Section Branding

Header Content

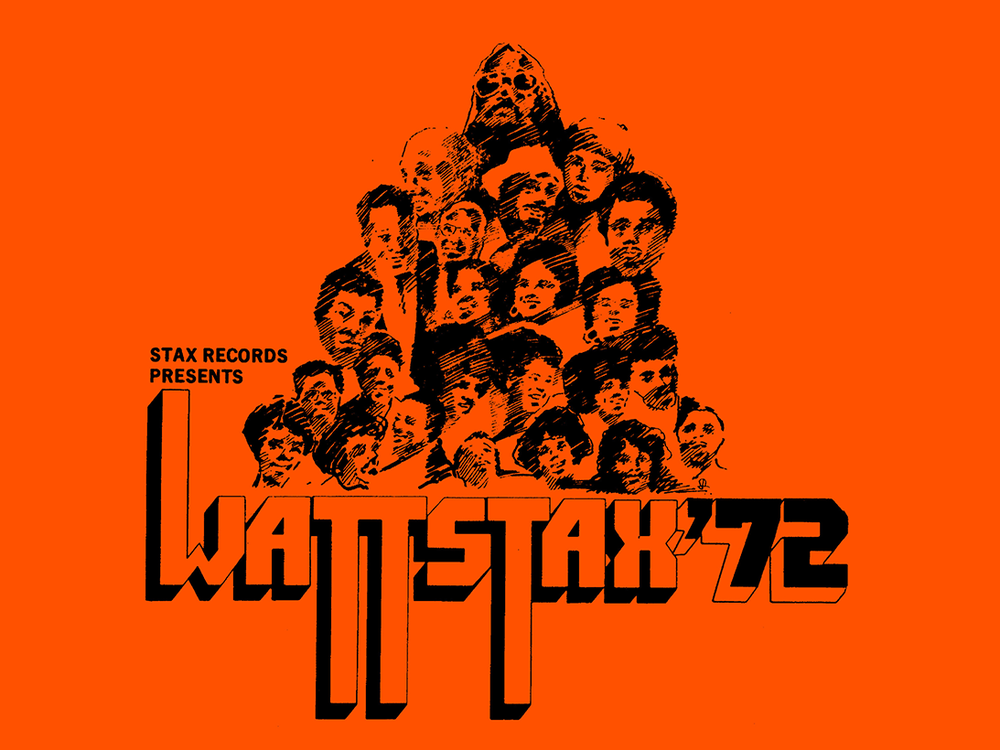

50 years later, the celebrations and contradictions of 'Wattstax' still resonate

Primary Content

Time capsules are funny things. They preserve a moment, a still shot of a time and place. We, the future, look at it and think we know not just that one moment, but everything that lives along the edges, outside the frame. It's wishful thinking, of course. One snapshot, one item, can hardly tell us everything we need to know about all of the names, faces, sounds that make up history. But there are some projects that try to, projects that try to give their time a shape, make it three-dimensional, and make it easier for the future to understand it.

This year, on the 50th anniversary of its 1973 release, the film Wattstax will be returning to theaters again. The documentary, itself a time capsule of a city in flux, captures the Watts Summer Festival concert hosted by Stax Records at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on Aug. 20, 1972. It will be joined by several albums' worth of music from and surrounding the event, packaged together as Soul'd Out: The Complete Wattstax Collection. And while the music and the film are great opportunities to revisit a moment, this re-release is also a chance to reflect on the edges, the things that lay beyond the frame, to understand why the music, the film and the moment they captured still resonate so strongly.

While Wattstax is probably the most well-known of the Watts Summer Festival events, it wasn't the first. That distinction belongs to the 1966 festival. And while it was generally remembered as a beautiful event, the need for it came from something much uglier: the arrest of Marquette Frye in 1965, which sparked the Watts Rebellion. The stories of the initial incident diverge, but by the end of it Marquette, his stepbrother, Ronald, and his mother, Rena, had all been arrested. The police said they were resisting as police tried to arrest Marquette for drunk driving. The Fryes and many onlookers said it was a clear case of police brutality, as all three suffered injuries.

