Caption

Myrick Marine positioned a barge off Twin Palms to haul debris off the island. The cleanup will cost taxpayers $35,000.

Credit: Georgia Department of Natural Resources

Bill Sharpley has been camping on Twin Palms since his now 30-year-old daughter was in diapers.

“It’s where you get to hang out with your kids, sometimes without the moms involved and do stuff that the moms wouldn’t let happen, like going off the swing too early, or going across the (rope) bridge,” he said. “You teach them how to drive the boat, you teach them how to fish, teach them how to shoot guns. It’s just everything you can imagine you want to do with your kids.”

Myrick Marine positioned a barge off Twin Palms to haul debris off the island. The cleanup will cost taxpayers $35,000.

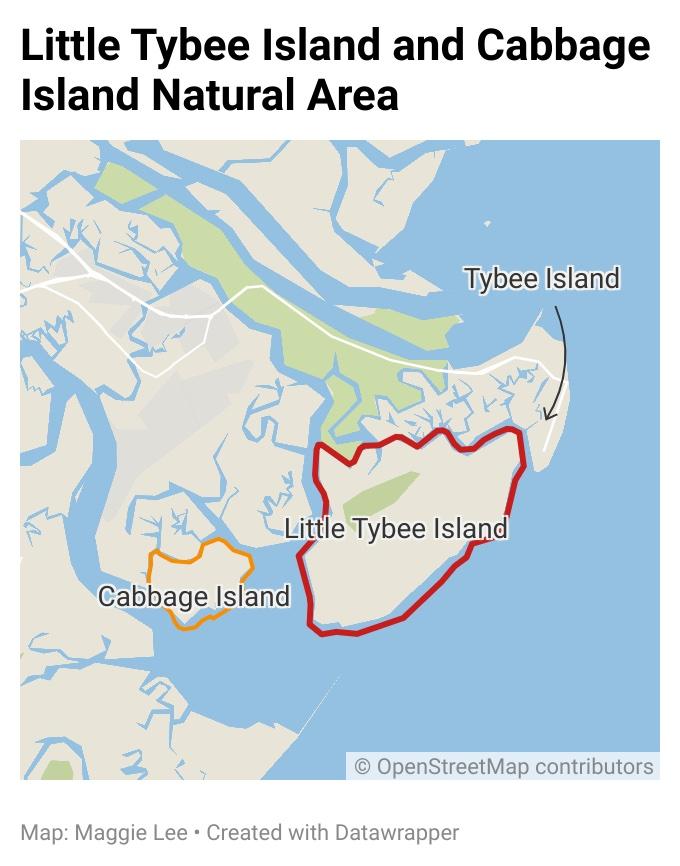

The beach-fronted, forested island forms part of the 7,700-acre Little Tybee and Cabbage Islands Natural Area, a state Heritage Preserve that sits right next door to Tybee. With access only by boat, it’s long served as a nearby getaway for locals in the know like Sharpley.

But over the years, as the tradition on Twin Palms morphed into elaborate glamping in semi-permanent structures kitted out with the comforts of home, it’s sparked complaints from other visitors to the state-owned island where camping is supposed to “leave no trace.”

Sharpley is well placed to know the rules, even to enforce them. He’s a lieutenant with the Chatham County Police in its Marine Patrol Unit. He’s also 33-year veteran of the Savannah Police Department.

Instead of honoring DNR’s rules about buildings in the preserve, he’s been negotiating with the department by email for months, identifying himself as a frequent camper, but not as a law enforcement officer.

A fully stocked “kitchen” stood on Twin Palms in mid-January. Three tents had been set up behind it. The Georgia Department of Natural Resources hired a contractor to begin removing any remaining structures on Feb. 13.

Sharpley removed some debris over the last four months, but the DNR ultimately hired a contractor to clear the remaining structures and their contents. Myrick Marine hauled away debris at a cost of about $35,000 this week. And that’s only the first encampment. DNR employees got their first on-the-ground look at an even larger structure on the Long Island area of the preserve on Tuesday.

Little Tybee is protected now, but its history includes close calls with industry and housing.

In the late 1950s, the Georgia State Highway Department considered building a bridge to the island to facilitate development. When that plan failed the land was sold to a phosphate mining company. The threat of phosphate mining created a public outcry that helped lead to the Coastal Marshland Protection Act of 1970, a law widely credited with keeping Georgia’s salt marshes intact and functioning.

Chatham County's coast is seen: Northernmost is Tybee Island, below it is Little Tybee, then southwest is Cabbage Island. Little Tybee and Cabbage Islands Natural Area form a state Heritage Preserve at the north end of the Georgia coast.

Mining company Kerr-McGee donated the island to The Nature Conservancy. In 1991, the conservation group sold the land to the State of Georgia for the cut-rate price of $1.5 million but retained a perpetual easement. Gov. Zell Miller dedicated the islands as a Heritage Preserve in 1992, stipulating that Little Tybee and Cabbage Islands shall be used for “recreational, educational, scientific, and cultural research purposes, as well as environmentally sound preservation and management of the island ecosystems.” Hunting is not allowed.

