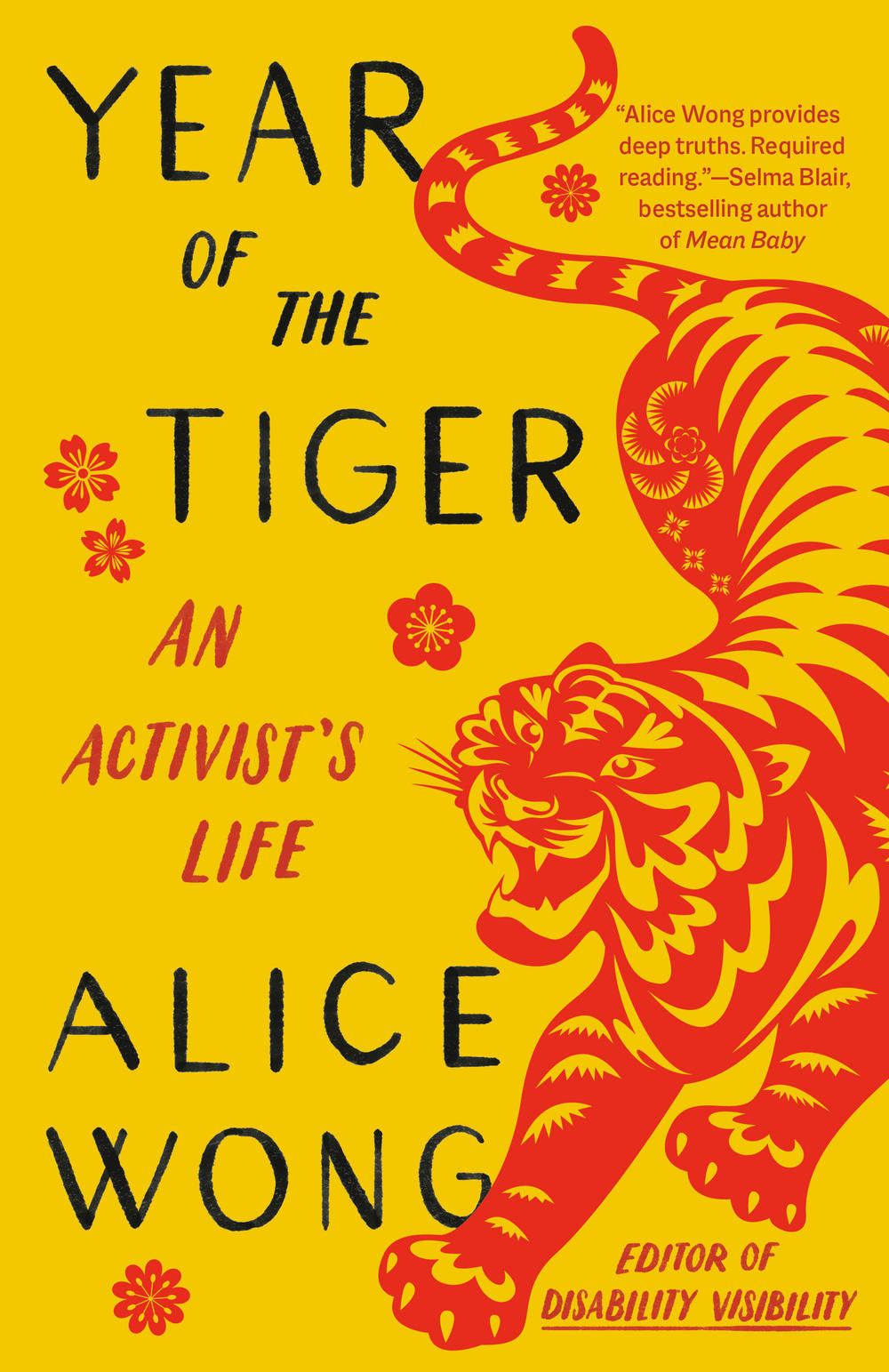

So NPR reached out to activist and writer Alice Wong, author of Year of the Tiger: An Activist's Life, for her thoughts on the start of the lunar year — and her hopes for the rest of 2023.