The August heat combined with years of neglect and abuse into a night of violence. Rocks, fists, bottles, nightsticks. The Watts Rebellion lasted six days, and resulted in 34 deaths, 1,032 injuries and 4,000 arrests. The next year, organizers established the Watts Summer Festival, an event they hoped signaled acknowledgement but also the process of moving forward.

***

The fires were out but the emotions were still smoldering when Stax Records, a Memphis-based soul label, opened a Los Angeles satellite office in 1972. Stax's then-owner, Al Bell, had been monitoring the progress, or lack thereof, in Watts since the Rebellion. "By our estimation, the residents of Watts had lost all hope," Bell writes in Soul'd Out's liner notes. "I knew we had to do something to change this and I was certain that we could bring healing through the power of music."

The idea hadn't come completely out of the blue. Music had been used as a source of healing in the community since the year after the Rebellion, when artists like Les McCann and Hugh Massakela performed as part of the Watts Summer Festival's inaugural year. Over the next six years, the festival continued to grow, as did the number of musical acts: Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Fela Kuti, Nancy Wilson, Roberta Flack. The festival was a chance to commemorate the events of 1965, to mourn what was lost, but also to celebrate what remained. Bell also saw the opportunity to partner with the festival as a chance to achieve some of his West Coast goals; in opening the label's LA office, he had also been hoping to pursue partnerships with TV and film companies. With this event, he could promote his artists, produce a documentary of the event and, as Rob Bowman, author of Soulsville U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records, writes in the liner notes, "provide support and social uplift for the still badly hurting Watts community."

Like prior Watts Summer Festivals, Bell wanted to use art as an activist tool. Not just as a way to organize, but as a way to see the beauty in Blackness, the gifts, the community. At this festival, people would find "refuge in the spirit of celebration," Bell writes. This was a difficult line to walk, and hinted at a complication that had existed since the beginning of the festival. Though the festival was started, in part, to soothe tensions, many activists saw the Rebellion as the first shot of a revolution. To them, the idea of a festival, with its lights and music rather than change and action, seemed like silencing the voices the Rebellion had finally made audible.

Still, maybe Bell saw the 1972 festival as a chance to bridge the gap: a chance for the label to be all things — at least for one night. It would be art and activism. Community and capitalism. A mirror for the Black community and a window for those outside of it. The official theme for Wattstax was The Living Word, a Biblical reference to the way that God's message was alive in the actions of the people. But in this case, that word was soul. And it was alive in each and every cascading shade of brown skin, in every hip sway, in every downbeat, in every raised fist and perfectly-shaped natural.

The company already had a slate of performers who were well-versed in songs that veered into the political. The Staple Singers had long been infusing the spirit of change, both secular and religious, in their music. Otis Redding had put his spin on the Sam Cooke-penned protest anthem "A Change Is Gonna Come." And through the label's Chalice imprint, gospel artists released poignant songs like "The Assassination" and "Our Freedom Song." Politics didn't come to the music; it was already there. There was almost no way that the concert wouldn't be viewed as political. What may have been in question is how radical those politics were.

***

One of the most striking things in listening to the entirety of the re-issued music is its length. Wattstax was planned as a six-plus-hour concert, and as each song fades into another, or is broken up by speeches from the notables like Jesse Jackson and Melvin Van Peebles, the enormity of the live event really comes into focus. Bringing together all this music was a huge undertaking. But it was only part of the story: The whole thing was being filmed, and Bell had big plans for it.

Concert documentaries weren't new, but Wattstax director Mel Stuart said he found the slate of them released prior to the concert — Monterey Pop (1968) Woodstock (1970) and Soul to Soul (1971) — lacking. They were like newsreels, Stuart said, and he didn't do newsreels — instead, he wanted the music in his film to serve as "a springboard into a camera exploration of a segment of the Black Experience."

Stuart wove street scenes and interviews with locals in with the concert footage, creating something that worked as both a musical performance and a political documentary. There's a moment, for example, when interviewees are asked when they knew they were Black as Kim Weston's rendition of "The Star Spangled Banner" plays underneath. The answers are often painful, but their vulnerability is an indictment. This awareness points a finger at a country that drains childhood and innocence from Black kids, while simultaneously trying to hide this reality away from everyone else. Later, Richard Pryor, also a Stax artist, asks why there are laws for pedestrians but not for when cops "'accidentally' shoot people." There's a heaviness in the laughter, rooted too much in truth.