The name “Little Tybee” is a misnomer. Its area is triple the size of Tybee. DNR estimates it includes more than 5 miles of beach. Most of the upland is less than 10 feet above sea level and covered in maritime forests with its typical live oaks, slash pines, palmettos and yaupon holly. Most of the 7,700 acres of preserve, however, is salt marsh.

The preserve provides important habitat for birds, including some rare species. Federally threatened piping plovers regularly make use of Little Tybee. Bald eagles nest in its tall pines. Peregrine falcons feed and roost there. Whimbrels, a type of shorebird, rest on the island in groups of up to 2,000 birds during their long distance migration from South America to the Arctic. American oystercatchers, Wilson’s plovers, least terns, gull-billed terns and black skimmers all nest on Little Tybee’s beaches.

Little Tybee’s Heritage Preserve designation offers it the state’s highest level of protection. That’s important for scientific research on the island. In recent years DNR ornithologists have studied the preserve’s abundant horseshoe crab spawning that attracts large spring flocks in Georgia of federally threatened red knots, a long distance migrant considered a flagship species for shorebird conservation. The Georgia Sea Turtle Cooperative monitors Little Tybee beaches each summer for loggerhead sea turtle nests, protecting them as needed.

Jason Lee, a program manager with the DNR’s Wildlife Conservation Section, began putting a plan in place to remove the encampments on Twin Palms late last year.

A rope swing at Twin Palms.

Among those who have made the DNR aware of the encampments over the years is a boater who frequents the area. The Current has agreed to withhold his identity to protect him from retaliation.

He first noticed a large encampment on Twin Palms nearly 10 years ago, he said. It wasn’t visible from the water, but he’s a rare plant aficionado and likes to poke around for them on barrier islands. Instead of rare plants, one day he found an empty “tent city.”

“There was no one there,” he said in a telephone interview with The Current. “Luckily, I mean, I don’t know what happens when you run into a community like that.”

There was also a ropes course through the trees but “very few” permanent structures then.

He notified DNR at the time but was told the department didn’t have enough of a presence in Savannah area to police the situation.

From aerial photos DNR became aware of sizable structures on Twin Palms and other parts of Little Tybee, visible from overhead. Lee indicated he was trying to address the issue through public outreach and education, but the problem has only worsened.

“We are aware of the structures, and though it has taken some time, are currently working on a solution,” he wrote in 2021. By fall 2022 a plan was taking shape to hire a contractor to remove the structures, equipment and litter, but the camps remained.

Utensils stand at the ready in mid-January at an illegal encampment on Twin Palms.

Sharpley learned of the plans and in October emailed Lee from a private account to tout the campers’ own cleanup efforts. He signed his email “Bill,” and indicated he was one of the campers, but didn’t identify himself as a Chatham Marine Patrol officer.

The Current reached Sharpley through email and he replied by phone with his camping friend Bobby Boyd also on the line. Sharpley did not want to be identified. “I’d really rather not give you my last name just because of my job and my position,” he said. But after a cross check of his email address and phone made it clear who he was, he verified he was with the Chatham Marine Patrol.

“Having become aware of the issues regarding Twin Palms, a group of concerned citizens took needed action to help preserve the island,” he wrote in October. “Please find the documented improvements to Twin Palms below.”

He included photos and a list of items removed: 14 bags of trash, two wheelbarrows, pots and pans, a full size queen metal bed frame, six full tents with contents, blankets, air mattresses, clothing, old tent poles, two full size grills and one metal smoker, a large tan tote, and a large foam mattress.

In mid-January, about a half-dozen tents, some with blankets and sleeping bags, were set up around Twin Palms.

Lee responded, warning that changes were coming. “(O)ver the years there have also been many complaints of campers feeling or being threatened by other campers, which has led to more public requests to have a reservation system with enforcement.”

Sharpley wrote that he wasn’t aware of any threats: “I know some pretty seedy folks used to come around but that doesn’t happen anymore. There are less campers than years past and it’s more of a family environment. I literally have seen priests on the island.”

Campers left a knife embedded in a tree on Twin Palms in January.

On Oct. 28 Lee wrote back announcing “DNR is issuing notice that a Little Tybee cleanup will begin in 90 days. Any structures will be included in this effort.”

In several rounds of correspondence, Sharpley reported more trash and tent removal, but also argued for keeping the “kitchen” shelter as protection from lightning.

“The structure currently on the island are well built and provided a safe place for visitors to the island during storms,” he wrote.

In early January, Sharpley, again using only his first name, wrote to The Nature Conservancy, arguing that the use of heavy equipment to remove structures on the island would cause more environmental harm than the structures themselves do.

He has suggested that DNR should focus on removing abandoned boats from area waterways rather than cleaning up Little Tybee.

His group wanted to “continue the rich family traditions of camping on Twin Palms which has lasted at least 4 decades.”

More recently he argued for keeping the ropes course.

“Why on earth would the Monkey Bridge need to come down,” he wrote last week, referring to the rope bridge. “I know it’s been there 25+ years. That’s just silly.”