Born in the suburbs of Indianapolis, Ind, to Chinese immigrants, Wong entered the world in the Year of the Tiger, 1974. Along with the characteristics of the tiger zodiac — confidence, ambition and strength — Wong's body also contained a mutated gene causing a progressive neuromuscular disease that slowly weakens her muscles. The doctors told her parents that she wouldn't live to the age of 18 — Wong is now 48.

Today she is a self-described "disabled cyborg," as she writes in her 2022 memoir, a person "tethered to equipment, technology and electricity to keep [her] alive." And after a series of medical emergencies this past summer, Wong now communicates through a text-to-speech device.

Wong is best known for her activism and as the founder of the Disability Visibility Project. Her work focuses on amplifying the voices of disabled people and disability culture, and dismantling systemic ableism in the United States.

People with disabilities have often had to fight – and still do – to get the care that they need, working against systems that have often devalued their lives. In California, where Wong lives, the initial rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine, for example, went against CDC guidelines and prioritized age instead of underlying medical conditions.

"I realized in 2020 that the time to tell my story was now or never. That's what being a high-risk ventilator user who was deprioritized by the State of California for life-saving [COVID-19] vaccines will do to you," she writes of her decision to publish her 2022 memoir.

In the Year of the Tiger, Wong shares pieces of her story through a collection of essays, interviews, photos, and illustrations. And, perhaps through these glimpses of her life, Wong is demonstrating the most influential act of activism – living an unapologetic, unabashed disabled life filled with science-fiction, good food, and cats.

Interview questions were sent to Alice Wong, and her responses were recorded with the help of her text-to-speech device. The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Tell me about yourself! How do you like to introduce yourself?

I'm an Asian American disabled cyborg, a person that is tethered to equipment, technology, and electricity to keep me alive such as a ventilator and feeding tube. I'm also a writer, editor, and founder of the Disability Visibility Project, whose mission is to amplify disability media and culture. I love to mess around, collaborate with cool folks, and create trouble.

This past summer, summer of 2022, you had a series of medical emergencies — which has led to you using a text-to-speech app to communicate. How has this changed the way you view yourself and how you navigate this world — or how the world has perceived you?

My life has changed a lot since last summer, since I lost my ability to speak and eat. Just as I am very Asian I am very disabled now with a new body that has even more significant needs. I'm not sure how people perceive me now but I feel that there is a greater social and physical distance with others, especially non-disabled people. The challenges and barriers I face have increased but much of that is due to structural ableism and the way our world centers hyper productivity, white supremacy, and capitalism.

Alice, you're the author of Year Of The Tiger: An Activist's Life. You proposed this memoir in 2020 and wrote it during the COVID-19 pandemic – just in time to coincide with the 2022 Lunar New Year, the Year of the Tiger. Why was it important to you to write a memoir now?

A lot of my disabled friends and I feel our mortality intensely. Many middle-aged disabled people are considered elders in our community because of preventable deaths and marginalization. There are too many of us who should be alive today, if they weren't forced to live in poverty to keep their benefits, institutionalized or incarcerated in prisons and psychiatric facilities. Imagine a world if everyone had food, housing, healthcare, and freedom. This is what drives much of what I do, letting people know that another way is possible.

I was never supposed to live past 30 much less 40 and when I thought about the follow-up to my anthology, Disability Visibility, which came out in 2020, I wanted to do something creative, fun, and challenging. I'm much more comfortable amplifying the work of disabled people – and taking a look back at my life would be an opportunity to reexamine my work in a new context. One night in bed as I was dreaming up this book proposal and knowing how long it takes to get a book from manuscript to publication, I realized 2022 is my year and the title captures the ferocious cat vibes I wanted to share with the public. I wrote this memoir as a way to document my life in case I die, which I almost did multiple times last summer, so I can leave something behind as a disabled ancestor for future generations. And since this Lunar New Year is the year of the cat according to Vietnamese folks, I'll also claim this to be my year because I have lots of dreams and plans ahead.