Politics was an important part of the event, but Stax was still a business. Bell acknowledges this in one of the liner notes essays, saying the festival "was designed to aid in [increasing] the visibility of Black culture, but it was also designed as a PR tool for Stax and its artists." All the Stax artists — from familiar names like Rufus Thomas, Johnnie Taylor and Kim Weston to on-the-rise or newer artists like Frederick Knight, Eric Mercury and The Temprees — were going to perform for a crowd of over 100,000 people, an undeniably huge PR move. Each person in the audience represented a potential change-maker, sure, but they also represented a potential consumer.

One of the primary sponsors for the event was Schlitz Brewing Company, and listening to the recordings, there's never a chance to forget it. While the partnership allowed them to charge just a dollar for tickets, culture and commerce clash in the many overly-long shout-outs to the company. It's more than a little jarring to hear Rev. Jackson extol the virtues of Schlitz in the same tone as a Sunday sermon as he announces a partnership between Operation PUSH and the brewery. The crowd doesn't seem convinced either. It's not hard to see why some activists of the time saw Watts Summer Festival events as stifling real change.

Despite that, many of the performers seemed to see their performances as a chance to affirm the audience and themselves. The Staple Singers tell us "I Like the Things About Me," with Pops' guitar punctuating this smooth declaration of pride ("I like the things about me I once despised"). The Soul Children sing "I Don't Know What This World is Coming To," a country-fied, gospel-influenced plea for change and unity. Rance Allen soulfully screams "Lying on the Truth," an accusation, an acknowledgment, but also a way forward. And Kim Weston asks us to "Lift Every Voice and Sing." This was a moment of freedom, of pride. Stax artist Lee Sain called the event "a spiritual revolution." And you can hear it in the music. Schlitz fades. Even Stax fades in a way. All that's left is the music and the intensity of 100,000 people, who all at once, know they are beautiful.

***

Opening this time capsule today, Wattstax fits as much in its own time as it does in ours. It isn't just about the music. Though the music — from the winding funk-rock of the Bar-Kays to Deborah Manning taking us to church with "Precious Lord, Take My Hand," to a beautifully over-the-top Isaac Hayes — is fantastic. And it isn't just about the politics, even as Black Los Angeles residents debate their conditions and the crowd chants "I am somebody" in a way that feels both proud and defiant, daring someone to disagree. It's about a city that burned in 1965. A hero murdered in 1968. A people still fighting for dignity as they dance cool streaks across an August afternoon. It is about all of those at once.

In Bowman's liner notes essay, he describes the first time Stax artist Carla Thomas visited Los Angeles. It was just a few days before the Rebellion. She'd been asked to come to Watts by a friend of a friend, to take a tour and see the neighborhood: "I was in the middle of something that I didn't even know existed. ... You would think I was in Alabama or Mississippi." Just out of the frame of this image is a truth — Watts isn't unique. Neither is Alabama or Mississippi or Florida or Massachusetts. They are all a part of the same system, and Bell understood that. As he told Jet Magazine in a 1971 interview, "A company involved in Black music must be a part of the Black community. We must know where the Black community is at, where it's going, and where it's going to be." It was business, sure. Activism and commerce are different things, and no one is buying their way to equality. But what did it mean for someone in Birmingham to see someone in Watts and understand them? What did it mean to have your anger, your beauty, your humor, your frustrations be broadcast on screens across the country?

There is power in validation.

And as we sit here 50 years later, there is still that need for validation. When lights from a police car flash, and muscles tighten, waiting. When it's hard to keep track of the deaths and hashtags, the names bleeding into one another. When conversations from 1972 feel like they could be had today. It's the validation that lives outside the frame, the understanding, the knowledge you aren't alone. Wattstax was a community built on music.

The film opens with Pryor sitting alone against a solid black background. "All of us have something to say," he says, eyes focused directly on the viewer. "But some are never heard." They were finally heard, he explains, seven years ago through the Rebellion, and heard once again at Wattstax as they "felt, sang, danced, and shouted the living word in a soulful expression of the Black experience." Ultimately, even with all of the history bearing down on that moment, Wattstax was a chance to be heard: "This is a film of that experience," Pryor says. "And what some of the people have to say."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.