For Lee and the Georgia DNR, it’s clear why the structures and the ropes course need to go. For one thing, the state could be held responsible if someone gets hurt.

The structures aren’t approved or inspected. DNR can’t ascertain their soundness, Lee said.

“You can see the obvious liability and danger there with an unmaintained ropes course on public property,” Lee said. “The buildings themselves, they’re wooden structures and you’re in a very dynamic environment with high winds, hurricanes regularly. And those structures are not something that we as an agency can allow to be used on public property.”

Even small structures can affect the way wildlife uses the island, said Rene Heidt, cofounder of the Tybee-based nature tour business Sundial Charters. She noticed a big difference after a small hut on the preserve burned down.

“The thing is all the birds have returned to that spot,” she said. “Now there’s always snowy egrets, great egrets, black-crowned night herons, little blues. The whole gamut. And they all hang out there.”

Several trees have been felled at the Twin Palms campsite on Little Tybee. As a nature preserve, the felling of even dead trees is forbidden.

Lee agrees that structures and wildlife don’t mix.

“Just by virtue of placing a structure anywhere within the maritime forest, you’re removing some of the habitat,” he said. ” And continued regular presence of humans and trash as we have had on Little Tybee will definitely both drive away and endanger wildlife.”

Island visitors have complained, Lee said.

“Campers, kayakers, hikers who show up on Little Tybee and expect to find a pristine environment, instead, find trash and structures,” he said. “So it does ruin the recreational potential and experience for other folks as well.”

Sharpley and his camping buddy Boyd say they haven’t had a problem with other campers. They recounted how another camper arrived at “their” spot with a group of 15-20 kids, but deferred to Sharpley’s group and moved to another site. And they’ve helped out visitors in distress, they said.

“We’ve rescued kayakers at night and brought them into the camp,” Sharpley said. “So they got food and water and a place to stay. So it’s not like a territorial thing. It’s more creatures of habit than anything else.”

But a recent 911 call shows just how intimidating some of the regular encampment users can be. Long distance kayaker Jonathan Dedic heard gunshots hitting the water around him him as he paddled past the island in early January. Fearing he was being shot at, he called 911 and paddled away from Twin Palms. The 911 operator eventually connected him to the Chatham Marine Patrol to file a report once he was safely back on land. The responding officer downplayed the possibility he had been a target.

“After speaking with the complainant it was brought up that it could have been target practice and they could have just not been conducting firearms safety effectively,” Officer Heath Wynn wrote. “There could also be hunters on the island.”

Hunting is not allowed at the Heritage Preserve, Lee said. Nor is discharging a firearm.

Sharpley’s friend Boyd said they used to pack everything in and out, leaving nothing on the island, but not lately.

“We call it camping, but for barrier island camping it’s pretty much glamping,” Boyd said. This past November their group reached 15-25 people, but in years past the head count approached about 200.

Sharpley and Boyd say they take advantage of the structures that were built by someone else. “We probably know who built them, but we didn’t do it,” Sharpley said.

A barge is loaded with dismantled structures removed from Twin Palms, and the work isn’t finished.

“Somebody built a kitchen-type area with some countertops and a tin roof over it,” Sharpley said. “And that’s, I think, part of what the DNR had wanted to get off. But we’re not the only ones that use that island. And a lot of people have been leaving air mattresses and grills and tents and stuff like that.”

Ultimately, Sharpley said he was glad the DNR and The Nature Conservancy got involved.

“Obviously, we’d like to see them leave the two kitchens that are there, but we don’t really have any control over that, ” Sharpley told The Current last month.

Lee said his department had no choice.

“We, DNR, are currently in violation of The Nature Conservancy’s conservation easement and of our obligations as a Heritage site, so we have elected to completely remove all illegal structures on Little Tybee,” Lee wrote in an email. “We both appreciate the public who frequent the Natural Area, have clearly heard their complaints of illegal activity that negatively affects the wilderness experience and the wildlife habitat.”

The DNR hired Myrick Marine Contracting to remove structures and debris. Over the course of Monday and Tuesday the company dismantled the remaining kitchen and loaded up a barge with debris. Total cost to the state so far: $35,000. And that’s likely to get bigger.

Twin Palms was first, but another large structure has been photographed by drone on Long Island. DNR is making plans to remove it as well, along with any other structures they find.

Two DNR employees who visited Long Island on Tuesday heard gunfire from a makeshift gun range as they approached. The men they encountered there said the nonprofit Tybee Marine Rescue Squadron built and uses the compound. DNR is working to verify who’s responsible for it so that state taxpayers don’t get stuck with that removal bill, too.

A Georgia Department of Natural Resources drone captured this image of an illegally built structure on Long Island in the Little Tybee and Cabbage Islands Natural Area. In mid-February 2023, DNR personnel examined the structure in person for the first time this week.

As for future camping on Little Tybee, DNR’s management plan calls for leave-no-trace camping only in designated areas that will soon be posted and require a Georgia Public Land Pass, which can be purchased online.

“If the island continues to be trashed we will institute a reservation system,” Lee said Wednesday. “I’m fond of it being one of a few places you can camp on the coast at will, but enough is enough.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.