Your dedication page reads "For the disabled oracles out of time; I join you in the chorus of our wisdom." Could you tell me about this dedication? Who are the "disabled oracles out of time"?

Like many people excluded and devalued in society, disabled people have been speaking truths that most people do not want to hear. I have many friends who should be alive today and their wisdom guides me to this day. Since the beginning of the pandemic, disabled people already were adept at life in isolation, mask-wearing, and organizing online. Non-disabled people who suddenly discovered online events and working from home did not acknowledge the decades of advocacy by disabled people pushing for these things that were considered too expensive or unfeasible pre-pandemic. Right now, disabled people have been vocal about the consequences of "return to normal" where getting infected is considered an inevitability or a minor cold.

Chronically ill people foretold the gaslighting and skepticism of long COVID and how denialists and misinformation will harm people who need care now [...] My work is part of a larger collective body of wisdom by disabled people from the past, present, and future. Some of us may be out of time but we are immortal.

Alice, I wanted to say thank you. Your description of Riley Hospital for Children and how it was a place where you felt like you belonged in a very weird way really resonated with me. When I was a child, I was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and the Children's Hospital in Atlanta was a place I felt most at home. I still find hospitals oddly calming to this day. I haven't shared this with many people because I thought it was such a fringe idea – to feel comfortable in a place often associated with death and mortality. So, thank you for helping me feel not alone.

Oh wow, I am touched that it resonated with you, Thomas. When I wrote that particular chapter, I didn't realize how much medical trauma I endured and how it's intertwined with joy and care. Our society has an aversion to death, aging, suffering, sickness, and disability. What if we acknowledge them as natural parts of the human experience rather than something to be eliminated or avoided at all costs? Life is not binary: healthy or unhealthy, disabled or nondisabled, low or high quality. We can and should embrace vulnerability and interdependence and not see them as weaknesses.

The other day Zeke Emanuel, a doctor and bioethicist, tweeted that living too long can be debilitating and that people over 75 have ineffectual and feeble lives. Eugenic attitudes like his demonstrate how some people are valued more than others. Disabled and chronically ill people constantly push back against these narratives having to defend their right to exist. Productivity does not make a person inherently valuable. Everyone is valuable.

Year of the Tiger isn't structured like a traditional memoir – telling the story of your life in a chronological order. Rather, it's a collection of essays, of interviews, of art and comics. There's a playfulness – and dare I say, shade – to your memoir. When I was reading it, it reminded me of a scrapbook or a time capsule – almost like rummaging through a forgotten shoe box of pictures, memories, and ticket stubs. What was it like gathering and collecting all of these memories and experiences? What was going through your mind?

In the introduction of my book, I question the assumptions of what makes a good memoir, and I was intentional about subverting the form and making it my own [...] Following the adage show not tell, I had preferred to show people parts of my life rather than pontificating about it. I could have written several chapters of my time as a teenager but instead I included my high school transcript which showed my mediocre, non-model minority grades and my super-cringey poetry. The mixed media such as photos and graphics in between the chapters add some fun for the reader. I included a crossword and Chinese homework inviting the reader to interact and play with the material. Gathering bits of stuff and putting them together in a collage was similar to my experiences as an editor, curating separate pieces to tell a larger story. I truly enjoyed going through my things because I am all about the 80s and 90s. And yes, like a mushroom, I live for shade and there's a lot of it in the book.

Your memoir made me feel seen – with your love of cats and food and sci-fi, nerd references. X-MEN! Charmed! Star Trek! Are you watching anything fun lately? And – the more hard hitting question – why nerdom and sci-fi? What about this genre appeals to you?

Many people know me for my work as an activist but I wanted to make sure I share my pleasures and joys. Speculative fiction resonates deeply with people who feel different, the other, alien. As a kid who didn't play sports or an instrument, books were liberatory. I could fly far beyond this universe by reading. The library was my safe space where my imagination could go wild. Speculative fiction is often political with social commentary and that's another reason why I gravitated toward it. I love The Bad Batch, a Star Wars series on Disney Plus, about a group of clones that are actually all disabled since they are considered defective. I'm enjoying The Last of Us on HBO Max, an adaptation of a game about a post-apocalyptic world where humans have become infected by a mutated fungus. As a diehard Star Trek fan, I cannot wait for the third season of Picard on Paramount+ that will include many characters from Star Trek the Next Generation. Even though you didn't ask, I'm gonna say Deep Space Nine is the best Star Trek show. Yeah, I said it.

It's clear you take pride in the work that you've done. But you've also hinted at almost a hesitancy in being forced into this life of activism. Do you have any regrets with the path you've chosen and the experiences you've lived?

I have experienced a lot of ambivalence and precarity in my life. I question the limits and values of being proud when it can be considered compulsory and performative. It took me a long time to even identify as an activist even though I've been one by default. I truly believe I had no choice [but] to advocate for myself ever since I was a child because it was a matter of survival in this unforgiving and inaccessible world. And that's what burns my biscuits, you know? Everything I've done in the past led me to where I am now and I don't regret any of it. However, I resent the fact [of] how hard I have to fight to claim space for myself. In the future, I don't want any disabled person to have to hustle and fight so hard just to get their basic needs met. We all deserve more and perhaps that is one takeaway from my book.

The last section of your memoir is titled "Future." Unlike much of the book, the chapters are more explicitly projecting into the future — while also honoring the past and legacies of disabled ancestors. There's a wish list of things you want to see happen. What's next on your to-do list?

I am working on several secret projects, I have a few wild dreams I would love to manifest and speak into existence. I would like to see my book adapted into a film or television series. I would like to be a model. By the way, I joke with my sisters that Gucci Valentino would be my drag name because I love those two brands. I would like to be the editor in chief of an imprint at a major publisher focused on books by disabled writers. I would like to produce and write an animated series. I would love to have a cameo in any Star Trek show. I want to do a collab with Funko for a series of pop culture collectibles featuring disabled comic book characters. And, last but not least, I would also like to have a syndicated show or podcast on NPR called Disability Visibility since radio has a big time diversity problem. To the stars Thomas, to the stars!!

In this "Future" section, there's an interview where age 6 Alice talks to age 48 Alice and age 48 Alice talks to age 96 Alice. So, my question to you is, how do you see the world changing in the next 5, 10, 20 years? What do you want to leave behind when you're gone?

Things are a big dumpster fire right now with the climate crisis, police brutality, mass death from COVID and millions of people with new disabilities from long COVID. Everything is overwhelming and bleak but there's also immense beauty and love everywhere amongst us. All you have to do is look. Change is hard and takes a very long time so I'm not sure what the world will look like in the future but I have hope that we will keep each other safe and that we will show up for each other. I want to leave behind a body of work that is in community with others and, most importantly, relationships and good memories that will live on forever.

As you know, the 2023 Lunar New Year is upon us, marking the end of the Year of the Tiger. The baton has been passed on to the rabbit – or if you're Vietnamese like me — the cat, a symbol of luck. There's something poetic about this transition. The tiger – a confident, ferocious, and passionate feline – has cycled through to the cat – smaller, but just as confident, ferocious, and passionate. What do you hope will be in store for this new year?

My heart is filled with gratitude and joy for being alive in this moment. This Lunar New Year has been horrific with the mass shootings in Half Moon Bay and Monterey Park. Thoughts and prayers are not enough but I am holding space for everyone traumatized and harmed. Tyre Nichols and so many other Black people should be alive and abolition is the only way forward, not reforms, platitudes, or half measures. We have to fight the forces that dehumanize and erase us. And we must be in solidarity with one other to make that happen. I hope and want a world filled with justice where everyone is safe and valued.

Meghan Collins Sullivan edited this interview.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.